How to use your phone less

11 science-backed strategies to reduce your screen time

Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

A few weeks ago, my husband decided he wanted to spend less time on his phone. He deleted a number of apps, blocked time-wasting websites, and set a new screen time goal. His plan has been, to say the least, extremely effective.

I’ll often look over to find him on the couch doing strange things like reading books. His screen time will top out at an astonishing one hour.1 Did you see, I’ll ask, barely glancing up from my own screen, that Khloe and Tristan are having another baby? He, of course, did not.

At this point, he’s gone off the deep end, saying totally insane things like I probably don’t need Twitter or Instagram on my phone and I think I’ll just leave my phone at home. Can you believe this guy?!

Anyway, the whole ordeal has caused me to start rethinking my own phone use habits, and to be fair, they probably need a reboot.

But changing behaviors is hard! This is especially true for habitual behaviors, the ones that we do everyday, often without thinking. And it certainly doesn’t help that our phones are designed—with their bright red notifications and their slot machine pull-to-refreshes and their frictionless unlocking via facial recognition—to hook us in and keep us coming back.

Luckily, there’s an entire body of science on how to change our behaviors. And today, in a totally selfish, mildly passive aggressive effort to match my husband’s new screen time habits, we’re going to talk about that science.

Behavior change techniques: A (very short) primer

Allow me to present to you: the Taxonomy of Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs).2

Led by Susan Michie, a brave and presumably very detail-oriented scientist at University College London, the taxonomy is a list of techniques for changing behaviors. Michie and co—God bless them—analyzed thousands of interventions targeting everything from smoking to dieting, and distilled them down into their “active ingredients,” or the strategies that actually helped people change their behaviors.3

Now, the taxonomy includes 93 specific behavior change techniques, with everything from “goal setting” to “positive self-talk,” and it gives us a good starting place for how to change one specific behavior: using our phones too much.

We don’t (yet) have many studies telling us which of these BCTS are most effective for reducing phone use, but we do have some hints from other meta-analyses of more commonly studied behaviors like smoking, drinking, and physical activity.4

So, let’s get to it!

11 Science-Backed Strategies to Use Your Phone Less

Strategy #1: Restructure the physical environment

Most of the strategies we’ll discuss below are individual strategies. They involve goal setting, planning, and internal motivation, and they are an important part of changing any behavior.

But before we get to the individual strategies, I want to start with a different type of strategy: those that focus on the environment. This suite of strategies goes by many names: situational self-control (Angela Duckworth), a focus on systems over goals (James Clear), nudges and choice architecture (Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein), but the basic idea is the same: we can shape our environments to increase desired behaviors and reduce unwanted ones.

When it comes to reducing phone use, environment-focused strategies are essential.

According to the BCT taxonomy, restructuring the physical environment might involve:

Avoiding or reducing exposure to cues for the behavior (e.g., putting your phone away in a cabinet where you can’t see it)

Restructuring the social environment (e.g., spending less time sitting amongst friends who are all on their phones)

Adding objects to the environment (e.g., a crossword puzzle book readily accessible to replace phone use).

We can also think of our phone screens themselves as physical environments that we can reshape to our advantage. By strategically adding friction to our phone use experience, we can become more mindful of our use and less likely to instinctively scroll.

My husband, for example, achieved his screen time reduction success by deleting frequently-used apps from his phone, as well as blocking time-wasting websites. And a recent randomized controlled trial of these “nudge-based” phone interventions found that they were, in fact, effective in reducing individuals’ screen time.

Here’s a list of environment-focused interventions you might try to “nudge” yourself to reduce phone use:

Disable notifications

Keep your phone on silent and face-down

Keep your phone out of reach and/or out of sight

Charge your phone outside of the bedroom at night

Disable Touch ID (i.e., use a password instead)

Put your phone on grayscale

Delete frequently-used apps

Rearrange apps on your home screen

Block frequently-used websites

Put phone on Do Not Disturb or Downtime

Strategy #2: Goal Setting

Set a goal for the behavior you want to achieve.

You want it to be specific, rather than general. You want it to be challenging enough that it feels different from your day-to-day, but not so tough that it’s totally out of reach. And you want it to be measurable.

Example: My goal is to put my phone away for the evening, starting at dinnertime everyday.

Alternate example: My goal is to use my phone for less than 90 minutes per day.

[Note: “use phone less,” even if that’s our ultimate goal, is not specific or measurable enough.]

Strategy #3: Problem Solving

Proactively identify potential barriers and ways you will overcome them.

Example: A potential barrier is that I will feel tired and unmotivated at the end of the day. When this happens, I’ll have a substitute activity ready (like reading a book), instead of reaching to scroll.

This also includes “relapse prevention,” or actively planning for the possibility that you will not accomplish the goal 100% of the time.

Example: When I accidentally start looking at my phone after dinner, I will remind myself of my goal, plug it into the charger, and walk away.

Strategy #4: Action Planning

Make a plan for when, where, and how you will accomplish your goal.

This is sometimes called setting an “implementation intention.” There is good evidence that this works. Also, the scientist who’s led much of this work was a professor of mine in grad school, and he’s an absolutely delightful British man. So, I’m inclined to trust him.

The basic formula is simple: create an “if-then” plan. If I encounter X situation, then I will do Y behavior. This allows us to identify the exact situation (the when and where) in which we’ll engage in our goal-directed behavior (the how).

Example: If I sit down to dinner, then I will plug my phone into the charging station for the rest of the evening.

Strategy #5: Self-Monitoring

Have a plan to monitor and record the behavior you want to change.

First, we need to understand when and how often we engage in the unwanted behavior. This can be a surprising powerful step, as studies suggest that simply monitoring our behavior can lead us to change it.

Example: I will monitor my past-week phone use by looking at the Screen Time app on my phone.

[Note: I highly recommend that you do this if you want to be shocked, slightly horrified, and (hopefully) motivated to change. Go to Settings>Screen Time>See All Activity. No, I will not share mine, because I am ashamed.]

After we put our plan in place, we also need to monitor whether it’s working. We can do it the old-fashioned way—writing it down in a calendar or notebook, for example—or we can go digital, relying on the Screen Time (iPhone) or Digital Well-Being (Android) apps on our phones. A digital solution can be particularly useful if our goal is a bit harder to track (like number of phone minutes per day).

Example: Each day that I don’t use my phone after dinner, I’ll mark it on my calendar.

Strategy #6: Social Support

Gather social support toward accomplishing your goal.

The taxonomy breaks down social support into categories: Practical (i.e., our husband gently reminds us about the put-away-the-phone plan), Emotional (i.e., our husband tells us we’re doing a great job with our put-away-the-phone plan), or Unspecified (i.e., our husband acts as a “buddy” in developing his own put-away-the-phone plan).

A recent meta-analysis suggests that goal setting is more effective when done publicly or with a group, so we can also use this to our advantage (brave techno sapiens may wish to use the Comments section below).

Example: My husband and I will both set goals to reduce our phone time, and I’ll tell all the techno sapiens about my phone use plan.

Strategy #7: Social Comparison

Make yourself aware of others’ performance, and compare it to your own.

This is helpful if the comparison motivates you to match others’ behavior more closely. So, you might take a look at your friends’, family’s, or partner’s screen time and compare it to your own, perhaps sparking a little friendly competition.

Example: Knowing that my husband’s phone use time is lower than my own, I’ll take a look at his stats and compare mine. Then, I’ll put all these strategies in place and destroy him in a ruthless competition he didn’t know he was participating in.

Strategy #8: Behavior Substitution

Have a desired or neutral behavior ready to go to replace the unwanted behavior.

Example: I will replace my unwanted behavior (picking up phone) with neutral or desired behaviors (crossword puzzles, high-fiving the baby).

It’s helpful to plan this in advance, removing any friction that might come between you and your replacement behavior (see Restructure Physical Environment, below). The more frequently you repeat an alternate behavior, the more it will become a new habit.

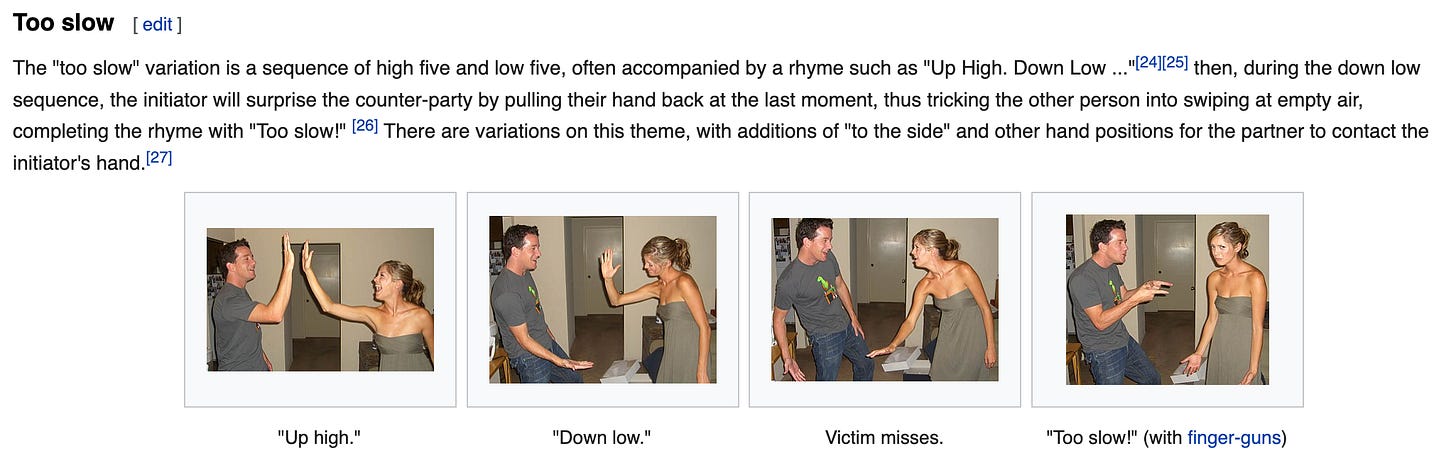

Example: I will have a crossword puzzle book and pencil readily accessible near the couch. I will also research variations of the “too slow” high-five sequence in advance, so that I (and the baby) can be prepared.

Strategy #9: Graded Tasks

Contrary to my initial assumption—likely the result of too many years in school—this does not involve giving yourself a grade on how well you change your behavior. “Graded” here means gradually increasing in difficulty.

So, start with something extremely easy and achievable, and gradually increase the difficulty until you reach your ultimate goal.

Example: If my goal is to stop using my phone in the evenings, I could start by putting my phone down 15 minutes before bed. Every day or two, after achieving the previous day’s goal, I could then start phone-free time 15 minutes earlier.

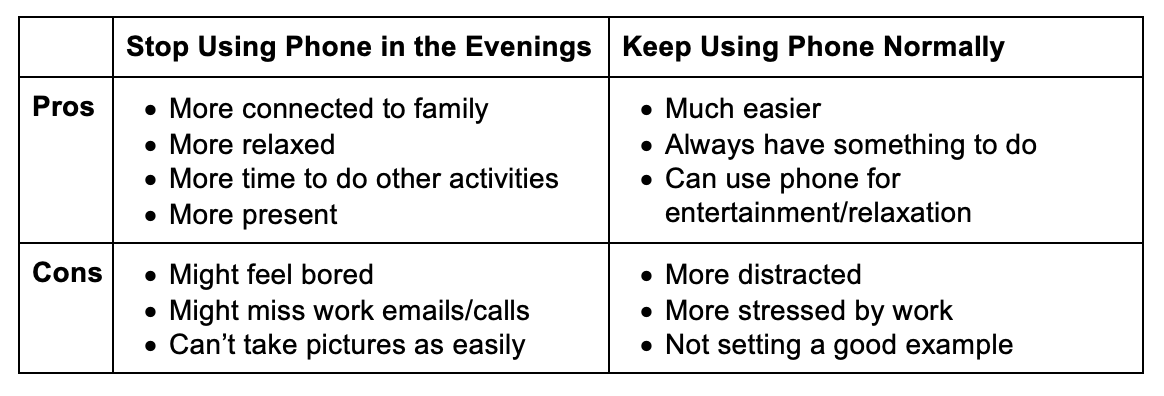

Strategy #10: Pros and Cons

Make a list of advantages and disadvantages of changing or not changing the behavior (also called a “decisional balance”).

This sounds unnecessary, I know. But by making ourselves aware—in advance, and in painstaking detail—of the pros and cons of a behavior, we’re better able to make decisions about that behavior in the moment.

Note: there’s a tendency here to dismiss the pros of an unwanted behavior. There’s nothing good about this behavior! we think, that’s why I want to change it! But for this technique to be successful, we need to recognize the reasons why we might be doing the behavior in the first place.

Example: A decisional balance for reducing phone use in the evenings.

Strategy #11: Self-Reward

Give yourself a reward if (and only if) you stick to your desired behavior change.

The taxonomy notes that rewards can be Material (i.e., a new crossword puzzle book), Social (i.e., a friend congratulates you on your minimal phone use), or Non-Specific (i.e., you go on a celebratory phone-free date night with your husband).

Example: If I stick to my phone-free plan for two weeks, I’ll get myself a new crossword puzzle book.5

Further Reading

The full taxonomy of 93 Behavior Change Techniques can be downloaded here. And it’s also an app!

For more ideas on nudges, as well as apps to block distractions (e.g., Freedom), see this list from the Center for Humane Tech

Atomic Habits by James Clear offers a comprehensive guide to habit change

WOOP (Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan) is a useful system for goal-setting

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

For a nice kick in the pants this Monday morning, I highly recommend you check out your recent screen time. You can do this on iPhone by going to Settings>Screen Time>See All Activity, and on Android via Settings>Digital Wellbeing & Parent Controls

Before the Taxonomy of Behavior Change Techniques, interventions to help people change behaviors like quitting smoking, or increasing physical activity, were extremely difficult to replicate. Scientists would run randomized controlled trials, and if they worked, we’d have no idea why. It was the wild west out there.

Then, Michie and co came along. They endured an extremely rigorous, multi-year process to identify the “active ingredients” of these interventions. I assume this involved a lot of blood, sweat, and tears (though I also imagine they had some very effective behavioral strategies for getting the project done).

Now, we can look at a 12-week weight loss program, for example, and figure out—was it the daily monitoring of steps (BCT #2.3 “self-monitoring of behavior”) that made a difference? Or the weekly review of weight loss progress with a coach (BCT #1.5 “review behavior goals”)? Then, we can take the most effective pieces of that program and use them in future interventions. Thank you, Michie and co.

An analogy for thinking about behavior change techniques as the “active ingredients” of an intervention: I am a big proponent of eating dessert every night. I used to eat a lot of chocolate chip cookies. Then, at some point, I realized that the “active ingredient” in the chocolate chip cookies—the thing that really made a difference in terms of satisfying my dessert craving—was the chocolate. The rest of the ingredients, though delicious, were unnecessary. Now, I eat a lot of bowls of plain chocolate chips.

[Note: I’m told some people enjoy desserts involving fruit, gummy candy, and/or things with the word “sour” in them. I do not understand this.]

Note that nearly all meta-analyses of behavior change techniques find that interventions incorporating more BCTs tend to work better than those with less. So, no matter which strategies you pick in your efforts to reduce phone use, it makes sense to try out a few of them simultaneously.

I hesitate to include mention of my excitement about a new crossword puzzle book because even I can recognize how nerdy this is. But I’ve decided this is a safe space, techno sapiens, and I have all of you to thank for that. Also, if you, too, like crosswords and other puzzles, highly recommend my current read: The Puzzler by A.J. Jacobs.

This is a great read, thank you!! I often feel like I am constantly on my phone because of a need (whether real or perceived) to be accessible for work. Reading this reminds me that that’s very much an excuse to justify my screen time, and that I can always delete apps or use other tools to work around that. Thanks!

I need to save this to revisit frequently! So useful!