Is this app the next Instagram?

Also, who am I?

Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

Summary for Busy Sapiens

BeReal is now one of the most downloaded social media apps in the App Store.

From January 2021 to April 2022, its daily active users grew from 10,000 to 2.93 million.

BeReal prompts users to post a photo (with front and back camera) once per day during a two-minute window

But what does it mean to be authentic when the features of our environments, both online and off, shape our behavior?

During the pandemic, my husband and I left the city, moved to the suburbs, got married, began working remotely, and had a baby1. Many of our friends did the same.

As the haze of new parenthood settled, and the world started opening up again, we began to take stock of our surroundings. Where were we?

It was as if we were actors in a play, suddenly finding ourselves in a new scene. The old props had been whisked away—cardboard renderings of tall buildings, streetlights, yellow cabs—and the longtime friends who once served as scene partners had exited stage left. And now here we were, looking bewildered at the new scene around us, a house and baby dropped in, ready to start Act Two.

Who were we supposed to be in this new place? Before, we were people who tried new restaurants, and met up with friends for drinks, and traveled on the weekends, and went to fitness classes, and commuted to work. Now, in a new house, in a new town, working remotely with a new tiny human and a nagging fear of public, indoor spaces, who were we? Were we still ourselves when we strapped the baby into the stroller and wandered around the new neighborhood, stopping to chat with friends we’d just met?

When our identities are so tied to our surroundings, what happens when our surroundings change?

Let’s talk about BeReal

I first heard about BeReal in April, during a virtual visit to the high school classroom of one of my favorite former teachers (thanks, Ms. Stewart!). After learning about it from the students, I began seeing it everywhere. And for good reason. Between January 2021 and April 2022, BeReal’s daily active users went from 10,000 to 2.93 million. It’s currently one of the most downloaded apps in the App Store. Last month, it reportedly closed its Series B at over a $600M valuation, prompting many headlines calling it “buzzy” and lots of rocket emojis 🚀 on Twitter.

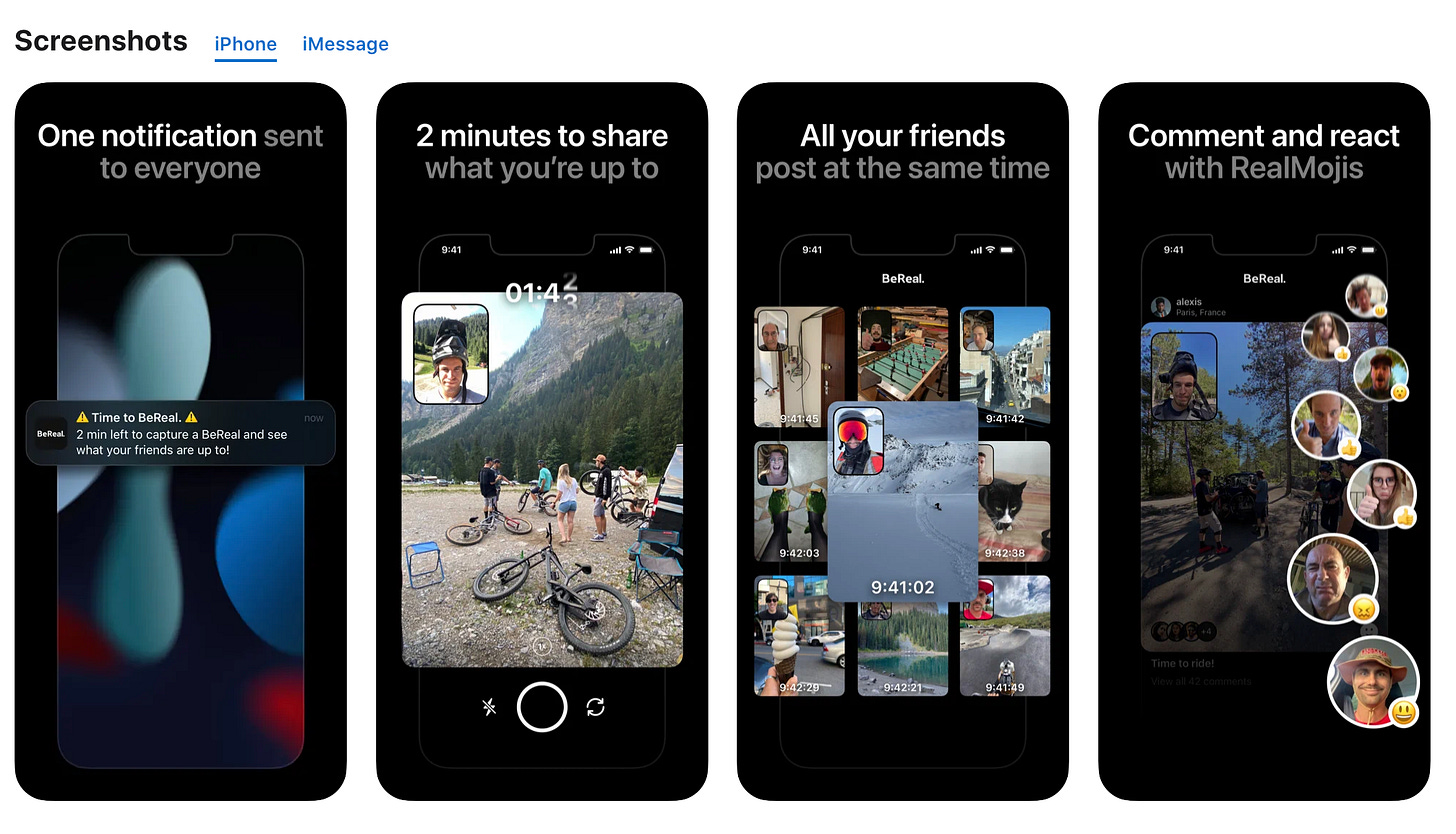

The premise is simple. Once per day, you get a notification informing you that you have two minutes to take a photo. You take the photo, which captures images simultaneously with your phone’s front and back camera. Then you post it. If you’re late, the app notifies your friends. If you retake the photo, your friends can see that too. Your friends comment on it and leave “RealMojis,” or small selfies of their faces reacting to your post. You do the same for them. 24 hours later, it’s all gone, and you start over again.

I downloaded the app in May and texted some friends, asking (begging) them to join me on BeReal for “research purposes.” It’s the first time I can remember doing this since the early days of Instagram, over a decade ago. During that time, our Instagram posts have evolved—from quirky scenes of the day-to-day (in my case, a wild turkey crossing the road and a pair of rollerblades I found at Target) to carefully curated images of our children. Our feeds have evolved too, from delightful glimpses of each other’s lives to a series of influencers, brands, and an occasional portrait mode vision of “parents night out.”

While I wait for my fellow millennial neoliths to join BeReal, fielding protests like “I don’t need anymore new apps on my phone!” and “What is this?!”, I ask two students from Ms. Stewart’s class, Cait and Skylar, to fill me in over Zoom. They’ve been on the app since March.

Why do you think BeReal is taking off so much? I ask.

Cait weighs in. I think it’s because it's different than other social medias. The fact that it captures both your front and back camera, and that it gives everybody simultaneously a time to post, are very unique. And I think that's very different than Instagram, where you can post and edit whatever you want. You can't edit your BeReals. You have to post it how it is. You can retake it, but then other people will see you retake it. You can't change anything about yourself. It's completely real.

Skylar adds: I think the best part about it is that it normalizes imperfection–compared to Instagram, which really strives to show off the perfections of life and create this stereotypical body image.

The promise of BeReal is that we can be exactly who we are: imperfect, unedited, in-the-moment. But can we ever truly be ourselves online?

The medium is the message

One of the first people you learn about in any communications class—or, when banging your head against a keyboard trying to write a dissertation about social media—is someone named Marshall McLuhan. A Canadian communications theorist, in 1964 he coined the phrase The medium is the message. The concept is simple: the medium we use to communicate affects what gets communicated—so much so, in McLuhan’s mind, that the medium may become even more important than the actual content of the message.

You’re likely aware that social media did not exist in 1964. Despite this, McLuhan’s thinking has been highly influential in our understanding of modern media effects. Any given social media platform has features that shape the way we interact. Instagram, for example, involves high levels of permanency (our posts stick around for awhile), publicness (we have a big audience), and asynchronicity (we can take our time posting). We act differently on social media than we do in person because of these features. When we have more time to think about what we say and do, we engage in selective self-presentation, choosing certain details, photos, and text to present ourselves in a positive light2. The medium itself shapes the messages we convey.

Here’s an analogy that, for inexplicable reasons, does not appear in McLuhan’s book. Let’s imagine I’d like to drink some wine. It is impossible to do this without putting it into something—I can’t just grab at it, the sauvignon blanc dripping through my fingers as I try to bring it to my mouth. I need a vessel. And that vessel is going to affect, ever so slightly, how I perceive it. If I drink it out of a wine glass, it’ll taste great. If I drink it out of my child’s overpriced minimalist sippy cup, it will taste a little weird.

We like to think of our online presence as wine that’s just, somehow, there. No vessel, just us, exactly as we are: a simple, accurate reflection of our true selves. But it isn’t. It’s always mediated—by the presence of a camera, the knowledge of an audience, the time to pause and click out a caption. The vessel will always shape how we’re perceived (and how we perceive ourselves).

And yet, is there ever a time in our lives when we’re truly ourselves? When we’re entirely, indisputably authentic? Just as the features of the online world shape our behavior, so too do the features of other contexts. We’ll present slightly different versions of ourselves at work versus at home, at a party versus our children’s school, and at a gathering with friends we’ve known since childhood, versus one with friends we just met.

We are always making choices about which aspects of ourselves to share—what details to divulge, what stories to tell, what questions to ask. There’s always a vessel in real life, too.

A quest for authenticity online (and off)

There’s a growing movement lauding “authenticity” on social media. And for teens, who’ve grown up watching the adults in their lives curate flawless visions of family life on Facebook, the drive to appear authentic is everything. Listen to the lyrics of any popular song and it’s clear that to be “fake,” the opposite of authenticity, is a fate to be avoided at all costs.

Late last year, we saw TikTok influencers encouraging users to forgo Instagram’s filtered photo shoots and simply be themselves on Instagram.3 Suddenly “casual Instagram” (versus “performative Instagram”) became the ruling aesthetic among teens, complete with “photo dumps” (a group of seemingly random photos posted all at once) and blurry photos that convey I don’t even care enough about this to take a clear photo.

Then came the backlash. Not only do we need to look good in our Instagram photos, users lamented, but now we need to pretend that we didn’t know (or care) the photo was being taken?!

And then, rising up from the ashes, there was BeReal, to pick up the broken pieces and make us real again.

On the app store, BeReal proclaims: “BeReal is your chance to show your friends who you really are, for once…BeReal won't make you famous. If you want to become an influencer you can stay on TikTok and Instagram.”

I ask Cait and Skylar about what it means to be authentic on social media.

I don't think Instagram is authentic in the same way as BeReal, Cait notes, Because now, on Instagram, we see people forcing themselves to pose a certain way and it's like, oh look, this is authentic. But you're posing that way on purpose. No matter what you do [on Instagram], you're still not authentic. BeReal just kind of captures the moment… It's kind of just how you are in that moment is what is presented to others.

Cait and Skylar describe the features of BeReal, a series of checks and balances the app implements to enforce its vision of authenticity: Simultaneous front and back camera (you can pose for a selfie, but you’re not gonna pose for that back camera), 2-minute timer (you don’t have time to figure out a pose…you’re not going to fix your hair, fix your makeup, or whatever), no importing photos (you’re taking it in that moment), and a view into how many times the user retook their photo (so it tells you, is this authentic or not?)

The medium—even one that’s been carefully positioned in opposition to Instagram—shapes the message. But on BeReal, the pressure to appear a certain way, to capture a certain version of oneself, seems (for now) to be a more distant concern.

As we wrap up our conversation, the students mention that they’ve been asked to take a screenshot of our Zoom meeting. I assume it’s for the school’s website. I want to give you a heads up, Cait says before she takes it, because I know we’re not being real.

We all laugh.

Where we are is who we are

Slowly, small red notifications appeared on my BeReal Requests page as friends set aside their social media cynicism and joined.

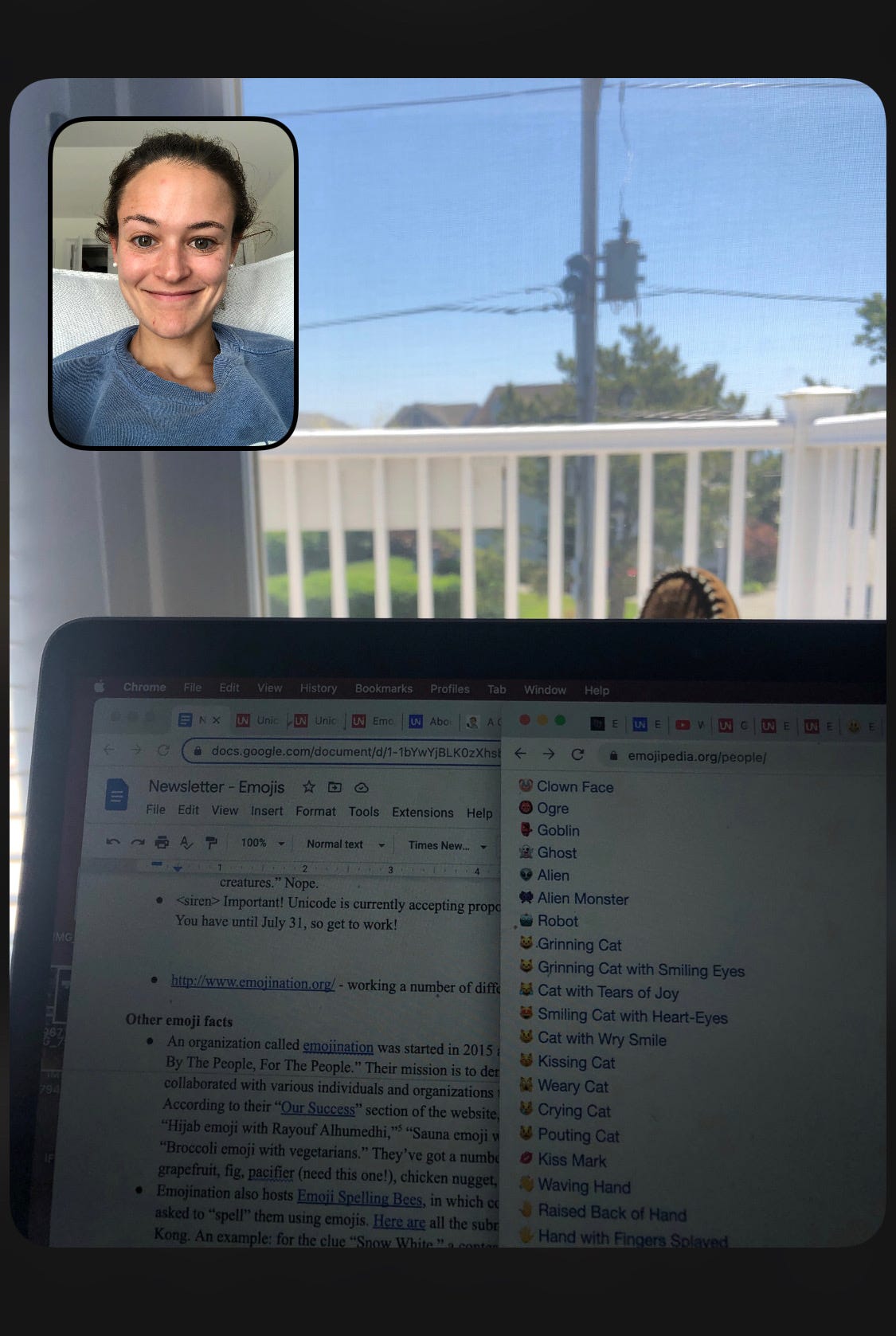

I delighted at a snap of a friend and her baby in the midst of a bedtime routine. I laughed out loud at a collection of VHS tapes in my friend’s parent’s basement, where she was (unfortunately) quarantining after a COVID exposure (her posts were very consistent for five straight days). I was thrilled to see a friend at a candy convention—exactly what I’d imagined her job entailed when she began working for a candy company. And I loved catching glimpses of friends’ laptops, giving quick windows into the numbers and words and syntax that fills the minutiae of their workdays.

As adults, it’s rare to see these moments—not the Instagram moments, the weddings and the babies and the professional family photos—but the everyday ones. The beautifully boring ones. And it’s especially rare in these post-pandemic days, as we’ve all plopped down in our own, scattered theater sets, filled with new features and new people, where we’re all learning who we are again.

I get a notification that it’s time to BeReal. I turn the camera on myself and the baby. He’s crying—mom’s already too fake for him—so I wait a few seconds. I make some noises, he starts to smile, and I smile too, quickly snapping the selfie, a view out the window of our new house, into our new town, captured in the back camera. I smile as I chat with friends in the comments.

I like this version of myself.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

This quick description of our moving, getting married, and having a baby leaves out a few important steps. See: Un-inviting family and friends to a COVID-cancelled wedding. Moving from one apartment to another. Soon realizing the pandemic was not, in fact, ending. Moving again and putting everything in storage. Living out of a giant suitcase. Maniacally laugh-crying when said suitcase exploded on our way to catch a flight, scattering possessions all over my parents’ lawn. The unexpected joy of living with siblings and parents, including nightly family meals reminiscent of our childhood. And after frantically scanning Zillow for eight months, a wave of sheer relief at 39 weeks pregnant, when we moved into our house.

Here’s a study that illustrates how one feature of social media, asynchronicity, impacts our self-presentation behavior. In 2013, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania recruited 218 students and asked them to have a short conversation with a partner about any product or brand that they wanted to discuss. Before entering the conversation, some students were told that they were being evaluated—that their partner would rate how cool they were at the end of the conversation. In addition, some students were assigned to have the conversation orally (face-to-face), and some written (using instant messenger). Later, a separate group of students coded how “interesting” the products or brands were that the subjects chose to discuss. Products like the iPhone and augmented reality glasses were rated more interesting, and those like nail polish and toothpaste were rated less interesting.

What did they find? When students had the conversation via instant messenger (versus verbally), they chose more interesting topics to discuss. This effect was even stronger when they were told they’d be evaluated. In other words, when we have time to think through how we present ourselves—and especially when we’re aware that others are evaluating how “cool” we appear—we try to optimize the version of ourselves that is expressed.

I do find it odd that the “casual Instagram” trend was born of TikTok. Because nothing says “be yourself” like an influencer telling you to do so.