Welcome to Techno Sapiens! I’m Jacqueline Nesi, a psychologist and professor at Brown University, co-founder of Tech Without Stress, and mom of two young kids. If you like Techno Sapiens, please consider sharing it with a friend today. Thanks for your support!

9 min read

And we’re back!

Last week, we talked about the research behind school cell phone bans. To summarize: we have evidence that smartphones can be distracting and interfere with in-person socialization. We also have evidence (though imperfect) that limiting phone use during the school day can have positive academic outcomes. Exactly what school policies should look like, though, is less clear.

So, this week, we’re getting into the nitty-gritty: how are schools actually doing this? What are the options when it comes to school cell phone policies? What do teachers and parents think?

Let’s get to it.

What are the options?

The idea of a “cell phone ban” would seem like a straightforward concept (i.e., no phones!). In actuality, the range of policies, many of which are classified as “bans,” is sizable.

There are three basic categories of school phone policies: (1) Banning phone use entirely during the school day, (2) banning phone use during certain parts of the school day, or (3) having no policy at all, which generally means leaving it up to individual teachers.

Here are the options:

Policy 1: Phones are entirely banned

How it works: Phones are not allowed at any time during school (unless students have a medical condition, disability, or other extenuating circumstance for which they need one). There are a few different ways that schools implement this. Options include:

Phones stay at home.

Phones are “turned in” at the beginning of the day, and stored there for the entirety of the day. Schools use various vessels for this: safes, baskets, hanging pocket holders, phone lockers, etc.

Phones go in special pouches, like the Yondr, which can only be opened by swiping the pouch on a special magnet (which might be at the entrance to the school).

Phones stay in students’ lockers.

Phones stay in students’ backpacks.

Note: some phone “bans” apply only to smartphones, and others to all mobile devices

Here are some examples of phone ban policies from real elementary, middle, and high schools, courtesy of Away for the Day.

Policy 2: Phones are banned during certain parts of the school day

How it works: Schools designate times of the school day where phones are or are not allowed. Options include:

Phones banned during class time altogether

Phones allowed during class time, but only for teacher-approved educational purposes (e.g., calculators, educational apps)

Phones banned during lunch

Phones banned during passing periods between class

Phones banned in bathrooms

Phones banned during after school activities or extracurriculars

Policy 3: No policy

How it works: Schools do not have any rules around phone use. In many cases, teachers make rules for their own classrooms. Teachers may have a range of classroom policies, which might include:

Hanging a pocket holder on the door in which students deposit their phones at the beginning of class

Asking students to keep their phones out of sight (in a backpack or pocket)

Integrating phone use into classroom activities (e.g., with educational apps, or to look up information)

Allowing students to use phones after completing in-class assignments

What are schools currently doing?

According to nationally representative data,1 a total of 82% of U.S. public K-12 teachers say their school or district has some kind of cell phone policy. That number is higher among middle and high schools, with 97% of middle schools and 91% of high schools saying they have a policy.

Determining what, exactly, those policies entail is a bit more complicated.

The National Center for Education Statistics reports that, as of 2022, 77% of U.S. public schools “prohibit non-academic use of cell phones or smartphones during school hours.”

But what does that look like in practice?

According to a 2019 nationally-representative survey of 210 U.S. public middle and high school principals:

84% of middle schools and 75% of high schools prohibit phones during class time.

67% of middle schools and 31% of high schools prohibit phones during lunch or recess

73% of middle schools and 41% of high schools prohibit phones during transitions between classes

A more recent 2024 survey of school administrators (not nationally-representative) finds that just over half (54.6%) of schools require students to keep phones in lockers or pouches throughout the school day (except for emergencies).

And are these policies effective?

It varies.

About 30% of teachers, including 60% of high school teachers, say that enforcing school cell phone policies is very or somewhat difficult.

Despite the majority of schools prohibiting phone use, many high school (59%) and middle school (42%) principals say that students are using their phones during class.

In fact, a 2023 survey of 11- to 17-year-olds by Common Sense Media (not nationally-representative) found that 97% of adolescents were using their phones during the school day, for a median of 43 minutes. A telling quote from a tenth grade student in this survey:

For my school, we do have a phone policy and we're not technically allowed to have it out during class, but a lot of people do in spite of that. And definitely, I think if you track kids at my school, their phone usage, you would definitely see them checking their phones, and then checking Snapchat during class.

What do teachers and parents think of phone bans?

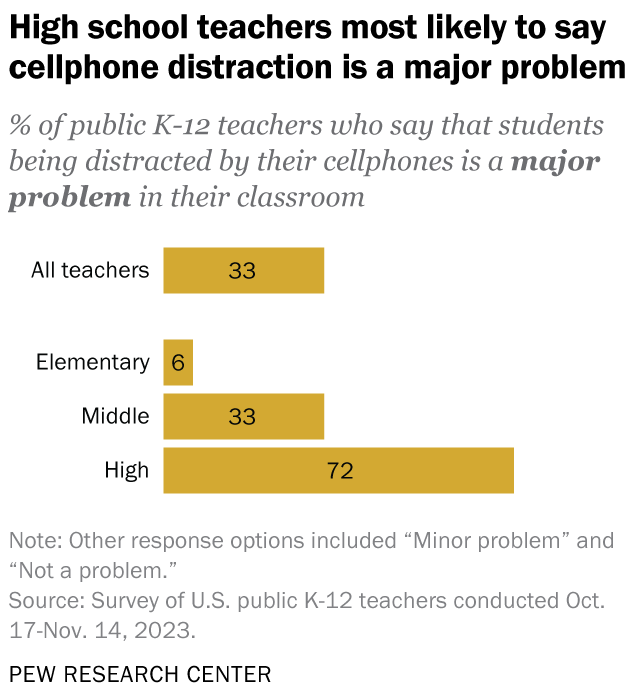

Let’s start with teachers. Among public K-12 teachers, 33% (including 72% of high school teachers) say students being distracted by their phones is a “major problem” in their classroom.

The vast majority of school principals (between 90 and 97%) believe that schools should have a phone policy, but we have less information on what they think those policies should be.

According to one recent survey of public school K-12 educators (members of the National Education Association), 83% support policies that prohibit phone use during the entire school day, 90% support policies that prohibit use during instructional time, and only 31% support policies that would leave student phone usage up to individual teachers.

In other words: teachers are finding students’ phone use to be a problem, and many seem to support policies that would place stronger limits on it.

Now, what about parents?

In a 2023 National Parents Union survey of 1500 parents of K-12 public school students:

79% of parents said students should be allowed to use phones “sometimes” (e.g., banned during class but allowed at certain times outside of class)

Only 10% said phones should be banned at all times

Among parents in this sample whose children take their phones to school with them, they cited the following reasons:

So that their child can get in touch if there is an emergency at school (79%)

So that they can get in touch with their child to find out where they are when needed (71%)

To coordinate transportation to and from school (54%)

To communicate about appointments (e.g., doctors) that they need to leave school for (48%)

To communicate with them about their mental health or other needs during the day (40%)

Worth noting: these results come from parents who “opted-in” to take this survey, so they may not be representative of all parents. That said, it seems clear that many parents favor policies that would allow them to contact their child during the school day as needed.2

Final considerations

As I shared last week, I believe that schools should aim to limit phone use during the school day as much as possible. That said, there are a range of policies that can support this goal. Schools differ considerably, as do the students, teachers, administrators, and parents who make them up. What works at one school will not work for all schools.

What may matter more than any specific policy is the implementation. How are policies communicated and enforced? Are parents and students on board? Do teachers have the support and resources to make them work?

Here are some final considerations for various phone policies:

Logistics

Collecting students’ phone at the beginning of the school day may sound simple, but for a large student body, this can turn surprisingly complex. Where to store them? How to keep them secure? What if a phone breaks or goes missing? How to collect (and return) them one-by-one without using up precious hours of the school day? Some schools have this all figured out. For others, it may be more feasible to have students turn off phones and store them in lockers or backpacks.

Cost

Options range from high-cost (e.g., Yondr pouches can be $15-30 per student) to totally free (e.g., students storing in backpacks).

Student learning

Some schools find it to be highly beneficial to allow students to use phones for academic purposes in the classroom, and with the proper parameters around this, they may find that student distraction is not much of an issue. If it’s not broken, there may be no need to fix it. In other schools, this is clearly broken, and there is a need to fix it to limit distractions for students and teachers.

Note: one argument for less stringent phone policies is that students need to learn to manage their use of technology as a general life skill. While this is important, I would argue that part of learning to manage phone use is having institutions (like schools) set norms where phone use is prohibited or highly limited, and learning to stick to those limits. Not to mention: phones are designed to keep our attention. Even adults have difficulty regulating their use. Expecting students to do this on their own is not reasonable.

Parent concerns

Schools often cite parents’ resistance to phone bans as the primary reason to avoid them. In some cases, parents want to be able to contact children to coordinate transportation, appointments, etc. In others, parents are concerned about contacting their children in an emergency (e.g., school lockdown). Any phone policy should take these concerns into account, creating realistic and clearly-communicated options for parents to get in touch when needed.3 It is also important for parents to know that phones can actually make students less safe during an emergency.

Enforcement

Policies should aim to ease the burden of enforcement on teachers as much as possible. Any phone policy will require resources to enforce, and support from administrators is essential. A statewide mandate, for example, will do little if the burden rests entirely on teachers to implement it. At the same time, a clear school policy with support from the entire community (administrators, parents) may actually alleviate some of the burden on teachers.

That’s all, folks

And so concludes our two-part series on phones in schools. Now, I want to hear from you! What did I miss? If you’re a teacher or school administrator, what do you think? As a parent, what school policies would you support? Let us know in the comments!

Resources

Should schools ban phones? (Part 1 of this Techno Sapiens series)

Away for the Day and Phone-free Schools Movement offer ideas for specific school policies and resources for parents and educators

A database of “phone-free” schools

Collaborative review document collecting research on school phone bans curated by Jonathan Haidt and Zach Rausch

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

Quick reminder: a “nationally-representative sample” is a group of people that are randomly selected and intended to reflect the demographic makeup of the country (e.g., by age, gender, income, race, ethnicity, etc.). These types of samples are hard (and expensive) to get, but they generally result in more accurate data than others.

For example, other sampling options might include “opt-in” (e.g., you advertise something like “take our survey about phones in schools!” and people click the ad) or “convenience” (e.g., you send a survey out to people who have signed up for the mailing list of your nonprofit, whose mission is to remove phones from schools). You can see why the latter two options might result in a more biased sample.

You’ll notice that we’re missing the opinions of one key group here: students themselves. I have not been able to find representative data here (please send it my way if you have it!) The little data we do have suggests—unsurprisingly—that students have mixed opinions.

Some students like having their phones for academic reasons, to plan meetups with friends (e.g., during lunch), or to coordinate with parents. Others find that the climate of the school improves when phones are away, including less distraction and online bullying. Still others finds that offline bullying increases without phones, or that they find themselves using their phones more after school to compensate for lost time. [Many thanks to my colleague in the Netherlands for sharing this research report on the issue, and very kindly translating the key points from Dutch to English]. Here’s also an interesting New York Times piece with quotes from students on this issue.

I teach high school at a well resourced public school with 2,000 students. Last year, after a thoughtful planning and roll out, our administration came out with an "off your body/out of sight" policy for all classrooms. We spent time during our opening days learning the policy and coming up with strategies to implement it school wide. The impact was immediate and game changing. Until it wasn't - maybe around December? I'm positive that there are a few Super Teachers out there who have the skill and fortitude to keep up their vigilance and maintain the policy, but for the merely very good teachers of the world, it's just impossible. At a faculty meeting in the spring, at a small table that included the usual range of teacher personalities ('it's all about relationships", "we need to empower students to make the right choices", "they need clear, consistent, real consequences", "let's ask students what they think") the feeling on phones was unanimous: Ban them. Now. I think any money we are spending on ANY initiative to impact student learning and mental health would be better spent on Yondr pouches. Good, smart, effective teachers and administrators and parents are all trying to address this problem - it's incredibly hard when we are dealing with such an omnipresent, highly engaging, distracting device that has become integral to how students navigate their lives. I just don't see how half measures can make an impact.

Great summary! And hit upon a key point: “A statewide mandate, for example, will do little if the burden rests entirely on teachers to implement it.”

To me, it seems like there needs to be district and school-level conversations with the entire community on how to approach cell phones. My kids are only in elementary, but I grew up without cell phones, and I think there can be a way forward but need to some collaborative, community-level problem solving.