Hi! I’m Jacqueline Nesi, a clinical psychologist, professor at Brown University, and mom of two young kids. Here at Techno Sapiens, I share the latest research on psychology, technology, and parenting, plus practical tips for living and parenting in the digital age. If you haven’t already, subscribe to join 20,000 readers, and if you like what you’re reading, please consider sharing Techno Sapiens with a friend.

I recently got this question from one of our fellow techno sapiens1 and, after combing through the data, decided it deserved its own post:

I’ve been seeing this chart all over Twitter that shows kids’ test scores declining across the world starting in 2012. So…it’s the phones, right?

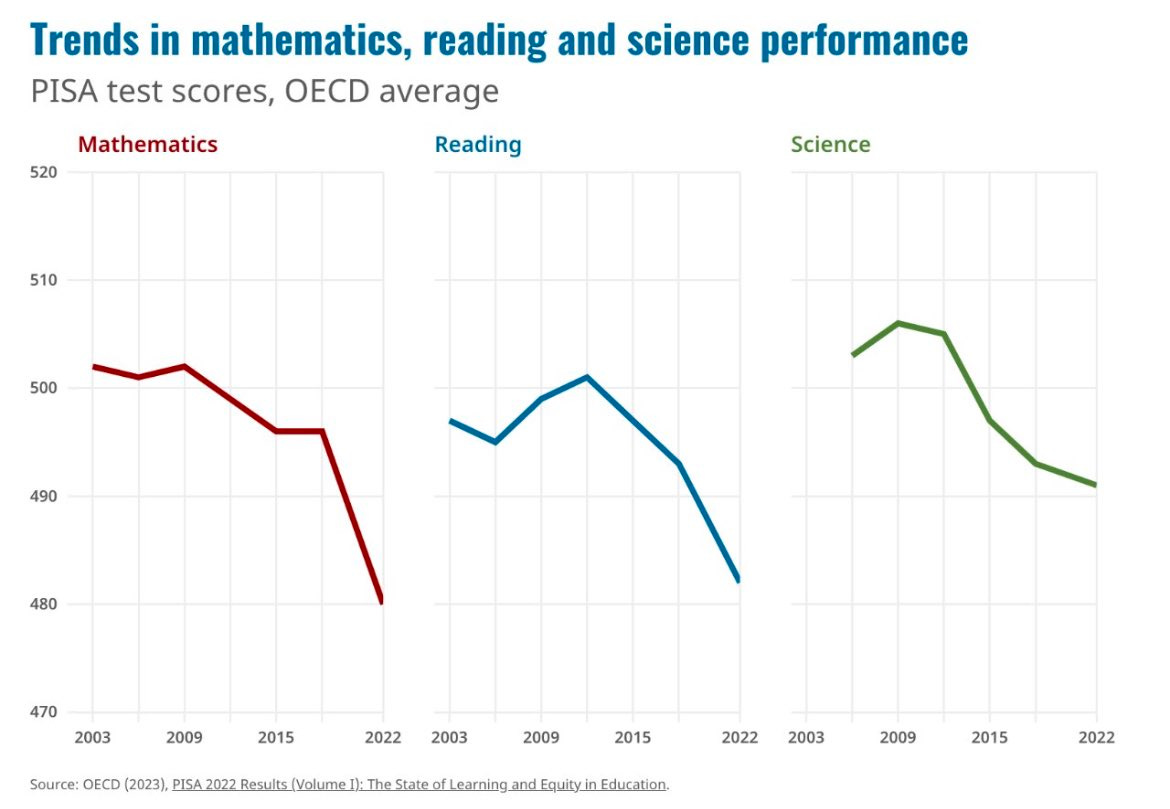

I assume the chart they’re referencing is this one. It is making the rounds on Twitter/X, in various newsletters, and in my husband’s texts to me (you should write about this!)

When I first saw the chart, I had three immediate thoughts: (1) Wow. That seems bad. (2) Let me get a closer look at that Y-axis—wait, what is the range of scores on this test? (3) I’m about to spend way too many hours digging through this data...and I can’t wait.

So first, some background: PISA stands for Programme for International Student Assessment. This is a test given to 15-year-old students every three years, across the world, organized by the Organisation for Economic Co-operations and Development (OECD). It tests three core subjects (Math, Reading, and Science), and takes students about two hours to complete. It has a mean score of 500 points, and a standard deviation of 100 points.

The above chart shows the average PISA scores across countries, from 2003 to 2022. As you can see, they have declined.

Could it be the phones? Absolutely! To be clear: the idea that phones are causing distraction both inside and outside of school hours, and this contributes to declining test scores, seems totally plausible to me—and preliminary cross-sectional data from the PISA report indicates the same. Might it be a good idea to keep phones out of the classroom? Definitely!

But, as often happens when an excerpt of a larger study makes the rounds online, some nuance is missing. Let’s talk about what the data actually show.

U.S. trends in PISA data

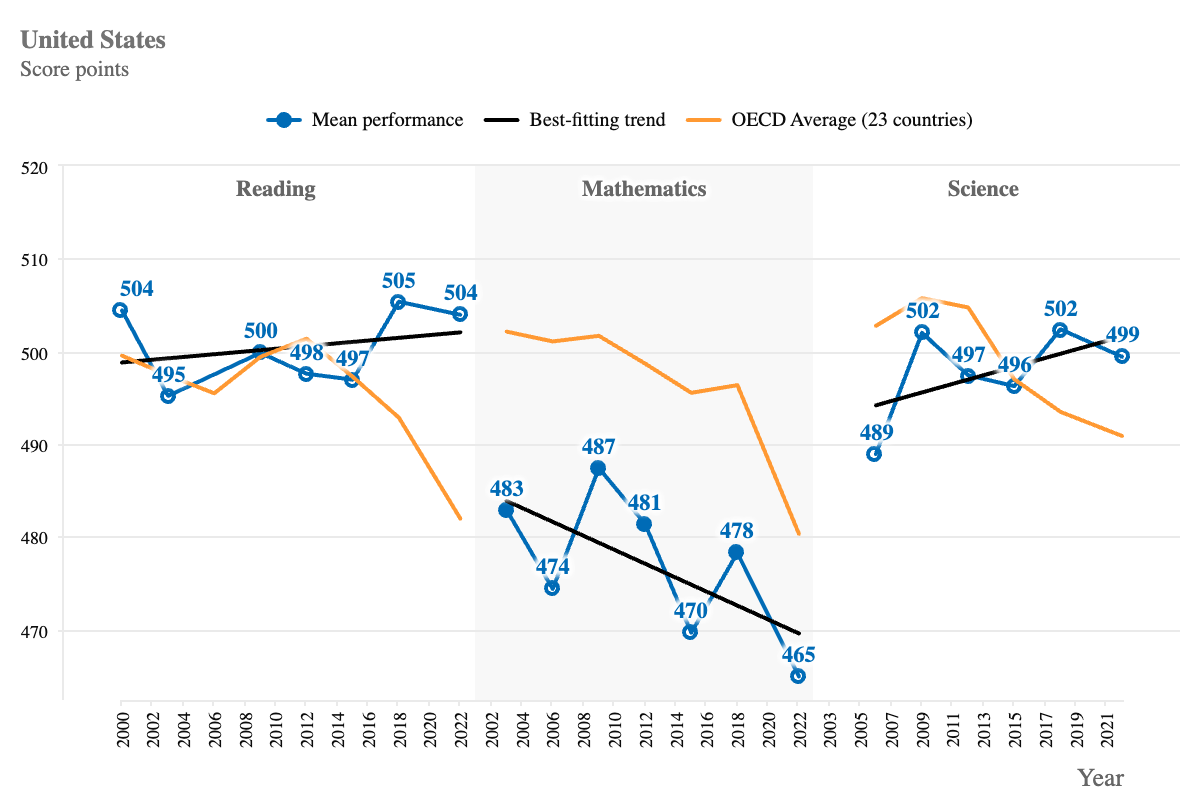

Let’s first take a look at the U.S. data (source). The scary, orange lines here are an average of countries across the globe. The U.S., in blue, shows a different pattern:

In the U.S., scores in reading and science have not changed since 2012. They have declined in math (by 13.1 points). If declining scores are due to phones, why didn’t U.S. students’ scores decrease in reading and science, too?2

In fact, though 29 out of 63 countries showed declining performance in at least two subjects from 2012-2022, that means more than half of countries did not show declines in at least two subjects. If phones are entirely to blame, why wouldn’t nearly all countries—or at least those with widespread smartphone adoption, like the U.S.—show this same declining pattern?

Global trends in PISA data

Now, let’s talk more about that original chart, which also shows average scores across OECD countries globally.

In math, the decline in scores from 2003-2018 is not statistically significant. This means math scores were actually stable from 2012-2018. Remember, we’re talking about a test with a standard deviation of 100 points, so a couple points here and there are just noise (even if a zoomed-in Y axis makes them look larger). There is a significant decline in math from 2018 to 2022, but this could be due to the pandemic.

In reading and science, there is a statistically significant decline starting in 2012. This fits with the introduction-of-phones explanation. But why weren’t math scores declining from 2012 onward, too? Are English and Chemistry teachers more likely to ban phones in the classroom than Math teachers? (Seems unlikely based on my own high school experience).

Summary

In sum: on average, across the world, test scores are down—with unprecedented declines since 2018. This is a problem.

Might it be smartphones? Yes! My hunch is that phones are part of the story, given everything we know from prior research (and common sense). But this data—like most individual studies—isn’t the smoking gun we might want it to be to ban phones from schools. We can reach that conclusion without glossing over the limitations of data like this.

Plus, if there’s one thing we know about phones, it’s that we can’t take everything we see on them (even charts on Twitter/X) at face value. Often, the story is messier than a single chart would make it seem.

Note: if you, too, cannot help yourself from doing a very deep dive on this data, you can find it on the OECD website here. If I missed something, I want to know! Please feel free to leave a comment or respond to this email.

A quick survey

What did you think of today’s Q&A? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

Let this be a cautionary tale to all techno sapiens who’ve considered submitting a question for our monthly Q&A’s…you might just end up with an entire post and multiple graphs in response.

One note on U.S. data: according to the PISA report: In 2022, school participation rates missed the standard by a substantial margin, and participation rates were particularly low among private schools (representing about 7% of the student population)…exclusions from the sample also showed a marked increase, with respect to 2018, and exceeded the acceptable rate by a small margin…Based on the available information, it is not possible to exclude the possibility of bias, nor to determine its most likely direction. In other words, the U.S. is one of 13 countries that did not meet the sampling standards PISA requires. It is possible that this influenced results, but it’s difficult to say whether and in which direction (i.e., higher or lower scores) that might have occurred.

Thanks for providing some much needed context to these charts. While I think it’s clear at this point that there is probably some sort of negative correlation between smart phones and academic performance, it feels like it’s become a popular scapegoat for every issue. When in doubt, blame the phones! Then we don’t have to do any work to see if there might be deeper issues at play. Appreciate you bringing more nuance to the table

Jackie! Thank you for writing about this. We’ve been scratching our heads about these PISA scores since they were released. Spain (and in particular, our state of Catalonia) didn’t do very well. But we went through one of the toughest lockdowns outside of China, and the kids were back in school with both teachers and children wearing masks for well over a year. I can’t imagine a world where this didn’t contribute to the drop in the scores. Did you get any indication as to whether that was factored into to the scoring?

(Also, congrats on the baby! I’ve got our podcast episode almost finished, will be going out in the new year.)