Should you monitor your kid's phone?

Tech Parenting Part 2: Using Ask, Look, and Listen for more effective parental monitoring

This is the second in a series of posts on parenting around technology and social media. You can find the first post here. Most of this will be focused on teens, but some may also apply to younger or older kids (or really, any human in your life). Have a specific tech parenting question? Send it my way!

11 min read

Parents: sharpen your pencils and take your seats. It’s time for a quiz.

Want to see how you did?

This quiz—like most of parenting—has no right answers. Instead, all we have is some data. These questions come from surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2016 and 2018, with thousands of parents of 13- to 17-year-olds across the country.

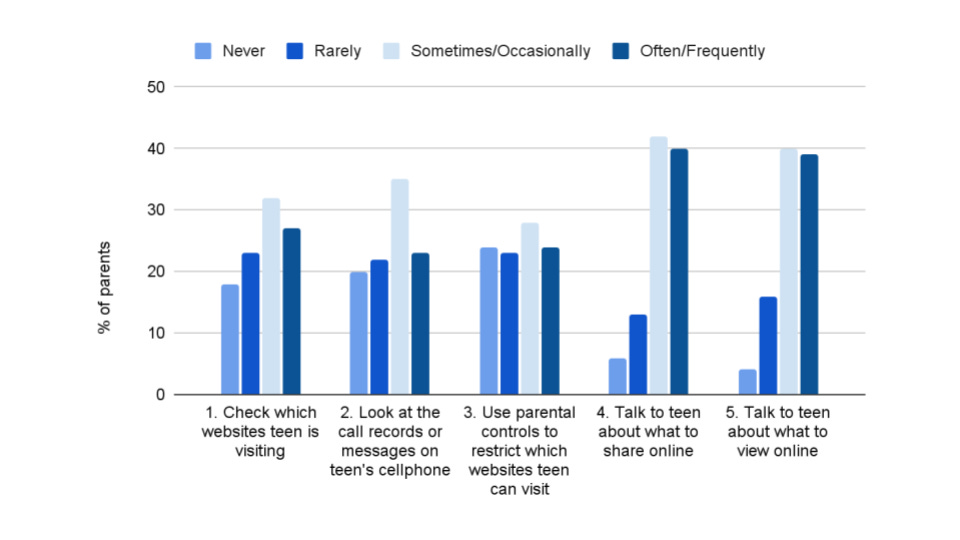

Want to see how your answers compare to other parents? Here’s how things shook out:

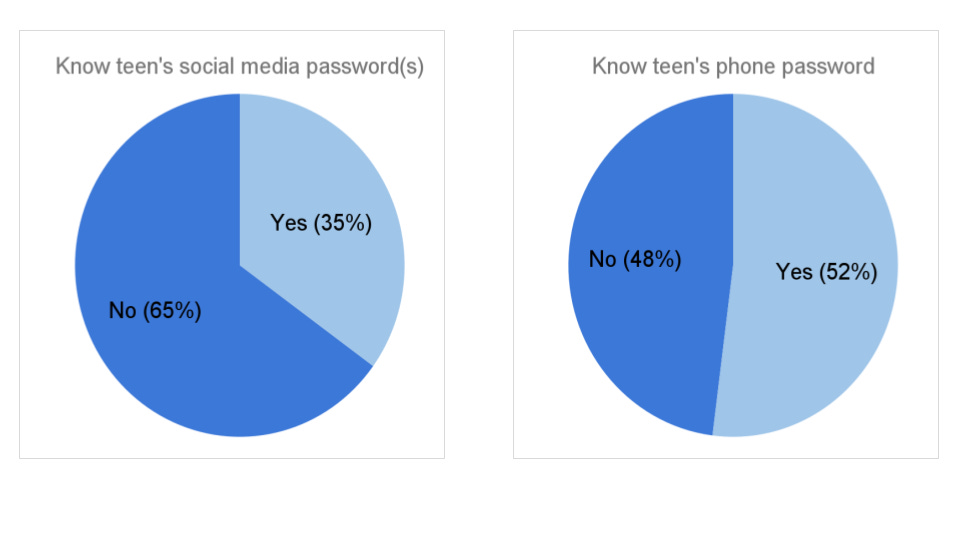

When it comes to supervising their teen’s online activities, a total of 59% of parents say they at least sometimes check the websites their teen visited, 58% at least sometimes look at their teen’s call records or text messages, and 52% at least sometimes use parental controls. How about password sharing? A little more than half of parents know their teen’s phone password. A little more than one-third know their teen’s social media password(s). And what about good, old-fashioned talking? The majority of parents—82%—at least occasionally talk to their teen about what to share online, and 79% about what to view online.

What to make of these numbers? With the exception of talking to their teens about their online behavior—which most parents seem to do—there is actually very little consistency in the choices parents make about supervising their teens’ phone use. Parents are somewhat evenly split on various monitoring behaviors. This means that whatever you’re doing, whether you choose to share passwords or not, or whether you choose to check your teen’s browsing history or not, you’re not alone.

Of course, these numbers can only tell us so much. They do not speak to how parents can make these decisions, or how they can balance teens’ need for privacy with the need to keep them safe. They do not address the spectrum of possible monitoring strategies, or when parents should think about using them.

Welcome to Tech Parenting, Round 2. Let’s dive in.

First, some background. What is parental monitoring?

As with most simple concepts, academics have taken “parental monitoring” and imbued it with a complexity that is equal parts annoying and, in the end, kind of useful. There has also been the standard 30 years of passionate debate1 about how to define and conceptualize it.

During the 80s and 90s, perhaps inspired by decades of Public Service Announcements asking, at 10pm, do you know where your children are?, parental monitoring was defined exactly how you’d expect: “a set of parenting behaviors aimed at paying attention to and tracking the child’s whereabouts [and] activities”. Studies found that teens whose parents monitored them were less likely to do problematic things like break the law, smoke, drink, and skip homework. This is obviously a good thing. We want our kids to be safe, to stay out of trouble, to do well in school.

However—and this is key—the way researchers would measure “parental monitoring” in these studies was often by asking parents something like “how much do you know about what your teen does in their free time?” So, in the midst of Y2K panic and partying like it was 1999, researchers then had a seemingly obvious revelation. What if it wasn’t “parental monitoring” they’d been measuring, but actually parental knowledge? And what if parental knowledge happened in ways beyond just “parenting behaviors aimed at paying attention to and tracking the child”? Maybe monitoring wasn’t all about parents tracking their kids’ whereabouts. Maybe the parents who knew more about what their kids are up to did so simply because their kids were more likely to tell them. Or because they were just most likely to ask.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that parental monitoring is associated with a range of positive teen outcomes, including lower depressive symptoms and fewer risky or dangerous behaviors. But what constitutes effective parental monitoring seems to be inextricably tied to practices that increase parental knowledge. As such, current conceptualizations of parental monitoring now encompass a broad collection of both parent and child behaviors, all of which are geared toward, simply, knowing what your child is up to day-to-day.

There are at least three critical pieces2 of parental monitoring:

Teen disclosure, or teens telling their parents stuff

Parental solicitation, or parents asking their teen stuff

Parental supervision, or parents keeping an eye on where teens are and what they’re doing.

Now, how do we apply these practices to teens’ social media and phone use? In many ways, monitoring online behavior is harder than its offline counterpart.

You can’t, as my parents used to do, casually plop down on the living room couch during a viewing of The O.C., glance at the TV, and then ask, incredulously, whether these people were supposed to be in high school? A quick check of a teen’s phone screen is more complicated, and more challenging. Similarly, my parents used to require that I woke them up to say good night when I got home from a night out. They were often half-asleep, but never, somehow, so asleep that they wouldn’t have been able to smell alcohol or check the clock. The same strategy applied to a night spent “out” on Snapchat is, in most cases, nonsensical.

And yet, the same principles apply. You can’t, or at least you wouldn’t want to, sit with your child through an entire season of The O.C.3. You can’t follow your child around on their night out, squeezing yourself in between their friends in the backseat of the car. You will never be able to monitor everything your child does, nor should you. But you can take steps to monitor more effectively. Even when it comes to their tech use.

How much should I monitor my teen?

The key takeaway of the academic debate around parental monitoring is this: knowing what your kid is up to is important. This goes for online behavior, too. But exactly how this looks varies for each family and each teen.

In my opinion, this is one of the trickiest things to navigate when it comes to teens and tech. When, and how, should you monitor what your teen is doing on their phone or social media? How can you respect your teen’s privacy while also ensuring their safety? Gaining independence is a critical developmental need for teens, which means that more supervision is not necessarily better. As a result, these are really important, and complex, questions. On a scale of 1 to Every Breath You Take, how closely should you be watching?

One useful way to think of this issue is on a spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is total independence for your teen. They might have a phone, they might not. You don’t know. That’s their business. On the other end of the spectrum is Big Brother4. You’re watching their every move, every typed letter, every swipe.

Let’s imagine this spectrum is like one of those “balance beam” scales you see at the doctor’s office, with the slider at the top. You move the slider back and forth until you find a perfect balance, somewhere in the middle of the two extremes. Every teen, when they step on the scale, is going to need a slightly different balance of independence versus supervision. As your kid gets bigger, that slider will need to move to a difference spot—the balance will change. Day to day, you’re not going to see major changes in the position of the slider, but there will be a bit of tinkering, a little bit of flexibility here and there.

Some factors that may tip the balance of the scale:

Age (and maturity). Younger or less mature kids are going to need more supervision, but as teens age, they’re going to need more independence. Going back to the data, we do see differences in monitoring strategy by age. For example, 72% of parents of 13- and 14-year-olds at least sometimes look at their teen’s call records or text messaging history, while only 48% of parents of 15- to 17-year-olds do.

Personal History. Has your teen given you reason to be concerned? Teens who are prone to more rule-breaking and risky behavior in their offline lives are likely going to need more supervision online, too.

Tech Access. If you decide to get your 11-year-old a smartphone and let them download Snapchat, one condition may be that you will be keeping a closer watch. If your 17-year-old uses their phone exclusively for texting close friends and family, you can probably loosen the reins.

So, how do I monitor what my teen is up to?

Okay, so you’re ready to monitor what your teen is up to on their phone. You’re ready to find your family’s perfect balance of supervision versus independence. What should you do?

Let’s go back to the three components of monitoring: teen disclosure, parental supervision, parental solicitation.

In simpler terms: Ask, Look, and Listen.

Here’s how to do each of them.

Ask

Ask frequent questions about what your teen is up to on their phone. You can think about structuring these questions using the 5 W’s:

What are they doing?

Who are they talking to?

Where are they (i.e., which apps, sites)?

When (and how much) are they doing those things, or talking to those people?

Why do they like or dislike doing certain things on their phone?

Of course, some teens are naturally more likely to share, while others are naturally more private. That is okay. The goal is simply to create an environment in which your teen feels comfortable sharing. In the research, this is sometimes called parental warmth, and studies suggest that it is essential to effective monitoring, and to parenting in general.

Some tips to get your teen talking:

Keep it casual. If your kid is sitting at the kitchen counter on their phone, do not drop what you’re doing, sit directly next to them, and stare into their eyes. This is uncomfortable for everyone involved.

Instead, busy yourself with chopping some vegetables, or unloading the dishwasher, and ask, simply, What are you up to? or So, who are you chatting with?

Other good, casual times to strike up conversation: in the car or on a walk.5 One caveat here: do not busy yourself with looking at your own phone. This is a conversation killer.

Approach with interest, not judgement. Teens will immediately sniff out a criticism or concern disguised as a question. This is conveyed in both the words that you say, and the tone that you say it with.

Don’t tell me you’re talking to Andrew again? is very different from Oh you’re talking to Andrew! What does he have to say?

For now, lean into curiosity.

Ask Open-Ended Questions. One of the first things you learn as a therapist to teens is to limit questions that can be answered in a single world, as these make for very long, quiet therapy sessions. These include yes/no questions (Are you on TikTok?), “or” questions (Are you talking to Alex or Meg?), and numerical questions (How many followers do you have?).

Instead, ask open-ended questions like: What kinds of things have you been watching recently? Who are you talking to? How are you liking that game/app?

If you start out with a yes/no question, you can always follow up something open-ended, i.e. You: Are you on Tiktok? Your teen: Yea. You: Oh okay! What are you up to?

Encourage Honesty. Reinforce for your teen that honesty is the best policy. Make it clear that lying to you is a worse offense than just about anything they might be doing online. This will encourage your teen to tell the truth when you ask them questions, giving you a more honest picture of what is going on.6

Be Open. Sometimes, it can work well to lead into a question with a brief disclosure about yourself. You don’t want to take over the conversation, but you do want to make it clear that tricky tech situations come up for everyone, including you.

For example: Earlier today I ran into this situation on Facebook, where two of my friends were arguing about politics in the comments of one of their posts. It got really nasty, and I wasn’t sure whether I should weigh in or stay out of it. Does anything like that ever happen to you? What do you typically do?

You can also share, more generally, about what you’re up to online, who you’re talking to, etc. Do not be discouraged if your teen gently places their forehead on the nearest table and begs you to please stop talking out of boredom.

Listen

Your teen might disclose what they’re up to, good or bad, in response to your questions, or they might do so spontaneously. Either way, you want to be ready to listen effectively.

Here’s how to do it:

Save the teaching moment for later. You have two goals in a listening moment. First, making your teen feel heard. Second, making your teen more likely to disclose again in the future. Sometimes, a moment of disclosure is the perfect segue into a conversation about appropriate online behavior, or an expression of your concerns. But often, that can wait until later. Let’s imagine your teen comes to you, looking upset. They show you a text from a so-called friend. It contains some choice words directed at your teen, as well as some words you’ve never heard before, but which are probably also bad. You also see some texts that your teen sent back, and they, too, contain some language you aren’t thrilled about. It is very tempting, in this moment, to want to teach your child something:

I know [friend] was rude to you, but that language you’re using is not okay.

Or: I don’t want you texting with [friend] anymore.

It will be important to eventually come back to these statements. But in this moment, these responses actually make it less likely that your teen discloses things to you in the future. Instead, respond with validation and lots of follow-up questions. The teaching can come later.

Remember details. When your teen discloses tech-related things to you, do your best to remember them. This is harder than it sounds, particularly when the things they’re sharing are foreign to you (And remind me again why Eric can’t help you defeat the husks in Save the World mode?). But when you do remember, it is a powerful indicator that you are listening and that you care. Check in later about the things your teen shares:

Hey, I remember you saying that there was a new season in Fortnite last week. How are you liking it?7.

Reflect back. This is another tried-and-true therapist skill that works like magic in everyday conversation. When your teen discloses something to you, simply repeat back what you heard. It shows you’re listening closely, and it encourages your teen to continue sharing. This works in conversation with adults, too. Let’s imagine your teen is telling you all about some drama that is unfolding on Snapchat. Sarah posted something rude about Lucy, but didn’t mention Lucy’s name. Then Tommy took a screenshot of the post, and sent it to Lucy. Then Lucy confronted Sarah…etc. All you need to do in this situation is summarize.

Oh wow. So, Sarah posted something rude about Lucy, and then Lucy confronted her when she found out.

Then pause. That’s it.

Most likely, your teen will simply continue sharing. Yea! And then Lucy messaged me, and asked if I had seen the post…

Look

We’ve covered the basics of asking questions and listening to your teens’ responses. The third component of monitoring—and often the trickiest one to navigate—is supervision. This is where you’ll need to think carefully about where you and your teen fall on that spectrum of supervision versus independence.

For some families, “looking” will involve nothing more than a quick glance at your teen’s phone over their shoulder once in a while. For others, it will involve installing apps or software that alert them to concerning content on their teen’s phone. Remember, this will involve considering your child’s age, history, and devices used. You know your child best.

Here are some ways that families might choose to supervise what their teens are doing on their phones, all of which fall somewhere along that spectrum:

Sit with them. Sit near your teen while they’re using their phone. You might require that they use devices only in “public” spaces in the home. Peak over their shoulder once in awhile, ask them to show you what they’re up to, etc.

Co-use. If there’s a video game they love, or an app they’re excited about, or a viral video they’re laughing about, join them. You might learn something, and you might have fun. Alternatively, you might begin to consider pulling out your own hair if you’re forced to watch one more hilarious prank video. Do not do this. Show interest and your teen will be more likely to share their online life with you in the future.

Get a tour. Take co-using a step farther by having your teen give you a “tour” of what they’re up to on their phone. They can show you games, apps, photos, social media posts, etc. Ask questions as you go.

Pair your phones. Family Sharing (on iPhone) and Family Groups (on Android) allow you to set limits on screen time and app downloads on your child’s phone.

Spot checks. Do “spot checks” of your child’s phone or online history. As with all supervision, the fact that you’ll be doing this should be communicated in advance. This is likely to go better if it is done together with your child.

Share passwords. Some families share phone or social media passwords. The upside of this is that it allows access to a child’s phone activities in case of concern. The downside is that it may teach your child that sharing their passwords with others is a good idea. One option: have your child write down their phone password and put it in a sealed envelope on an agreed-upon location in the house. You will only open it in case of emergency (i.e., serious concerns about their safety or health).

Follow them. Follow your child on social media. If you want to keep a closer eye, require that they allow you to follow all of their accounts. If you do not feel comfortable with this arrangement, consider having another adult, or perhaps an older sibling or cousin, follow them to keep an eye.

Get technical. A number of technical tools—apps, software—exist that allow for closer monitoring of kids’ online communication and phone use. These range in terms of their features, everything from alerting parents of concerning social media posts to tracking teens’ location. Here is a list of options.

One important note: you cannot monitor using Look without also using Ask and Listen. Except in the most extreme of circumstances, spying on teens—that is, watching what they’re doing on their phone via technical or other means, without first telling them that you’ll be doing so—is not a good idea. It tends to make teens angry, lose their trust, and encourage sneaky behavior. No matter where you and your teen fall on the spectrum of supervision versus independence, you cannot effectively monitor your teen’s social media behavior without open communication. Have a conversation with your teen before engaging in any kind of direct supervision, where you outline the plan. Provide rationale.

For example: It’s my job as a parent to make sure that you’re safe.

Or: If I have concerns about your health or your safety, I need to be able to check in to make sure you’re okay.

Ideally, you have a plan for monitoring when your child first gets a phone, or maybe when they first get access to social media. But if not, it’s never too late to start. Give your rationale, lay out your plan, and then stick to it. You can always frame it as an experiment:

Let’s try this plan for a month, and then we’ll check back in about how it’s going.

When I began writing this week’s newsletter, I did a quick Google search to see what was out there: “Should I monitor my teen’s phone?” Here is a selection of article titles from just the first page of results:

“Why Parents Should Never Cyber-Snoop or Monitor Their Kids”

“I Monitor My Teens’ Electronics, and You Should Too”

“When you Monitor Your Child’s Phone, You’re Invading My Child’s Privacy”

“Monitoring Your Childs’ Device is a Good Thing. Here’s Why.”

This, I find, is not helpful. A reminder to the Techno Sapiens parent community: navigating your kids’ tech use is hard. It’s frustrating and confusing and Googling it is scary. There will always be, say, 23% of parents who “often” look at their child’s text message history and 20% who “never” do. There will also always be 100% who aren’t quite sure what the right thing is to do for their teen. You can find the right balance for your family. Trust yourself. You’ve got this.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

A wise mentor once told me that the reason the debates in academia are so fierce is that so little is at stake. I think about this at least once a day.

Some argue that “parental control,” or setting rules and enforcing them, is another aspect of monitoring. I certainly agree that this is a critical aspect of parenting teens. However, when and how to set rules is a complex topic, and I only have a week to write these newsletters. So we’re saving that topic for a future post.

Why do I keep bringing up The O.C.? I don’t know. Maybe this show was a more defining feature of my adolescence than I realized? Anyway, here’s another O.C.-related story: I went to a Catholic high school. During the year The O.C. was in its heyday, I also happened to be taking a theology course in which each class began with a group prayer. Students were asked to raise their hands to request special “intentions,” or prayers for themselves or loved ones. One Wednesday morning, a student raised her hand and began requesting prayers for her friend Marissa, who was really struggling in her relationship with this new guy that moved to her town, and also with drinking too much sometimes, and also with her family, because her mom was having an affair with her 17-year-old ex-boyfriend…Our teacher nodded along sympathetically. Let Us Pray, we all chanted.

Quick note that Big Brother, a survivor-like TV show in which contestants (“HouseGuests”) live together and vote each other off each week, debuted on CBS in 2000 and is still on the air. It is currently in its 23rd season. After spending far too long on the Wikipedia page, I still am not sure I understand the rules, but I am thoroughly disturbed. According to Wikipedia: “Beginning with Season 7, the losers of the Have-Not competition were required to eat ‘Big Brother Slop’ for food, and sleep in a special "Have-Not" room with cold showers and most discomforts such as hard pillows and beds for a week…A controversy occurred during Season 21 where eventual winner Jackson Michie also broke the rule, but was not issued a penalty due to the obstruction of the camera view behind the shower walls while eating non-slop.” Oh, also viewers can check out a 24-hour live feed of the inside of the house at anytime, online. I have so many questions.

If you’ve ever been to therapy, you may have noticed that chairs are typically set up at a 90 degree angle to one another, rather than directly facing each other. There is a reason for this. People tend to feel more comfortable communicating when they’re not staring directly at another person’s face. This is another reason that activities like walking or driving, in which both parties are facing the same direction, are good times to strike up a conversation with your teen.

Full disclosure: Encouraging Honesty was a suggestion provided by my mom, whose skills in parental solicitation (and copy-editing newsletters) are truly unmatched.