How to do discipline

A deep dive on evidence-based discipline for toddlers to teens

Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

Summary for busy sapiens

When we think of discipline, we often think of punishment, and it sounds cold and scary. But discipline is actually a larger system for teaching kids acceptable behavior through warmth, structure, and appropriate consequences.

Warmth means showing our kids we care, structure means setting clear rules and expectations, and consequences are the ways we respond to kids’ behaviors.

Operant Conditioning is a psychology theory that explains how we can use consequences to increase “okay” behaviors and decrease “not okay” behaviors.

15 min read

While in graduate school, I was a therapist in a clinic for families who were struggling with their children’s behavior. Parents would come to the clinic with their young children (ages 3 to 7), and we would guide them through a treatment called “Behavioral Parenting Training” (BPT)1. The goal of BPT is to help parents manage their kids’ behavior and improve the parent-child relationship. It’s often prescribed for families of kids with ADHD or a disruptive behavior disorder.

In the clinic, we would work with parents and children together in a series of highly-structured treatment sessions. There was a lot of teaching and “live” practice of parenting skills. For example: “attending” to a child’s behavior by narrating what they were doing (Oh wow, Sarah, I see you’re putting the red block on top of the green block! And now you’re throwing it in the air!) and giving simple, clear instructions (Sarah, please put the green block into the basket).

There was also—how shall I put this?—total chaos. There were kids stripping down naked. Kids scaling the cinder block walls. Kids peeing on floors, turning off lights, knocking over tables, and—in one instance—gleefully running out the front door of the building and beelining for a nearby park. A child once pulled so hard on my shirt that it ripped. Another picked their nose and stuffed the offending finger into a fellow therapist’s mouth. In a fit of anger, a child once looked at me, dead-eyed, and spat out You smell like cashews.

As graduate student therapists2, we’d find ourselves in these sessions, sitting on a scratchy carpet while dripping sweat in the North Carolina heat, a princess crown haphazardly balanced on our heads, while a four-year-old screamed that they hate us—and we’d wonder: how, exactly, did I end up here?

And yet, it worked. Behavioral Parent Training is very effective for many families. In that clinic, children’s behavior significantly improved, parents reported feeling calmer and more confident, and grad student therapists slowly recovered from repeated punches to the kneecap.

So, what’s so effective about it?

That, techno sapiens, is the subject of this week’s (two!) posts.

Today, we’ll talk about the research-backed principles of discipline that form the basis of approaches like Behavioral Parent Training. As it turns out, these principles are remarkably similar whether you’re dealing with a toddler, a teen, or a kid in between.

Later this week, we’ll be back to apply these principles to a very specific question: should you take away your kid’s phone as punishment?

So, grab your green blocks, strap on your princess crowns, and try to put that comment about cashews behind you (but really, why so specific?)

Let’s talk about discipline.

Wait, discipline? Isn’t discipline bad?

When we think of the word “discipline,” the first thing that comes to mind is often punishments. Having been raised in a Catholic family, the first thing that comes to mind for me, specifically, is my parents’ childhood memories of nuns hitting their students with rulers. Don’t ask me why.

But when we talk about discipline here, we’re referring to your entire system of teaching kids about acceptable behavior. We’re talking about the many, healthy strategies parents can use to increase kids’ “okay” behaviors and decrease their “not okay” behaviors.

There are three main components to an effective discipline3 system:

Warmth: Show you care

Structure: Set the rules

Consequences: Respond to behaviors effectively

We’ll take each of these in turn, spending most of our time on “consequences” because, well, there’s a lot to unpack there.

Before we get into it, it’s worth mentioning: discipline is a complicated topic, and families will have different ideas about what feels comfortable for them. That’s okay! As with much of parenting, it’s very easy to read and write about these topics, and very difficult to actually put them into practice when your child is screaming about Cocomelon. I hope this post will give you some new ways of thinking about discipline, but, as always, you know best what works for your family.

Warmth and Structure: Filling the car up with gas

Let’s imagine parenting is a road trip, where the end destination is one or more kind, happy, and well-adjusted kids. Sure, you could just put some good and bad consequences in place—take away a phone here, give a high-five there—just as you could hop in the car, floor the gas pedal, and start turning the steering wheel at random.

But even if you do a great job turning that wheel—even if you flawlessly execute those consequences—it’s not going to get you anywhere without some underlying fundamentals. You need a map to tell you where to go. You need snacks (peanut M&M’s, specifically). And, if you want this thing to work, you need to fill the car with gas.

In the case of parenting, these fundamentals are warmth and structure. And you need both of them to make it work.

There’s a lot of evidence that these are some of the most important elements to effective parenting.

So, what are they?

Warmth: Show you care

Despite earlier references to the sweatiness of those BPT sessions, warmth does not refer to actual temperature. Rather, it simply means showing your child affection and support. Making it clear that you love and accept them. Showing you care.

For young kids, this may involve anything from play, to hugs and kisses, to saying “I love you,” to watching a TV show together. In the case of the BPT clinic, one aspect of “warmth” was just 10 minutes per day of special, one-on-one positive play time for parent and child.

For older kids, warmth may involve some of the same—though the special time might involve fewer legos and more snack runs, movie nights, or co-created TikToks. It could also involve telling your child one thing you love about them, or thanking them for something they’ve done.

I once worked with a family in which a parent and teen were constantly fighting. Every session escalated into a bitter negotiation between them, with various insults sprinkled throughout. One of our most effective interventions? The pair went out to dinner together.

It can be easy in the rush of daily life, and in the midst of so many don’t do that!’s and what were you thinking?’s, to forget how important these small moments can be.

Think of these moments as deposits in the bank. The more you can establish a positive, loving relationship with your child, the more trust and affection you’ve built up, the more effective other (less pleasant) strategies will be when you need them.

Structure: Set the rules

Structure refers to having consistent, predictable limits, rules, and expectations.

We’ll talk more about how and when to set rules around tech in a future post, but a few basic ideas to keep in mind:

Communicate regularly and openly about your rules and expectations. You can do this in an age-appropriate way from the time kids are young. Whenever possible, explain your reasoning.

Try to be as clear and consistent as possible with the limits and rules that you set. Compare: You can play Minecraft later. vs. You can play Minecraft for 30 minutes on weekdays after you finish your homework, as long as it is before 8pm. [The second one is clearer.]

Be open to adjusting rules to allow more freedom or privileges as kids get older. A good mantra: firm but flexible.

For older kids, actively involve them in developing rules and limits. You might ask them what they think is a reasonable rule for a given situation—sometimes kids turn out to be stricter than parents expect.

Try to differentiate, for yourself, between what’s an absolute no (e.g., playing with the stove; hitting) and what’s a preferred no (e.g., repeatedly singing I’ve been working on the railroad, but replacing all the lyrics with meow’s)4. The absolute no’s are where your rules should be. Try to let go of some of the other stuff.

No matter their age, but especially in the toddler and teen years, kids push boundaries. This is normal and, actually, very healthy. This is how they learn about the world and gradually become independent people who no longer need you to slice their grapes5 and pick them up from soccer practice.

They need freedom to explore and make mistakes, but they do need boundaries—rules and limits—to help them learn.

Consequences: Respond to behavior effectively

Okay, so you’re showing you care and you’ve set the rules. But what do you do when your child (inevitably) breaks the rules? And equally as important, what do you do when they’re actually following the rules?

This is where consequences come in. We’re using the term consequences here to refer to anything, good or bad, that you might do in response to a child’s behavior. Consequences are one of the ways kids learn which behaviors are okay and which are not.

So, how do consequences work? It all comes down to something called behaviorism and, specifically, the theory of Operant Conditioning.

Operant Conditioning

Let’s take a quick trip back to 1930. A young, bespectacled man named B.F. Skinner is a psychology graduate student at Harvard University, and he wants to understand human behavior. He’s sick of all the Freudian psychoanalysts’ nonsense, with their subconscious motivations and their deep-seated desires and their Oedipus complexes. He’s heard about this thing called behaviorism, the idea that behaviors are shaped not by subconscious drives, but by observable factors in the environment, and he is intrigued.

Being the experimental scientist that he is—and presumably, because he’d like to pass his dissertation—he develops something called the “Operant Conditioning Chamber” (or “Skinner Box”). He puts a rat in there6. If the rat presses a lever, it gets a reward (a food pellet). Later, Skinner adds a negative stimulus (i.e., electric shock). Now, if the rat presses a different lever, it gets a very unpleasant burst of electricity to the feet.

The results? Very quickly, rats go full Mario Party on the food-giving lever, mashing the button quickly and frequently, because they’ve learned it will give them a reward. They start to avoid the other lever, because they’ve learned it will lead to something bad.7 Skinner now has proof of his theory of Operant Conditioning, that behaviors are determined by their consequences8, and specifically:

Behaviors that are followed by a good consequence are more likely to happen in the future.

Behaviors that are followed by a bad consequence are less likely to happen in the future.

Skinner is widely believed to be one of the most influential psychologists in recent history and also, kind of a weird guy (see one of his later inventions, a special climate-controlled baby crib that, despite being totally unrelated, does look eerily similar to the Skinner Box).

Though most people now recognize that behaviors are not solely the product of their environmental consequences (thoughts and feelings, for example, also play a role), Operant Conditioning has had a major impact on everything from improving educational outcomes, to developing effective treatments for anxiety, to—you guessed it—parenting.

I feel like I’m in Psych 101. Why are we talking about this, again?

Understanding how Operant Conditioning works can help us use consequences more effectively in our tech parenting, and, of course, our parenting in general.

So let’s dig into the details.

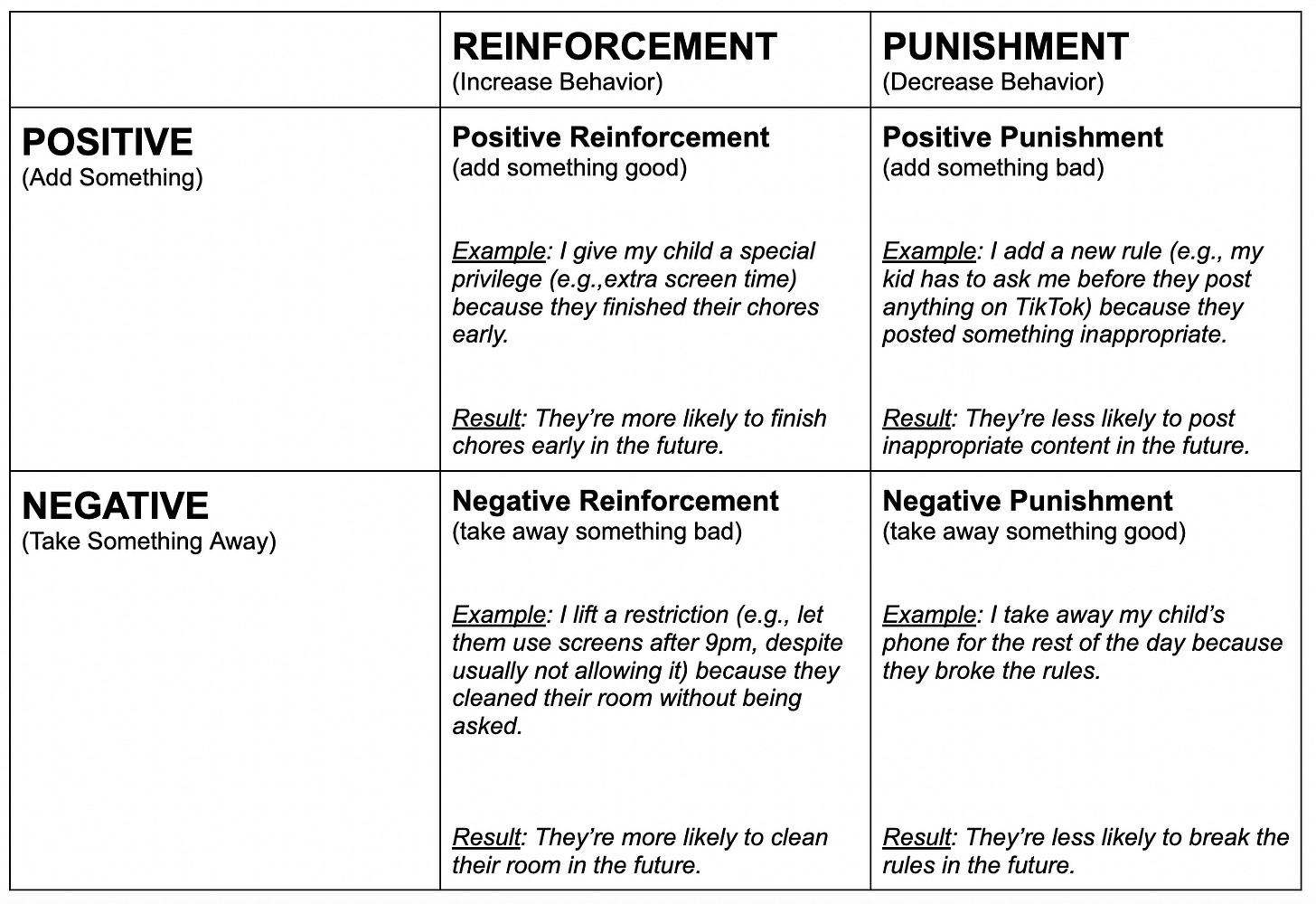

Operant conditioning suggests that there are four separate ways to increase or decrease behavior. The terminology here gets confusing because, you know, psychologists.

Reinforcement is anything that increases the likelihood of a behavior.

Punishment is anything that decreases the likelihood of a behavior.9

Positive means we’re adding something after the behavior. (It does NOT necessarily mean “good”)

Negative means we’re taking something away after the behavior. (It does NOT necessarily mean “bad”)

The best way to understand this is with a quick visual and some (tech-related) examples.

Now, let’s take a moment to discuss how we might apply consequences for a few example behaviors.

I want my 5-year-old to hand over the iPad when screen time is over without a fight.

Effective Consequences:

Positive reinforcement: when my child does put down the iPad, I praise them using specific language that labels the good behavior (I love the way you put the iPad down so quickly and calmly when screen time was over!)

Negative punishment: when my child screams and stomps their feet after the iPad goes away, I ignore it (i.e., withdraw my attention).

Ineffective Consequences:

When my child screams and stomps their feet after the iPad goes away, I engage them in a 20-minute discussion regarding the benefits and drawbacks of screen time for young children.

Why doesn’t this work? Remember: for young kids, your attention counts as positive reinforcement, even (counterintuitively) if that attention comes in the form of scolding or lecturing. This makes a behavior more likely to occur in the future.

When my child screams, stomps their feet, and eventually escalates to rolling around the floor yelling I hate you and you smell like cashews (see above), I give the iPad back.

Why doesn’t this work? In this case, again, giving the iPad back is a positive reinforcer. As hard as it is, if we give in to a child’s escalating behavior, we teach them that this behavior (screaming, yelling insults) results in more iPad time, so they’re more likely to do it in the future. Part of what makes this so hard is that giving the iPad back is actually a negative reinforcer for us, the parents! Something bad (our kid screaming) goes away when we give in, so we’re really tempted to do it again in the future.

I want my 14-year-old to be honest with me when they get into trouble online.

Effective Consequences:

Positive reinforcement: when my child comes to me and tells me about a mistake they made online, I praise them for being honest. (Thanks for telling me about this–I’m proud of you for doing that. I’m really glad we’re having the chance to talk about it).

Negative reinforcement: when my child comes to me and tells me about a mistake they made online, I remove a hypothetical bad outcome. (Because you were honest with me about this, there won’t be any consequences this time).

Negative punishment: when I find out that my child lied about getting in trouble online, I take away something good—for example, I do not allow them to use the social media platform where they got in trouble for a specified period of time.

Ineffective Consequences:

When my child comes to me and tells me about a mistake they made online, I yell at them and take away their phone.

Why doesn’t this work? This response, which involves both positive punishment and negative punishment, makes it less likely that the behavior you want (honesty) will happen in the future. [Note, if you (understandably) accidentally react in a manner that you later regret, you can always apologize and walk it back later.]

When I find out my child lied about getting in trouble online, I yell at them. They yell at me, I yell at them more, and when my child eventually says something totally out-of-bounds, I send them to their room.

Why doesn’t this work? This is a common pattern in families with teens, and the reason it continues is negative reinforcement. Your yelling and screaming is “something bad” for a teen. When they finally escalate to out-of-bounds territory, your yelling goes away. This makes it more likely that their behavior (escalating) happens in the future. The solution here: try, as much as possible, to break this pattern before it starts. If you know you are tempted to yell, leave the situation (or ask your teen to leave the situation), and come back later when both parties are more calm.

Taking a step back

The strange thing about reinforcing (or punishing) behavior is that it often happens outside of conscious awareness. Yes, there are many cases where, say, our child sneaks onto the iPad when they shouldn’t, we don’t allow them any screen time the next day, and they think to themselves, in full, conscious awareness, “Okay, I’m never going to do that again because I don’t like the consequence.” But in many cases, the process is not as obvious. Sometimes we, and our kids, fall into patterns of reinforcing behaviors we didn’t mean to, and vice versa.

Similarly, there are many cases where we think our response to a child’s behavior is entirely neutral. Maybe they do something and we don’t respond at all, for example. But even silence can be a consequence. There’s rarely a “neutral” here. There are also a lot of other, non-parental external reinforcers, like friends, siblings, teachers, and media, that are shaping kids’ behavior, too.

This doesn’t mean that we need to be on constant high alert for inadvertent reinforcement or punishment. But it does mean that, if you’re noticing an unwanted behavior in your house, it may be worth considering what typically comes after the behavior. What are the consequences?

Rethinking discipline

Look to the parenting content on Instagram and TikTok, and you’re left feeling that discipline will somehow destroy your child’s confidence, harm their brain chemistry, and/or give them 20% off with code SUMMERSALE…

But discipline, including the use of consistent consequences with a foundation of warmth and structure, is key to teaching kids how to behave in the world and maintaining a positive relationship with them. We can still validate their emotions. We can support them, and love them, and listen to them. And we can teach them that it’s never (alright, almost never) okay to tell someone they smell like cashews.

Thanks for reading, techno sapiens. We’ll be back later this week with a closer look at one specific consequence: taking kids’ phones away as punishment. Should you do it? When and how? Stay tuned.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

In case you missed it

Interested in Behavioral Parent Training therapy for your own family? Here’s a list of common Parent Training programs, and here’s a reminder on how to find a therapist. And remember, you can always email me (technosapiens@substack.com) with questions.

A big thank you to my friends and fellow former therapists in the BPT clinic, who reminded me of some of these stories via text message. None of us are currently doing this type of therapy, but as we discussed the time one of us sprinted down the hallway after a child and lured them back to the therapy room with a trail of cheerios, we became oddly nostalgic. By the end of the conversation, we were ready to dust off the old princess crowns and get back out there. Ah, memories.

By the way, in researching this post, I came across this excellent Australian website with tons of evidence-based parenting tips and tools for kids of all ages. Also, videos! With Australian accents! These are the best videos I watched this week, with the exception (obviously) of corn kid.

A version of I’ve been working on the railroad with all lyrics replaced by meow’s was simply an annoying sound I happened to think of while writing this post. Surely this doesn’t actually exist? I thought. Techno sapiens: I stand corrected.

But actually—when does one stop cutting up children’s grapes into tiny pieces for fear of them choking? College? That’s reasonable, right?

I’ve never done any research with mice or rats, but I once visited a mouse lab while in graduate school. We took an elevator down to the basement of the psychology building, opened a heavy, locked door, and suddenly, we were surrounded by dozens of cages containing mice in various states of activity—sleeping, scurrying around in circles, doing repeated backflips (seriously—there was a scientific reason for this I no longer remember). It was the stuff of nightmares.

I enjoyed this recent New Yorker article noting that mice are not, in fact, people.

For all of you history-of-psychology sapiens out there: yes, I recognize that we’ve glossed over a lot of the history, here. B.F. Skinner drew heavily on Edward Thorndike’s “Law of Effect” in developing his theory. John Watson is actually considered the “father” of behaviorism, while Skinner is the “father” of operant conditioning. Psychologists, it seems, are the fathers of calling people fathers of things.

It’s important to note that recent meta-analyses have indicated that physical punishments (like spanking or hitting) are ineffective in reducing children’s problematic behavior and may actually have the opposite effect (increasing children’s aggression and rule-breaking).

What does the evidence say about physical punishment (slapping, spanking, etc)?

I'm one of those 90s babies who grew up with it both at school and at home. The product of authoritarian gen X parents and teachers.

I've always thought it was unnecessary and probably harmful. But I have recently heard from some scholars that it can be part of an effective discipline strategy and that people who are totally against it exaggerate the evidence for its harmfulness.

Any clarity on this?

I feel like I’m really struggling with my kids with my preschooler son generally antagonizing and snatching things from his young toddler sister. It’s hard not to give the behavior attention when their interactions constantly devolve into the little one screaming because my son snatched a toy from her and gleefully ran away. Example here but I’m sure anyone with multiple young kids can recognize this type of pattern.