Fixin' My Noggin

Reshaping children's lives, one Instagram photoshoot at a time

Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

A summary for busy sapiens

Today, we’re talking about baby helmets and the online parent communities behind them. Other topics covered:

The strange business of baby helmet clinics

A calendar featuring seasonally-themed photos of babies in helmets

Instagram accounts that double as brand marketing and parent support groups

I’m sitting in the passenger seat of our car, my husband driving, the baby in the back, when I search for the Instagram page.

We’re on our way home from our first appointment at the clinic, which describes itself as the “leading non-surgical treatment provider for plagiocephaly” and the manufacturer of its “FDA-cleared cranial orthotic®.”1 Translation: they make helmets to fix flat spots on babies’ heads.

In recent years, this type of helmet treatment has become a big business. Since the introduction of the “Back to Sleep” campaign, babies are spending a lot more time on their backs. As a result, the number of babies with positional plagiocephaly, i.e., a flattening of the back of the head, usually due to sleeping in a certain position, has skyrocketed2 (as many as 46% of babies are affected, according to some estimates). In the vast majority of cases, the issue is purely cosmetic,3 and not cause for any medical concern. Helmet companies—backed by big-name private equity firms—have jumped in, rolling out clinics across the country and trademarking these “cranial orthotics” at lightning speed.

We’re now leaving one such clinic. The baby, his adorable (slightly flat) head resting in the carseat, is giggling to himself after a quick sneeze.

We, on the other hand, have spent the car ride debating the decision: to get him a helmet, or not? Should we make him wear this thing, 23 hours a day, for anywhere from 4 weeks to 5 months (the estimates weren’t exactly specific), risking heat rashes, discomfort, and—worst of all—disrupted sleep? Will our insurance cover it?

Mostly, we wonder, is it even necessary? It seems like a big undertaking for a problem that’s solely based on appearance. Not to mention, at least one study suggests that in 77% of cases, flat spots resolve on their own (with “repositioning” and/or physical therapy). Of course, we worry that we’ll be in the 23% of cases where it does not, so the data—as is so often the case—only gets us so far. Will we be subjecting him to a lifetime of insecurity over a head that doesn’t look like all the other kids’?

The calendar

On my lap, I’m balancing a stack of papers provided by the office. There’s a report containing side-by-side photos (subtly labeled Normal Head Shape and Your Baby’s Head Shape), an official-looking evaluation report, and a four-step primer on the baby helmet insurance process. There’s also, inexplicably, a calendar.

The calendar features 12 helmet-clad babies dressed in theme. In March, for example, a little cherub wears a ladybug costume, helmet painted red with black spots, and adorned with miniature antennae. A tiny nugget wears a Santa costume, helmet hand-painted with a decorative string of holiday lights, in December.

When I show my mom the calendar later that day, shaking my head in disbelief, she perks up. Those babies are so cute! I look at her incredulously. That’s what they want you to think! Of course, we’re both right.

And then there’s the Instagram account.

At the bottom of each page of the calendar—appearing a total of 15 times—is a call to action to join the company’s Parent Community on Instagram.

So here I am now, on Instagram, getting to know my potential community. The page offers a soothing, blue and green brand palette and friendly aesthetic. The grid is cluttered with bright photos of smiling babies, helmets perched on their heads. It’s also sprinkled with branded graphics labeled things like “Truth or Myth!” “Did you Know?” and “Plagiocephaly Fast Facts.”

It has 17.8k followers.

Online social support, often provided through social media communities, can be incredibly powerful, particularly for parents of children with rare or difficult-to-manage health conditions. A 2016 review, for example, finds that social media groups for parents of children with special health care needs can reduce feelings of isolation, increase coping, and provide needed information and resources.

But this cranial band page feels…different.

Perhaps it’s the knowledge that, in many cases (as in ours), the helmet treatment is purely cosmetic, which makes hashtags like #PlagiocephalyAwareness and reminders that you are not alone feel hollow. Or maybe it’s a certain misplaced search for identity—do I really need to call myself a #HelmetMama?

It could also be the seemingly desperate attempts to integrate this ugly, white plastic baby helmet into existing portraits of perfect family life. We’re normal! The photos scream through filters and smiling faces. Look at our letter boards! “Fixin’ my noggin” or “under construction,” they read. Nothing to see here! Just a picture-perfect family with a cute new accessory.

Or is it just the money-making scheme behind it all? A business page, clearly run by some kind of millennial social media marketing intern, masquerading as a support group? They—we—are a community, after all, of parents and babies and plastic cranial bands, who just happen to be communing amidst the backdrop of a $100M-per-year revenue business that makes your baby’s head rounder.

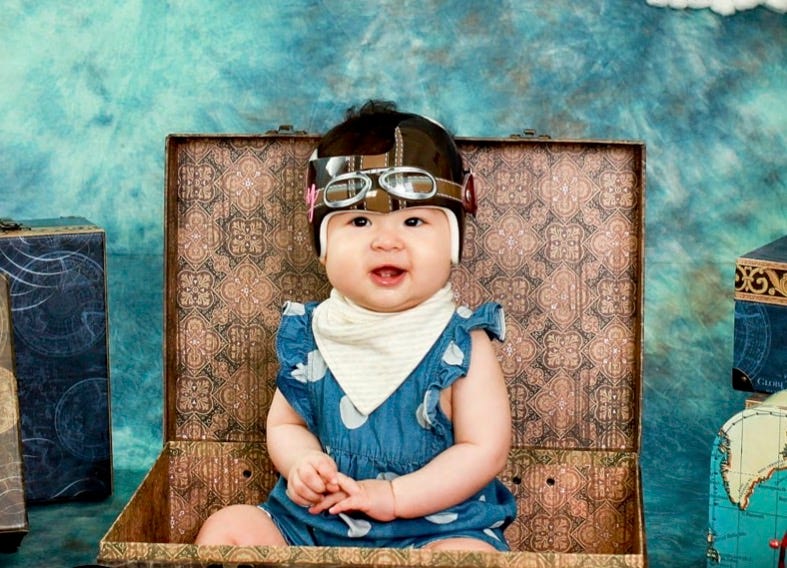

I look closer at the recently posted photos. Are those tiny gold coins artfully scattered in the backdrop of a St. Patrick’s Day-themed helmet baby photo shoot? Is that baby, surrounded by silver-embossed suitcases and an antique globe, wearing a cranial band custom decorated to look like a vintage flight helmet with aviation goggles? Where on earth does one find baby-sized regalia for a helmet graduation photo?4

These babies are so adorable I can hardly stand it. Also, I kind of hate them.5

Reshaping Children’s Lives

As I browse the Instagram page, I can’t shake the feeling I’ve had since we first stepped foot in the office. It’s a feeling similar to the time I went to a kitchen design store, and there was a gleaming, fully-equipped (but non-functional) kitchen on display in the middle of the showroom floor. It looked familiar, nice even, but something was…off. A carefully crafted exterior obscuring something more flawed.

I couldn’t help feeling it was all a ruse—that we were surrounded by play actors wearing scrubs, practicing their parts in a community production of Doctor’s Office. There were all the right props: clean exam tables, posters on the walls with medical-sounded facts, a medical device that took 3D pictures of our baby’s head6. But there was also the trademarked branding on every surface, the slick insurance liaison, the careful dance around the purpose of the helmet (according to our pediatrician, cosmetic; according to the clinic’s informational packet, essential to avoid “important functional implications.”)

Reshaping Children’s Lives, their slogan reads.

I watch an Instagram reel of a couple performing a choreographed dance as they announce their decision to outfit their twin babies with helmets. The feeling I had at the office lingers. That what I’m looking at is a perfectly crafted veneer, masking a much messier reality. That it’s all part of some kind of desperate quest to fit in, to be “normal.”

That we’re all just struggling to figure out what’s real, and what’s just an image, in a world where we’re reshaping our children’s lives—and our own lives—to perfection.

I scroll back up to the top of the page to find a series of highlighted stories. One is labeled “Calendar Tips.” It contains a series of 5 “Top Tips” to “increase your chances of being selected for next year’s calendar.” The requirements include: Original photos only, no filters.

I put down my phone.

Ten Weeks Later

I’m home with the baby after his final appointment at the clinic. He’s done with his helmet treatment.7 I can’t be sure what tipped the scale on our decision to get the helmet. Was it those medical posters on the walls of the clinic? The side-by-side 3D photos? The Instagram letter boards? Or, simply, that universal parental fear—which no amount of data can take away—that your child will be different, that they somehow won’t have a place in this crazy world of vintage flight-themed photo shoots and filtered photos.

I set the baby down on the floor, adorably round face smiling up at me, and give him the helmet graduation certificate. The certificate contains the cranial band trademarked logo, and, for good measure, a few more reminders to join the Instagram parent community.

He grabs the certificate, crumples it beyond recognition, and shoves it into his mouth. I take a photo. I immediately text it to friends and family (he graduated!).

I won’t be submitting it to the calendar.

You may have noticed that I’ve avoided using the actual name of the company and its trademarked cranial band. We don’t do takedowns here at Techno Sapiens, and I wanted to share some thoughts and observations that feel more universal than this particular company. Also, I don’t want to get sued.

For more info, see this not-at-all judgmentally-titled report from the American Academy of Pediatrics: When a Baby’s Head is Misshapen. Did we need to use the word misshapen? Seems a little harsh, particularly when you, like me, are confident your baby’s head is perfect in every way.

There are studies showing associations between plagiocephaly and developmental delays, but it seems highly unlikely that the direction is causal (i.e., that flat heads cause developmental delays). This has not stopped the cranial band manufacturers from touting this research as evidence of the potential for long-term damage due to plagiocephaly.

I later learn of a (presumably) booming custom helmet decorating business, www.blingyourband.com, whose noble mission states: If your son or daughter wears a cranial band, you might feel a little self-conscious about the attention it brings to your infant…Our mission is to take what looks to most folks like a serious medical condition, and make you and your child approachable and fun with a decorated band. They offer hundreds of themed decals (e.g., “boho rainbows,” “Top Gun”), specially-designed helmet paint, and a custom decoration service.

It goes without saying that this is a joke. I obviously do not hate any babies. Except the one who growled in my baby’s face at library class this week and made him cry. I’m watching you, Liam.

At the office, our assigned clinician made no effort to hide her displeasure at our skepticism of the whole enterprise. Let’s call her Susan. Would we be able use the measurements provided by their proprietary 3D imaging system to track our babies’ progress? We wondered. This was the most idiotic question Susan had ever heard. You’re using straight-line measurements to describe a round object. They’re obviously just estimates. [Not perfectly round! I felt like saying]. Is there a chance that it will resolve on its own? I asked, armed with the 77% statistic I’d read previously. Susan did not hesitate. No. This is the most confident answer I think I’ve ever gotten from a medical professional. This lady was not messing around.

For those who are curious, the helmet treatment seems to have worked. Our baby’s head shape has noticeably improved. What has not improved is our ability to stop ourselves from rubbing his precious, newly helmet-free head

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst