New Study: Is Hating Facebook Bad For Us?

Whether you think Facebook is bad for you, or you think it’s good for you—you’re right

Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

Summary for Busy Sapiens

New study of 29,284 people across 15 countries, with time spent on Facebook recorded from Facebook servers

Beliefs about whether Facebook is good or bad influenced its effects on well-being

People who believed Facebook was bad for them showed negative effects of use on well-being

People who believed Facebook was good for them showed no effects of use on well-being

I first started studying social media in 2012. In the rare moments that I pried my fingers off my grad school laptop and wandered back into society, friends would ask about my research.

What are you studying? They’d ask, tucking their Blackberries back into the tote bag they received at last weekend’s all-expenses-paid company offsite in the Hamptons. I’d stare at the investment bank logo on the tote bag, suddenly flooded with a memory of my own last weekend—my roommate and I screaming and frantically waving brooms as a giant cockroach scurried across the floor, further evidence of a growing pest problem that neither of us had the time or money to address.

I’d explain that I study the effects of social media on teens’ mental health.

Oh, that’s interesting! They’d respond. What are you finding?

Over the past few years, I’ve noticed this conversation shift. For one, there are no longer Blackberries nor my existential fear of remaining a poor, unskilled woman-child, attending school forever and crying about cockroaches while my friends become successful, well-paid professionals.1

More importantly, though, when I now explain my research, the response is a bit different.

Oh GOD! They say. It’s really bad, right? Social media is ruining our kids’ mental health and everything is terrible.

When I first began studying the mental health effects of social media, whether it was good or bad (or something in-between) was, in my mind, a truly open question. Now, public opinion has shifted. There’s a widespread belief that social media is responsible for all range of social ills, from political polarization to the teen mental health crisis.

I’ve often wondered whether this widespread belief influences the effect that social media actually has on us (and our teens) when we use it. So, I was intrigued by this study, which is the first I’ve seen on this topic.2

What’s the study about?

According to the Internet, Henry Ford once said, “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t—you’re right.”3

With some minor editing, this quote is highly relevant to the study’s hypothesis: “Whether you think Facebook is bad for you, or you think it’s good for you—you’re right.”

The researchers wanted to see whether our beliefs about Facebook’s impact on our well-being play a role in its actual impact on our well-being. Specifically, they tested whether beliefs about Facebook moderate the association between time on Facebook and well-being.

Moderate is an important word in research. It means that a third variable (in this case, beliefs about Facebook) influences the strength or direction of the relationship between two other variables (time on Facebook and well-being).

Here’s a non-research example of moderation:

Earlier this week, I was trying to feed my son pureed prunes while he wiggled around in his high chair.4 In general, there’s a small positive correlation between prune-on-spoon and prune-on-face (i.e., when there’s more prune on the spoon, there’s also more prune on his face).

However, this association is moderated by a third variable: baby wiggling.5 The degree of association between prune-on-spoon and prune-on-face depends on how much the baby is wiggling around. More wiggling means a stronger association between spoon prune and face prune.

What did the researchers do?

In the summer of 2019, the researchers displayed a clickable link on the Facebook News Feeds of hundreds of thousands of people. It read “<Name>, we’d like to hear from you. Please tell us about your experience using Facebook.”

A total of 29,284 people across 15 countries clicked the link and filled out the survey.

The survey had questions about well-being, like “How good do you feel most of the time?”

It also had questions about beliefs about Facebook, like “To what extent do you think Facebook is good or bad for you?”

To get an accurate measure of time spent, the researchers looked at the actual Facebook servers to find each participant’s average daily minutes spent on Facebook during the last 30 days. For comparison, they also asked people to estimate how much time they spend on Facebook on an average day.

Methodological sidenote

Hold on, you may be saying, how exactly did they get that information from Facebook? The answer is that the study was done in collaboration with Meta (formerly known as Facebook). Meta occasionally collaborates with academics, as in this study, through its research programs.

And now, with the knowledge that Facebook was involved in this research, you may be saying is this study legit?

The short answer: I think so. There are, of course, questions about conflicts of interest and Facebook’s internal research protocols, but I do not think these invalidate the study’s findings.

This study went through two rounds of review at Meta.

First, the research plan was reviewed by a five-personal panel. According to the Meta website, this panel is “an extended review group…composed of five experts, with experience across substantive research areas, research ethics, law, and policy,” which weighs research proposals’ risks and benefits.6

Second, the research was reviewed after the study was complete. The authors write, “this manuscript was reviewed by the company prior to publication. No findings were changed in this review.”

Does Meta reviewing research findings to determine their suitability for publication represent a conflict of interest? Of course it does. The risk, obviously, is that only certain research findings (those favorable to Facebook) will see the light of day. However, I don’t think this issue affects the validity of the results for this particular study.

We can still do what we normally would with a single research study—use it as one piece of evidence to inform our thinking, knowing that it’s certainly not the whole story.

Okay, back to the study. So…do people hate Facebook?

In response to the questions about whether Facebook was good or bad for them and society, people rated Facebook a 6.7 out of 10 on average. This is on a scale where 0 = Very Bad, 5 = Neutral, and 10 = Very Good.

This varied, though. Younger users (under age 30) thought Facebook was worse than older users did, and women thought it was worse than men did.

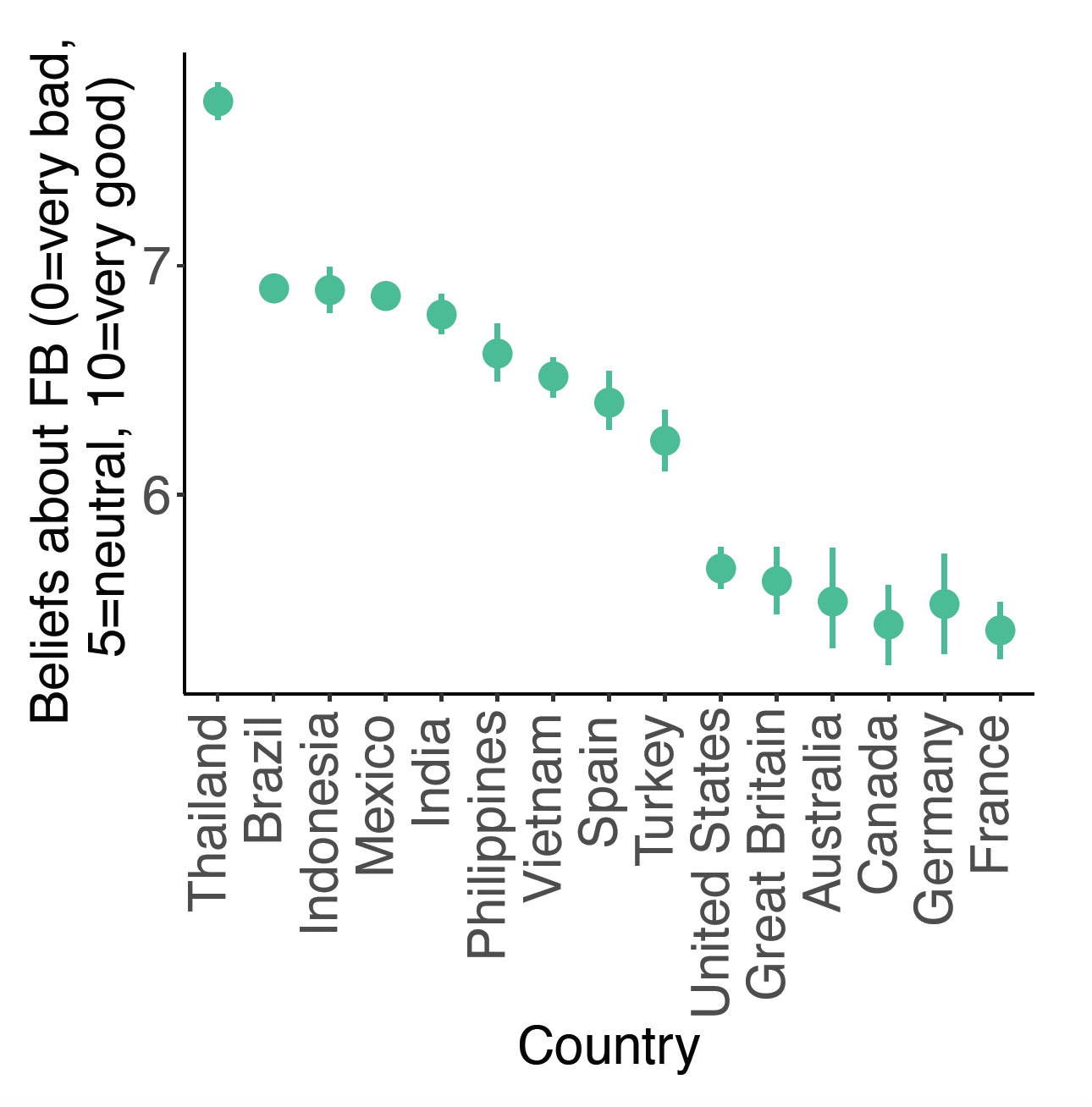

People in the U.S. and Great Britain thought Facebook was worse than those in Brazil and Thailand (especially Thailand—they seem to really love Facebook there). See this graph for the full cross-country breakdown.

And why do these beliefs matter?

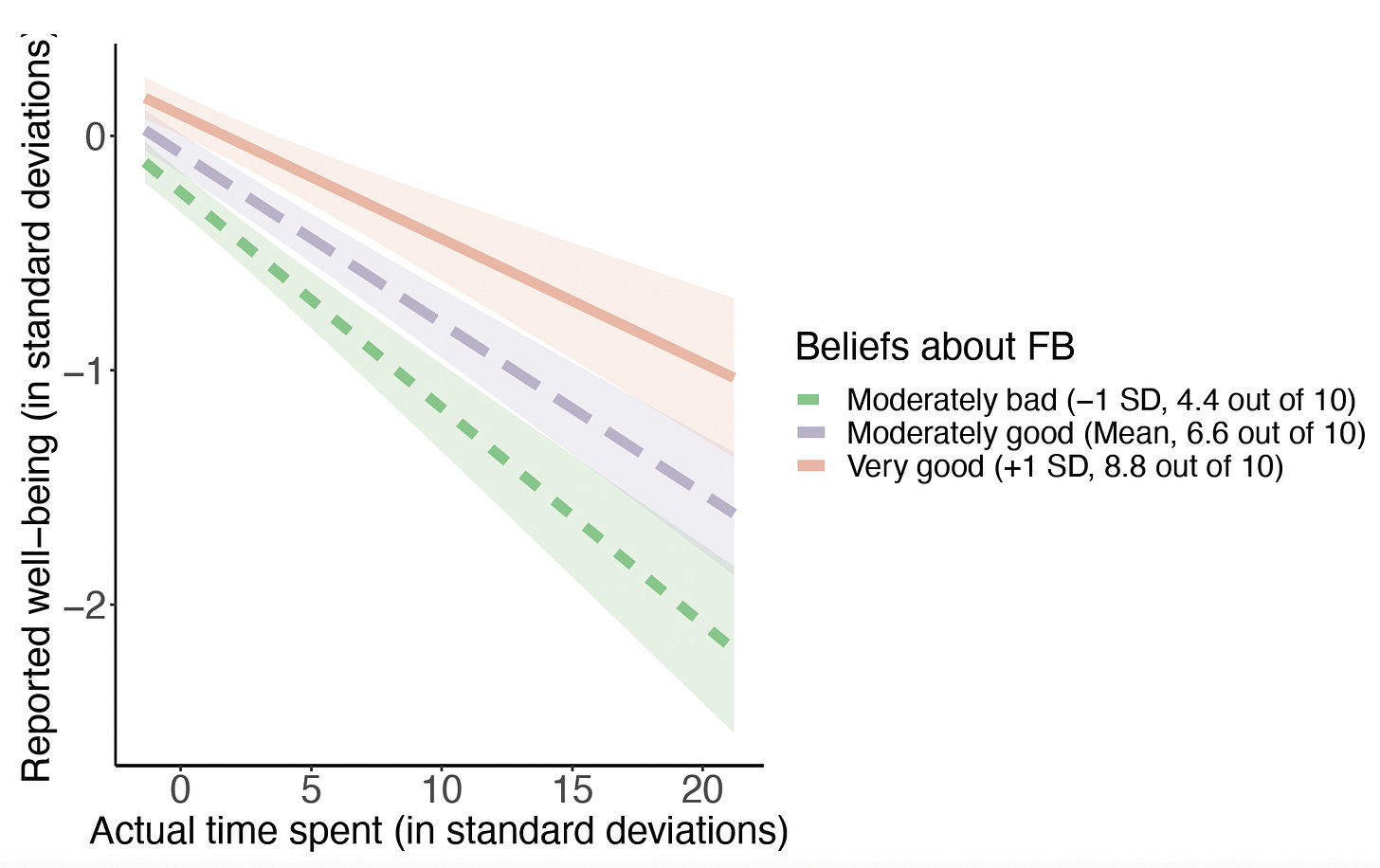

In the end, the authors’ hypothesis was confirmed. The effects of Facebook time on well-being were dependent on how good or bad people thought Facebook was for them.

In fact, beliefs about Facebook had a 2.4x greater impact on well-being than did actual time spent on Facebook.

On average, time spent on Facebook did have a small negative effect on well-being. But if we group people based on their beliefs about Facebook, and then look at this effect, things get interesting.

Let’s take a look at the below visual to illustrate.

The salmon (?)-colored line is for people who thought Facebook was the best for them. For these people, there was no effect of time spent on their self-reported well-being.

The green line is for people who thought Facebook was the worst for them. You can see that the green line is steeper, meaning that for these people, more time on Facebook was associated with worse well-being.

Another way to read this figure: if we look at all the people spending lots of time on Facebook (right side of the figure), those who thought Facebook was bad reported much lower well-being than those who thought it was good.

One other note: remember that the authors also (separately) asked people to self-report on the time they spent on Facebook. The effect of beliefs about Facebook was even stronger when the authors looked at these self-reports, versus the actual time logs. This matters because studies often use self-reported time as their primary measure.

What do these findings NOT mean?

These findings do not mean that the time we spend on social media is irrelevant to our well-being, nor that the negative impacts of social media are somehow “all in our heads.”

They do not mean that we can just will ourselves into believing Facebook is good for us, and then we’ll all be fine.

They also don’t mean we should all move to Thailand, which is, apparently, a magical Facebook-loving place. (We should maybe all move to Thailand for other reasons, but not based on any findings from this study).

The main hangup, in my mind, is the direction of effects. This data was collected at a single time point, so we can’t say which came first—the beliefs about Facebook, the time spent on Facebook, or the well-being.

It’s certainly possible that people spend time on Facebook, have a terrible experience, and then come to believe that Facebook is bad for them. If this is the case, the “beliefs about Facebook” variable would simply be a proxy for actual negative Facebook experiences. Kinda boring.

The more interesting explanation is that people come to believe Facebook is bad for them due to, say, popular press coverage, and then because they believe this, it actually becomes bad for them.

We can’t say which of these possibilities is right from this study alone.

What DO these findings mean?

They mean that we should take a closer look at people’s beliefs about social media—or “mindsets,” as the authors call them—in future studies.

They also mean that we may want to be careful about the messages we convey, to ourselves and our children, about social media. Should we be clear about the downsides of social media, about the very real risks it presents? Of course.

But when the messaging is akin to “no matter what you do, using social media will ruin your mental health,” what mindsets does this create? And if those mindsets play a role in the actual effect that social media has on us, are we setting our kids up to fail when they inevitably log on?

For me, it comes back—as it always does—to balance. To neither demonizing nor dismissing social media. To recognizing its potential benefits, while taking its risks seriously. And maybe, to moving to Thailand.

If I’m being honest, this existential fear is not entirely gone. Also, I still find cockroaches to be very upsetting.

Full citation: Ernala, S. K., Burke, M., Leavitt, A., & Ellison, N. B. (2022). Mindsets Matter: How Beliefs About Facebook Moderate the Association Between Time Spent and Well-Being. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New Orleans, LA, USA.

“Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t—you’re right.” Worth noting that I thought I could write this post at a leisurely pace over the course of a two-week trip visiting family, without staying up far too late to finish it Sunday night. I was not right.

Yes, we do both purees and finger foods. Baby-Led Weaning kind of scares me. However, I am a big fan of this article, which has many adorable videos of babies eating foods of various sizes and textures. I particularly like that each video is labeled with the name of the food and the baby. For example: “Quentin, 11 months, works on a spare rib” and “Zuri, 9 months, munches on a mango pit.”

A moderator is a third variable that influences the strength or direction of a relationship between two other variables. In the prune-feeding example, baby wiggling is the moderator. A mediator is a variable that explains the relationship between two variables. A mediator of the relationship between prune-on-spoon and prune-on-face would be spoon-on-cheek (instead of in mouth).

Normally, research involving human subjects happens at institutions like universities, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. When it does, it has to be approved and monitored by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). There are specific federal requirements for IRBs, such as who should be on them and how they should be registered with the FDA. There are no federal rules requiring Facebook’s internal research to fall under the purview of an IRB. So, this review committee is an (optional) step Meta seems to have taken to review its research protocols. Is this expert committee the ideal solution for evaluating the safety and ethics of Facebook’s research studies? Probably not. But whether IRB review should be required for studies conducted by Meta and other tech companies is a question for another day.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst