New study on kids and social media

And a little trip across the pond. Cheers!

We’ve got an exciting round of Techno Research this week: summarizing a brand new study led by Amy Orben at the University of Cambridge. Also, check me out on this podcast! A good listen for anyone interested in social media, mental health, and/or soothing NPR vibes.

Summary for Busy Sapiens

Younger teens and girls may experience more negative effects of social media

Girls may be more sensitive to social media at ages 11-13; boys at ages 14-15

Both boys and girls may also be more sensitive at age 19

We need more studies to confirm results

Studies are like people. When a person shares news with you, you need to evaluate the credibility of the source, the plausibility of the information they share, and the number of other people who’ve told you the same thing.

So, when your flat-earther friend (not so credible) tells you that Kim Kardashian is dating Pete Davidson (totally implausible), you don’t believe them. When your avid KUWTK-watching friend (more credible) tells you the same, you start to wonder. And when 15 people, plus The New Yorker, tell you about KimPe, you’re forced to accept that it’s true.

The study we’re talking about today is, of course, just one study, with strengths and limitations. But it is highly credible (i.e., rigorous), and the findings are plausible in the context of prior research. We’ll need more studies before these results are ready to make their red carpet debut, but for now, they’re certainly worth paying attention to.

What’s the study about?

Led by a team at the University of Cambridge, this study involved a massive, nationally-representative sample based entirely in the UK. From a scientific standpoint, this means I’m now required to occasionally use slang I learned on The Great British Bakeoff. Sorry, I don’t make the rules.

The researchers analyzed two existing datasets which, combined, included 84,011 participants (blimey!), spanning the ages of 10 to 80 years old, with yearly repeated assessments between 2011 and 2018.

The goal was to test associations between social media use and well-being (specifically, “life satisfaction”), and to see if these associations differ based on age and sex.

What did the researchers do?

They analyzed two primary variables: life satisfaction and social media use. The exact wording of items varied slightly across datasets and participant ages, but in general:

Life satisfaction was measured with a single item like: Which best describes how you feel about your life as a whole? with answer choices ranging from Completely Happy to Not at all Happy.

Social media use was measured with an item like: How many hours do you spend chatting or interacting with friends through a social web-site or app…on a normal school day? With answer choices including: None, Less than an hour, 1-3 hours, 4-6 hours, 7 or more hours.

Yes, as you might expect, I was absolutely gutted by the choice of a single, self-report measure of time spent using social media. However, in a massive data collection effort like this one, this type of measure is often the best we have.

Also, although self-reports of screen time are not accurate on an absolute basis, new evidence suggests that they actually have good predictive validity. This means that self-reported measures correlate with outcomes like self-esteem and well-being at roughly the same magnitude and direction as actual, objective screen time logs. So maybe, they’re not as bad as we thought. I’m chuffed!

What questions were they trying to answer?

The fact that data was collected every year, and with such a large sample (ranging in age from elderly adults down to wee lads), allows for two types of analyses. This distinction is important, not just for this study, but for science in general2, so it’s worth a quick (oversimplified) discussion.

Between-Person Effects

These analyses look at whether certain people, compared to other people, are more likely to experience a given outcome.

For example, are people who eat bagels happier than those who do not?3 Or, in this case, do people who use more social media report lower well-being than those who use less?

Within-Person Effects

These analyses look at whether a given person is more likely to experience an outcome at a certain time point, compared to their usual.

For example, are people happier than usual on days when they eat bagels, versus days when they do not? Or, in this case, do people report worse well-being, compared to their usual, after periods of higher-than-usual social media use? This is especially useful because, since we’re comparing people to themselves, instead of other people, it reduces the chance that some other difference between people (say, socio-economic status or a certain personality trait) is driving the effects.

So, do teens who use more social media report lower well-being?

In short, it depends on their age.

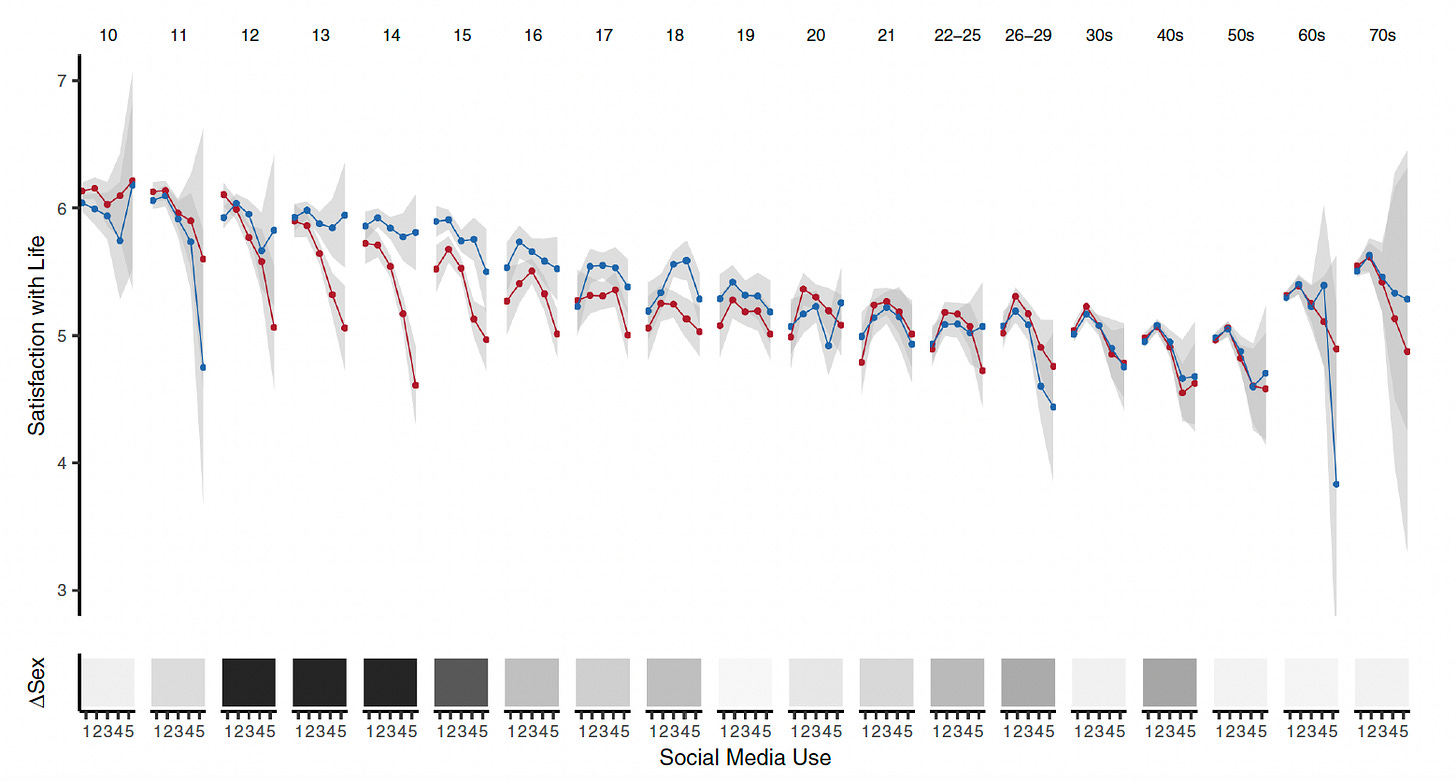

To see how the researchers answered this question, let’s first take a look at this chart.

Say what you will about science being boring or dry, but this, my friends, is a beautiful figure. At the top we have age. On the bottom we have social media use (1=None, 5 = 7 or more hours per day). On the Y-axis, we have life satisfaction. Females are in red, males in blue. The darker shading at the bottom represents ages for which there’s a significant sex difference in the effects of social media on life satisfaction. Bloody brilliant.

So, what we see here is that in younger adolescents, those ages 11 to 15 or so, the relationship is pretty linear. At those ages, kids who use more social media use also report lower life satisfaction. And based on the shading at the bottom of the figure, we know that it’s generally worse for girls.

For older teens and young adults (ages 16-21 or so), we see more of an inverted-U shape. The researchers call this the “Goldilocks” pattern. Too much social media is bad, none is also bad (perhaps due to some kind of social exclusion), but somewhere in the middle might be just right. In this case, that middle is anywhere from less than an hour (option 2) to 1-3 hours (option 3).

For other adults (i.e., those anywhere from 22 to 70s), roughly the same pattern seems to apply, but with a steeper drop-off in life satisfaction after 1-3 hours.

Do teens report lower well-being after periods of higher-than-usual social media use?

In general, yes, but this also depends on age and sex.

This study allows us to do a proper test of this question. By following the same people across many years, we’re able to first establish a person’s baseline, or their typical levels of social media use and life satisfaction. Then, we can look at deviations from that baseline during a given year—that is, years when they used more social media than usual, or years when they reported lower well-being than usual.

The researchers looked at this for young people ages 10-21, over the course of 7 years. They also looked at both directions of effects (i.e., life satisfaction predicting social media use, and social media use predicting life satisfaction).

If people reported lower-than-usual life satisfaction at one year, they used more social media the following year. This was true for all ages. Perhaps there’s something about feeling worse that drives teens to use more social media—a finding that’s come up in other studies, too.

What about the opposite? Did higher-than-usual social media use predict later decreases in life satisfaction?

Here’s where things got interesting. This effect happened only for teens of a certain age and sex. The researchers call these periods—when increases in social media use predicted decreases in well-being—windows of sensitivity to social media.

For girls, this window was between ages 11 and 13.

For boys, the window was between ages 14 and 15.

For both girls and boys, there was another window at age 19.

Remember, this is especially useful because we’re comparing teens to themselves, instead of other teens—so we can be relatively confident that it’s not some other between-person difference that’s driving these effects.

Of course, there could still be other time-varying “third variables” playing a role. For example, perhaps ability to not lose one’s cell phone varies as a function of age. Maybe losing one’s cellphone affects both life satisfaction and time spent using social media, but the social media time doesn’t cause the life satisfaction, per say.

Summing it up

This is just one study. And there are aspects of it that are a little dodgy—crude measures of time spent on social media, small effect sizes, self-reported data. But the study is rigorous, and findings fit within existing evidence for sex and age differences in the effects of social media use. Also, unlike KimPe, the results are relatively plausible. Taking these things together, it’s worth considering the results.

In general, it shows two periods of sensitivity to negative effects of social media—during early adolescence (roughly ages 10-15), and during young adulthood (age 19). It also provides some interesting evidence around sex differences, with negative effects of social media seeming to line up with average pubertal timing (i.e., girls earlier than boys).

What does this mean for me?

I’m not quite ready to say that you should wait until age 15 or 16 to allow your kid on social media. Or that you should stop by your 19-year-old college freshman’s dorm and snatch their phone away while they’re sleeping. I think we’ll need a few more studies to confirm these effects—and also, to dig into exactly why and how social media use might play a role in well-being, so we know what to look out for.

Here's what I do think we can take away from this study:

If possible, consider waiting to introduce social media. Exactly how long to wait? I wish this study could answer that for us, but instead, I think it will depend on the kid—their maturity, their social circle, their emotional health. For context: 13 is the minimum age allowed by most platforms, yet we know that among 8- to 12-year-olds, 38% use some form of social media. There’s certainly no need to rush into allowing social media—and it seems that this may be especially true for girls. Remember, no decisions are final. You could always start by introducing, say, 30 minutes of Snapchat per day, then revisiting. If it’s not working, no more Snapchat for now. If it is working, great!

Be aware of changes in your child’s typical patterns of use. Findings point to changes in usual patterns of social media use as a predictor of future well-being. This speaks to being aware of your child’s typical frequency of social media use, and watching for deviations. If they’re suddenly using social media a lot more than in the past, check in to see whether this new pattern of use is working for them (and you) or not.

If your child is struggling emotionally, pay closer attention to their social media use. Remember, this study also found the opposite direction of effects—lower life satisfaction predicted future increases in social media use. This points to the possibility of a “cascade” effect, i.e., a kid is struggling emotionally, so they start using social media more, then this causes them to struggle more, and so on. If your child is having a hard time emotionally, socially, or behaviorally, you may want to be especially careful about setting limits on social media use.

One thing this study cannot address is why social media seems to have a more negative effect for early teens (vs. older teens), young adults, and girls (vs. boys). But other studies give us some clues—sensitivity to feedback from peers, body image concerns, comparison with others, interference with sleep and other activities. At the end of the day, what may be most important—rather than any one right age to introduce social media—is that we support teens in these concerns.

Full citation: Orben, A., Przybylski, A.K., Blakemore, SJ., Kievit, R.A. (2022). Windows of developmental sensitivity to social media. Nature Communications.

Separating “between-person” and “within-person” effects is actually really crucial to interpreting research findings. Often, we accidentally take between-person findings (e.g., people who eat more bagels tend to be happier than people who eat fewer bagels), and interpret them as within-person effects (i.e., I will become happier if I eat more bagels). Sometimes between- and within-person effects can even go in opposite directions. A classic example of this? Replace “person” with “animal species.” Do smaller animals have longer lifespans? If we look within species, the answer is yes. Smaller dogs, for example, live longer than larger dogs (as evidenced by Lucy, my family’s 16-year-old cockapoo). But between species, smaller animals have shorter lifespans. The bowhead whale, for example, can live up to 200 years, while mice typically live only 3 years.

Yes, I eat a lot of bagels. So many, in fact, that bagels were referenced in my husband’s wedding vows (something along the lines of “For better and for worse, in sickness and in health, in times of bagels and no bagels.” One of the most challenging aspects of attending grad school in North Carolina was the lack of quality bagels (specifically, New York-style everything bagels, toasted with butter). If you live in North Carolina and are now thinking Hey! Our bagels are pretty good! I’m sorry. You’re part of the problem.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

I'm really curious about their use of question for social media use. How much of social media use is scrolling (down twitter, tiktok, etc.) and how much of it is "chatting or interacting with friends". I remembered you breaking down what social media use means, but I can't seem to find it now.