Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

6 min read

A few weeks ago, we took my son to the zoo. At 16 months, we weren’t sure he quite understood what was happening, but we know he loves animals—or, at least, making animal noises—so we figured we’d give it a try. Soon after arriving, we approached our first large animal, an Andean Spectacled Bear1. It was beautiful, majestic even, its shiny black and brown fur glistening in the sun. It was sauntering across a small, enclosed area, adorned with a few trees and a dirty pool of stagnant water. I knelt down beside the stroller and pointed, with perhaps too much enthusiasm. Wow! Look at that! It’s a bear! Isn’t that cool?!

My son looked into the enclosure, pointed one chubby finger, and then looked back at me in wonder, his eyes wide. And in a voice of sheer reverence, as if he couldn’t believe his luck in having come across something so incredible, said: water!

The gift guides are coming

I’ve found myself reflecting on my son’s unbridled enthusiasm for stagnant zoo water as we enter the blazing firestorm that is the Internet holiday season. There are 30% off sales using code BLACKFRIDAY. There are gift guides (so many gift guides)2. There are ads for, in my case, cozy-looking athleisure pullovers in muted colors and gift boxes of bespoke chocolate macaroons3.

There are things. So many things. And as the month careens uncontrollably toward the new year, gathering speed as it goes, we will continue buying those things.

I’ll buy myself that pullover and, when I do, I’ll tell myself that it will be great. I’ll imagine how comfy it will be, how great it will look in all my Zoom calls, how the beige coloring will nicely offset my pale winter skin. And those first few times I wear it, I’ll be really happy! It will be comfy and Zoom-friendly!

But, as always, the excitement will fade. My pullover will no longer bring the joy it once did. It will take its place in my closet, amongst all the other things that once brought me so much joy, and now are just the standard accouterments of everyday life.

Why? Why does this happen? How can my son find such joy in dirty zoo water, while I keep chasing renewed joy with each Instagram ad?

Is there anything we can do about it?

The surprising science of hedonic adaptation

Imagine you were to win the lottery. You’d be pretty happy, right? Certainly happier than if you’d not won the lottery…right? In a classic 1978 study, researchers discovered that the answer is, actually, probably not.

They gathered a group of recent lottery winners, who’d scored anywhere from $50,000 to $1M, and asked them about their current levels of happiness. They also gathered a group of non-lottery-winners and compared their happiness ratings. What did they find? No difference. Even winning the lottery—an event some argue to be even better than buying a new pullover off Instagram—doesn’t seem to bring the lasting happiness we’d envision.

This phenomenon, of adjusting our emotional responses to events over time, is called hedonic adaptation. The premise is simple: we adapt to things way faster and more easily than we’d expect. This happens for good things—like lottery wins and holiday purchases—but also bad. In the same 1978 study, the researchers also interviewed individuals who’d recently had a catastrophic accident that resulted in paraplegia or quadriplegia. What happened when they asked these individuals to rate their everyday levels of happiness? Again: no difference from the controls.4

This is sometimes called the hedonic treadmill. No matter how fast we run, we always stay in place, just as we always return to baseline after a spike (or dip) in happiness. And because of how terrible we humans are at affective forecasting—that is, predicting how we’ll actually feel about a positive or negative event—it’s a lesson we never learn.

Due to errors in affective forecasting, when we add those cozy, sheepskin slippers to our online shopping carts, we envision ourselves sitting in front of a roaring fireplace, holiday jazz filling the air, exquisitely happy as the slippers cocoon our once-frigid toes. But then we actually get the slippers and, over time, hedonic adaptation kicks in. Soon, we’re back to baseline, just as happy as we were before the purchase (though, with slightly warmer feet).

So what can we do about it?

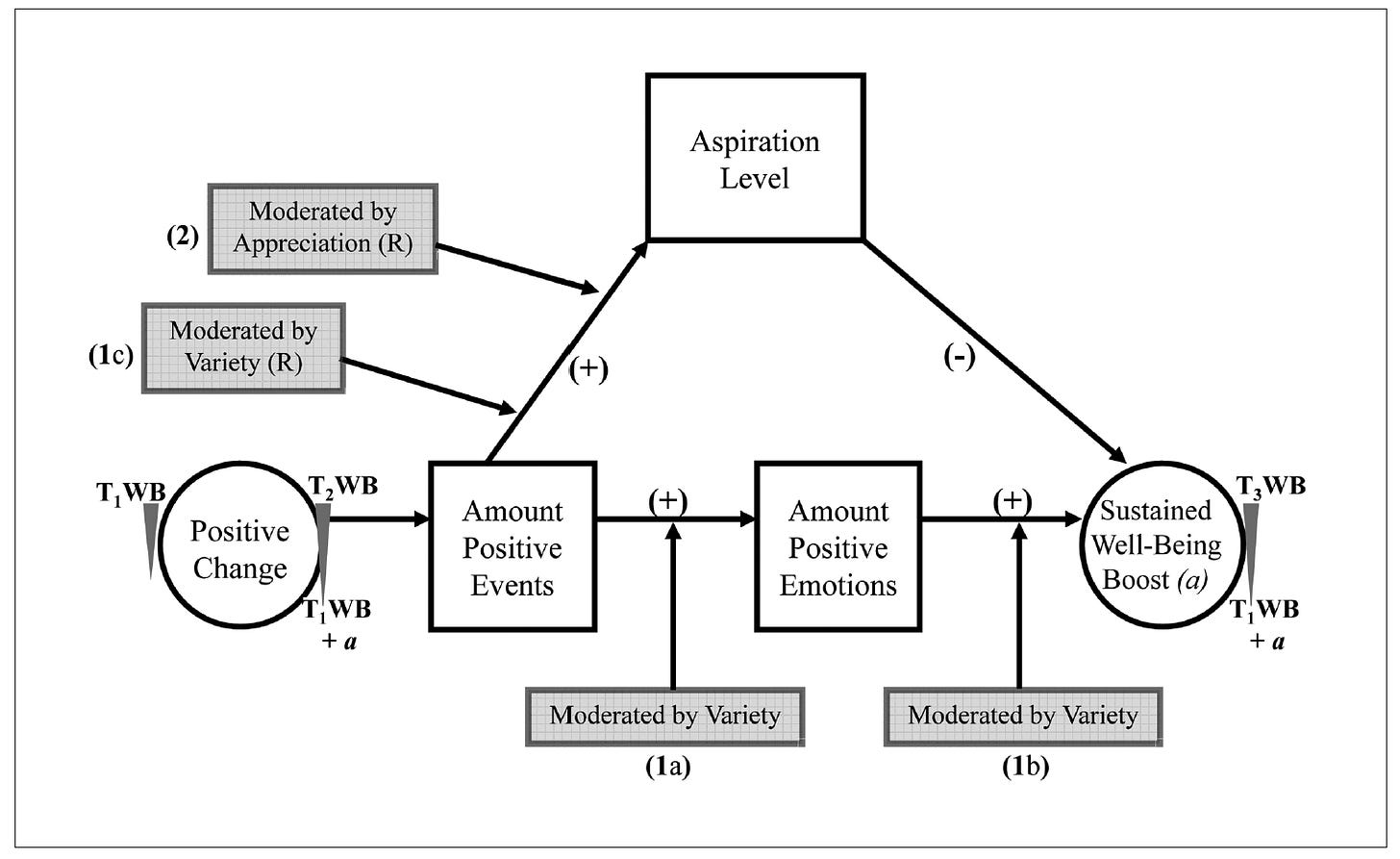

The good news is that we can resist the pull of hedonic adaptation. In true academic psychology fashion, the solution involves a complex theoretical model.

Here’s the basic idea:

Hedonic Adaptation happens for two reasons. In the period of time after a positive life change: 1) we experience fewer positive emotions related to the change (i.e., decreased “warm glow”), and 2) our aspirations increase—we start aspiring to even bigger and better things, taking for granted or even feeling entitled to our new situation.

This same process can happen in all domains of hedonic adaptation, whether that original positive life change is as small as a pair of slippers, or as big as a new house, new job, or new spouse.

So, the key to preventing hedonic adaptation is to try to: (1) keep up the number of positive events and experiences that result from that change, and (2) try to avoid taking the change for granted.

How do we do that?

In a 2012 study that followed 481 college students over 3 months, researchers asked students to report on a positive life change they’d experienced recently. The students’ reported life changes covered the standard college-life fare: new part-time jobs, new relationships, new extracurriculars. As expected, students who reported fewer positive emotions and higher aspirations experienced lower well-being over time. But two key factors made a difference: variety and appreciation.

When students reported that their life changes brought greater variety to their lives, leading to continued surprising or unexpected experiences, they didn’t have that same drop in positive emotions. And when students reported continuing to appreciate the change, even months later, they were less likely to fall victim to rising aspirations.

Follow-up studies suggest that we can all slow the progression of hedonic adaptation in those same ways:

Prioritize Variety. People who are randomly assigned to complete different “random acts of kindness” every week, compared to those who perform the same act every week, are happier. When making changes to our lives—whether it’s a new bike or a new relationship—we should try to maintain novelty, variety, and surprise. We can ride the bike to new locations, or with new people; we can try different activities with the new person in our lives. Even thinking about a life change in new ways can provide the necessary variety to keep it fresh. Take it from the title of this academic paper: “variety is the spice of happiness.”5

Appreciate It. Noticing and appreciating positive experiences is critical to our happiness. The warm glow of those new slippers will last a lot longer if we stop, every so often, to appreciate the joy they’ve brought to our lives, to reflect on how soft they are, to admire how great they look on our feet, to know, even, that they could break and leave us slipper-less at anytime. By appreciating what we have, we slow that steady march toward always wanting more, better, (fluffier).6

Choose the right things. If we want to increase variety and appreciation, it’s easier to do that with certain kinds of things. Experiences (joining a club, learning a skill, doing something we enjoy), rather than material goods, can keep things fresh. Activities that are pro-social (i.e., helping others) and that nurture our relationships can also provide a more lasting boost to happiness. They naturally create more variety, and we’re more likely to appreciate them.

Find your zoo

Maybe this explains why my son seems so happy all the time. Everything is new to him—variety is a given—and he always stops, in his own way, to appreciate things, whether they’re a rare South American bear, or a pool of muddy zoo water.

This holiday season, I’ll continue to find myself on Instagram, scanning gift guides and collecting influencer’s discount codes. I’ll buy those pullovers and chocolate macaroons and slippers, and they’ll make me happy! For a time, that is, until the hedonic treadmill starts pulling me back to baseline.

But I’ll also keep bringing my son to the zoo, and the aquarium, and the library, and the playground, and the grocery store. I’ll keep noticing how his eyes grow wide with wonder. I’ll notice how he points a small, chubby finger at the things that make him happy: the things that were in front of us the whole time. And I’ll try my best to appreciate it.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

It was the San Diego zoo (we were visiting southern California for Thanksgiving), and it was amazing. Highly recommend. Photos, facts, and figures about the Andean Spectacled Bear—I believe his name was Turbo, for those wondering—can be found here.

To be clear: I have nothing against gift guides. I actually kind of love them? Plus, I’m not sure how I would go about buying gifts for my dozens of family members without them.

These ads were literally the first few that popped up as a scrolled through my Instagram. Athleisure pullovers, bespoke macaroons, and then, oddly, an ad for a local orthopedic specialist to treat my “joint pain.” The people in the image were at least 30 years older than me. I just had a birthday, so I was feeling a bit older, but this seems excessive?

Here’s the original 1978 lottery winners study. To clarify: the three groups of participants (lottery winners, accident victims, and controls) were asked to rate both their “general happiness” and “everyday happiness” (i.e., how much pleasure they took in everyday activities like talking with friends or watching TV). In terms of “general happiness” ratings, on a scale of 1-5, lottery winners (average: 4.00) did not differ statistically from controls (3.82). Accident victims were slightly lower than controls (though, at 2.96, still rated themselves above the midpoint of the scale). In terms of “everyday happiness,” lottery winners (3.33) actually rated themselves lower than controls (3.82). There was no difference between accident victims (3.48) and controls. The takeaway: hedonic adaptation is powerful stuff.

Multiple research papers claim that “spicing up your life” is the key to happiness. Unconfirmed hypothesis that the real mechanism behind this happiness is that, when people hear this phrase, they immediately begin silently humming the 1997 Spice Girls hit “Spice Up Your Life.” This was my experience while reading these papers. Also, now I can’t stop. People of the world!…

I do, actually, do this when it comes to slippers. Over a year ago, I got the L.L.Bean Women’s Wicked Good Moccasins, and they changed my life. I wear them at all times while at home, and I often reflect on the fact that I can’t imagine my life before them. I love these slippers as if they were my own child. No hedonic adaptation here, but also, maybe, an indication that I need to get out more.