Are screen time limits backfiring?

New study suggests we've been doing screen time limits all wrong

Hi! I’m Jacqueline Nesi, a clinical psychologist, professor at Brown University, and mom of two young kids. Here at Techno Sapiens, I share the latest research on psychology, technology, and parenting, plus practical tips for living and parenting in the digital age. If you haven’t already, subscribe to join nearly 20,000 readers, and if you like what you’re reading, please consider sharing Techno Sapiens with a friend.

6 min read

It’s the middle of summer. The kids are bored. You’re bored. The whole family has turned into an army of TikTok-scrolling, Netflix-binging, Prime Day deal-shopping zombies. Screen time has spiraled. You’ve decided it’s time to take back control.

You’ve heard it’s a good idea to set screen time limits. So, you take a moment to think it through. What’s the maximum amount of time you’d want your kid, or yourself, to spend on TikTok each day? You pick a time limit, adjust the settings, and there you have it! A recipe for health, happiness, and, of course, reduced screen time…right?

Maybe not.

A new study is out titled Does setting a time limit affect time spent?,1 and now I’m questioning everything. Do time limits work? When and how should we set them? Do I actually need that portable neck fan2 from Amazon (but it’s Prime Day!)?

Let’s dive in.

What’s all this about?

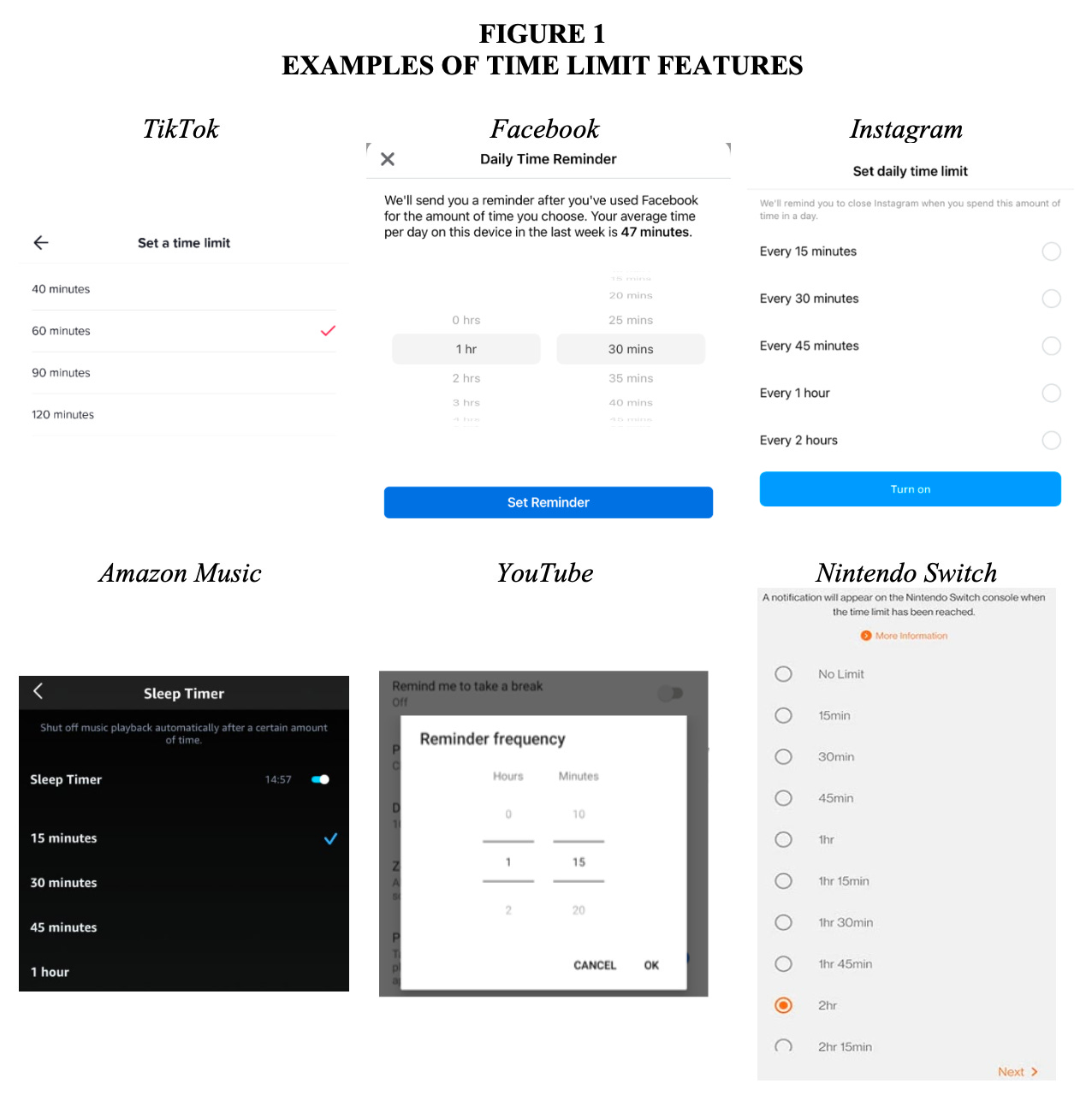

Screen time limits, for ourselves and/or our kids, are generally thought to be a good thing. We’re encouraged to set them via either in-app social media tools, or via our devices’ Screen Time function, and when the limit is reached, a friendly little reminder pops up to tell us it’s time to log off (or ignore it).

So, with this study, researchers at the University of Delaware and Duke set out to answer a simple question: do they work? Do time limits actually reduce the amount of time we end up spending?

This study was incredibly thorough. The researchers ran—I kid you not—10 different experiments3 to test this question. I know we’re all busy testing out Threads and whatnot, so we’ll just hit the highlights.

What did the researchers do?

First, the researchers did a “field experiment,” in which participants were out in the “real world,” using their own devices.

Nearly 300 adult participants were assigned to use TikTok for two days.

Then, all participants were told to set a time limit using TikTok’s native “Digital Wellbeing” tool, and to use TikTok for two more days.

They reported on how much time they spent on TikTok before and after setting the limits. They got this information from their phones’ “Screen Time” app, to ensure accuracy.4

Then, the researchers did a series of “controlled experiments,” some of which were in a physical lab and some of which were online.

Over 3,000 adults total participated in these experiments.

In each experiment, participants were given 5-6 minutes to split between two activities.

One activity was fun, like Pinterest browsing or playing a game

One was not-so-fun, like transcribing boring text (for pay, to ensure they had some actual incentive to do it).

Some participants were randomly assigned to set limits on the “fun activity” time (experimental condition), and some were not (control condition).

Participants in the experimental condition saw a prompt like this: “To help you manage your time during the study, please set a time limit reminder to appear after you have spent a certain amount of time on the Pinterest Activity…This reminder will pop up and let you know when you have spent this amount of time on the activity.”

These participants were given options for time limits that ranged, across experiments, from 15 seconds to 5-6 minutes (i.e., no limit)

Researchers then measured how long participants in the different conditions spent doing each activity.

So, what did they find?

Across nearly all experiments and all conditions, time limits made no difference. In fact, in most cases, setting a time limit actually increased the amount of time people spent doing the “fun” activity. In other words, time limits backfired.

This held true whether the time limit options were given in 15-second or 1-minute increments.

It held true whether the time limit was suggested (i.e., please set a time limit) versus required (i.e., we have set a time limit for you).5

It held true even though participants were actively losing money by spending more time on the fun activity (Pinterest) at the expense of the not-so-fun activity (transcribing text for pay).

And if you’re thinking okay, fine, but I would never do that…I have bad news. In one experiment, 51% of people believed the limits were working (i.e., causing them to spend less time), and 40% of them thought they had no impact. Only 8% accurately reported that the limits were causing them to spend more time. In other words, we’re pretty bad at assessing how well time limits are working for us.

But why?! How is this possible?

The answer is a concept called budgeting. To illustrate how this works outside of time limits, let’s take an obvious example: money. Imagine, hypothetically, that you’re a graduate student doing some kind of menial labor, like, say, teaching an upper-level college course and shaping the young minds of our country’s future workforce. You earn roughly 15 cents per hour.6 As such, you decide you need to stop spending money on frivolous items, so you budget your earnings, setting a limit of, say, $10 per month on coffee from Carroboro, North Carolina’s Open Eye Cafe.

It turns out, the literature on budgeting suggests that this $10-per-month limit can actually cause you to spend more on coffee. The reason is that you’ve now earmarked $10 per month as the amount you have available for coffee. Now, you feel totally fine about spending that $10, and if you haven’t yet reached that month’s coffee quota, you’ll happily go out and spend it.7

The current study shows that the same principle carries over to the ways we “budget” our time.

In one experiment, the researchers found that when participants set a screen time limit, and subsequently spent more time browsing Pinterest, this was partially explained by how much time they perceived was available or earmarked for Pinterest browsing (i.e., “how much time did you feel free to spend on the Pinterest activity?”). And in another experiment, they showed that participants viewed incremental time spent on Pinterest more positively when it fell below the limit they had set (versus when there was no limit).

Well, shoot.

But wait, there’s still hope!

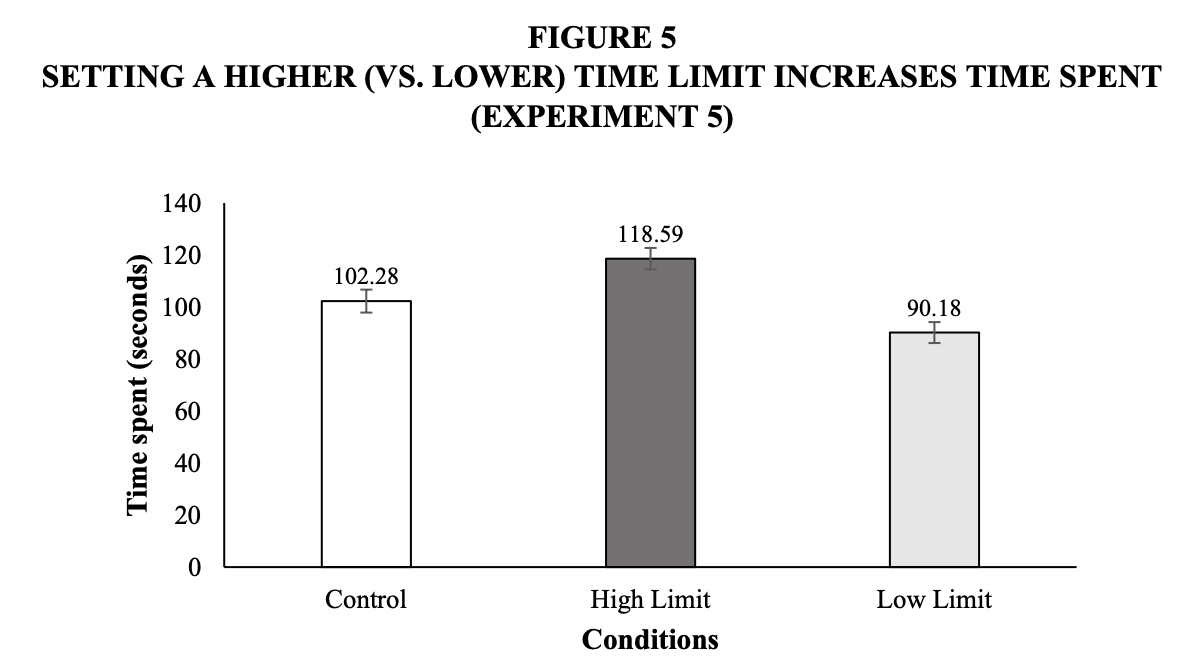

There was one exception to the limits-increasing-time-spent pattern seen consistently across experiments, and that was this: very low limits. When participants picked the lowest possible option for time spent (e.g., only 15 seconds allowed on Pinterest during the 5-minute task), the limits worked. They spent less time overall.

So, in a final swan song of an experiment, the researchers tested this directly, randomly assigning some participants to choose a high time limit (3-4 minutes), some to a low time limit (10-40 seconds), and some to no limit.

Participants in the “low limit” condition did, in fact, spend less time than those in the control group, who had no limit. Hurrah!

Mistakes, I’ve made a few

It seems we’ve been approaching screen time limits all wrong. When we go to set a limit, we often start by asking ourselves the maximum amount of time we’d be willing to spend (or have our kids spend) on an app or device. This, paradoxically, may be increasing the amount of time we spend on our screens—even though most of us mistakenly believe our limits are working.

This study tells us that, instead, we should try setting a limit much lower than we might think (and, certainly, lower than the amount of time we’re currently spending).

Interestingly, this also means we’ll need to be careful about the “default options” that apps provide us for time limits. We can easily get anchored too high. In this study’s TikTok experiment, a mere 29% of participants chose the lowest possible option for TikTok limits (40 minutes per day)—yet these were the only people who actually benefited from the limits they set.

How to do screen time limits right

Choose a number that’s lower than your (or your child’s) current use

Don’t be fooled by an app’s default options

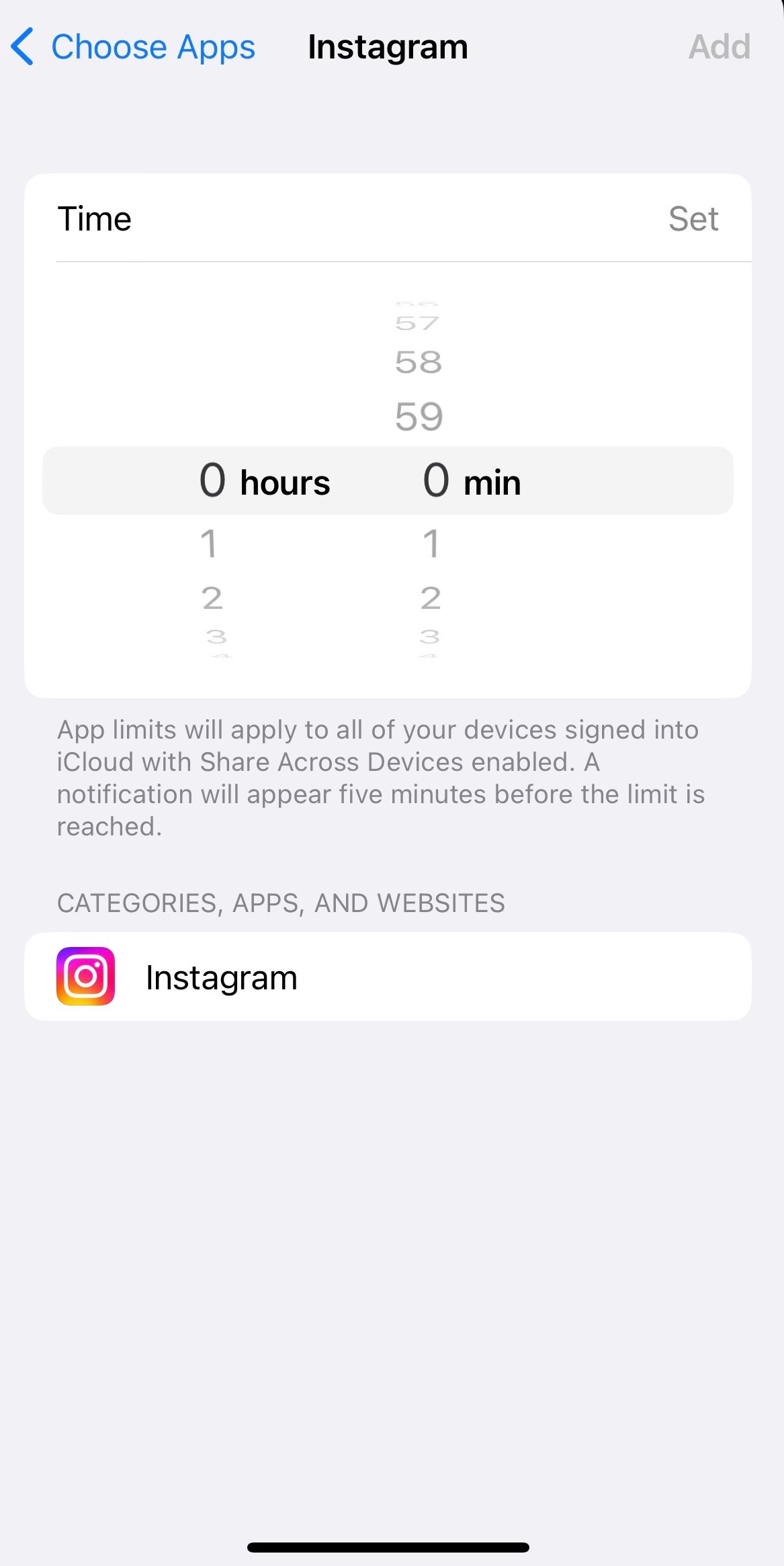

Use the Screen Time function (for iPhone) or Digital Wellbeing (for Android) to set limits, rather than in-app options (e.g., on TikTok) to provide maximum flexibility

Experiment with apps that create “hard limits” (i.e., with no option to ignore)—but avoid the temptation to set higher limits for fear of being “cut off.”

For social media companies: offer lower time limit options, and set default limits lower than a person’s average usage time

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

Silverman, J., Srna, S., & Etkin, J. (2023). Does Setting a Time Limit Affect Time Spent? Available at SSRN. Note that this study is still a “pre-print,” meaning that it’s currently under peer review and hasn’t yet been published in a scientific journal. However, all methods and analyses were “pre-registered” (i.e., made publicly accessible online) before the paper was written, so it is highly unlikely that the results will change after peer review. If they do, I will let you know (and then I’ll really start questioning everything).

I am strongly considering a portable neck fan [a phrase which, when back-translated from my ancestors’ native Italian, I believe means loosely “I have very few friends.”] The AC in our car recently broke in the midst of a multi-hour, traffic-heavy trip home. Our solution involved stopping at a gas station, filling Ziploc bags with ice, and draping them over our bodies for the remainder of the car ride. Surely a portable neck fan would have been more effective (and fashion-forward)?

How the authors managed to do this many experiments for a single paper is beyond me. They technically split them into 5 “main” experiments and 5 “supplemental” experiments, but it seemed like every time I had a lingering question or doubt (e.g., but what if you assigned people to a limit, instead of just suggesting it? But what if you gave a different set of time limit options? etc.), a new experiment suddenly popped up to answer it. There were so many experiments that the authors were just casually mentioning new ones for the first time in the last few paragraphs of the paper! This never happens. It would be like if you went to a delicious, multi-course dinner and then, as you were paying the check, the chef just happened to pop by your table with another full entrée that you never ordered and wasn’t even on the menu? Very impressive, but also, how?!

Interestingly, in the TikTok “field study,” the largest share of participants (45%) chose the 60-minute time limit, even though most of them were spending way less time than that on average. Also interesting is that one participant reduced their time spent by almost 4 hours after setting a limit. A good reminder that different time limits are going to work for different people, depending on their usual use. Not that I want to force yet another experiment on these (I assume) very tired researchers, but I’d love to see a study looking at exactly how much lower than a person’s average time spent the limit needs to be to work (5% less? 50% less?).

Worth noting that TikTok has a “default” time limit for younger users of 60 minutes. For kids who might otherwise have been inclined to spend less time than that, this limit is likely backfiring.

Alright, it was slightly more than 15 cents an hour…but not much. And certainly not enough to hire an exterminator to remove the cockroaches from my North Carolina apartment, where I, afraid to kill them myself, would instead trap them under empty Tupperware containers and bowls, and hope vaguely that they would somehow disappear, only to surprise and horrify my boyfriend-now-husband when he came to visit and found the floor dotted with upside-down kitchen storage items. Ah, memories.

Here’s another (coffee-related) example of the pitfalls of “budgeting.” Since I’m currently pregnant, I’ve been told to limit my coffee consumption (boo!). I decided to set a limit for myself of one cup per day. As a result, my “one cup a day” has become an increasingly large and elaborate monstrosity of cold brew, syrups, special milks, etc. that almost certainly contains more caffeine than I was having prior to this so-called limit. When I drink this, I feel totally fine about it. And on the rare days that I just have a small, simple cup at home (i.e., below my “budget”), I feel like some kind of holistic wellness guru.

I wonder if there's any connection with the way that restricting eating can cause bingeing?

So helpful - will need to experiment with setting much lower limits. Thanks for sharing!