Kid scared of needles? Try YouTube

How video distraction can reduce kids' pain during medical procedures by 10 to 20%

Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

6 min read

Well, yea, we’ll find a vein to insert the needle, and then one of the nurses will hold down his arm. It usually takes a minute or two, so the parent will just need to restrain him during that time.

I’d found out earlier in the week that my 18-month-old son needed a blood draw for some allergy testing. Now, I was on the phone with the phlebotomist (blood draw specialist) at a local clinic. The conversation was not making me feel any better.

Me: So the needle will be in there for a minute two?

Her: Yup.

Me: And I’m supposed to restrain him that whole time. Because he’s not supposed to move at all.

Her: Yup!

Me: And, uh, just confirming, you guys know he’s one-and-a-half, right?

Her: Yes, we have his birthday right here in his chart.

There was a tightening in my chest, and a feeling of unease bubbling up in my stomach. I have not even the slightest concern about needles when it comes to my own veins, but with my son, panic was setting in.

I had flashbacks to a recent visit to the pediatrician. His vaccinations had resulted in heartbreakingly large, fearful eyes staring up at me, a blood-curdling scream, and wild tensing and flailing of limbs, punctuated by the nurse nervously fumbling with the needles and chuckling “wow, he’s a wiggly one.” I recalled learning that the median age of onset of needle phobia is as young as 5, and, by some theories, that early traumatic experiences with needles can confer risk for the condition. I was worried about how this blood draw was going to go.

I needed a plan.

Enter: Ms. Rachel

Songs for Littles is a YouTube channel designed for babies and toddlers. Its more popular videos have amassed over 200 million views. Videos feature the pony-tailed, overall-clad Ms. Rachel, whose hyper-enthusiastic facial expressions (Let’s sing Old McDonald Had a FARM!!!) and multi-syllabic annunciations (O-oh no-o! Whe-ere did the doggie GO-O?!) are equal parts heartwarming and terrifying.

The show is everything you’d imagine from a low-budget educational children’s series: cartoon bunny rabbits, stock footage of children dancing, an adult playing the banjo, singing bananas, etc. And, of course, there’s Ms. Rachel, singing and gesticulating and annunciating with truly impressive precision.

The first time I saw Songs for Littles, the absolutely maniacal enthusiasm emanating from every scene nearly sent me into a state of existential crisis. Is this my life now? I thought, as Ms. Rachel burst into a jaunty rendition of Icky Sticky Bubble Gum.

Then I discovered: my son absolutely loves it.

A few weeks prior, we had turned it on in a fit of desperation while on an airplane, trying to distract him, entertain him, and generally stop him from throwing cheddar bunnies1 at nearby passengers. When we turned it on, it was like a switch was flipped. He was suddenly slackjaw and motionless, his eyes burning holes in my husband’s phone screen watching Ms. Rachel play peekaboo. He couldn’t look away.

And now, I began to wonder: could Songs for Littles serve the same purpose during a medical procedure? Could Ms. Rachel possibly distract him from the pain of the needle insertion?

Surely there isn’t research on this

Why yes, yes there is. Okay, no research on Songs for Littles specifically (that I’m aware of), but there is actually a sizable literature on the use of video distraction for kids during relatively standard, but painful, medical procedures. Commonly studied procedures include venipuncture/phlebotomy (blood draws), intravenous cannulation (IV placement), dental anesthesia, and immunizations or injections (shots).

So, what does the research say? Does watching videos during medical procedures actually make a difference in terms of kids’ pain, fear, and distress?

It turns out, it does.

A comprehensive 2020 meta-analysis published in Pediatrics is titled: Digital Technology Distraction for Acute Pain in Children. It combines the results of 106 studies, including nearly 8,000 children, and finds that the use of technology distractors (like videos, games, and virtual reality)2 reduces pain and distress during common medical procedures, compared to usual care.

Other systematic reviews similarly find positive effects of video and music distraction during vaccine injections (i.e., shots) for both young kids (ages 0 to 3) and children (ages 3 to 12). Interestingly, distraction is actually a better strategy than repeated parental reassurance (i.e., repeatedly saying “it’s okay” or “it’s almost over” during a procedure), which can paradoxically make kids more nervous.3

And how do they do these studies?

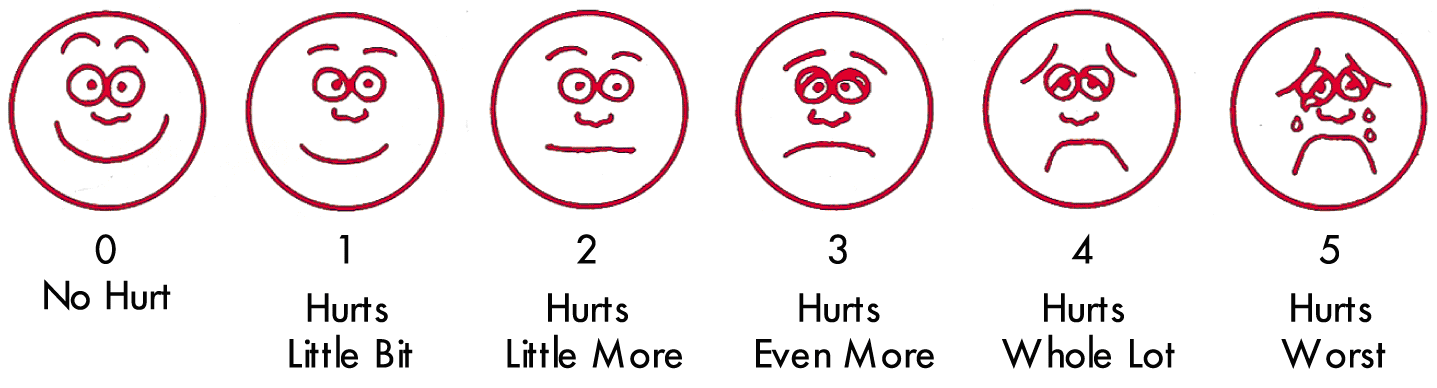

Typically families who present for their routine vaccinations (or other procedures) are randomized to a “digital distraction” or “care as usual” group. Before, during, and after the procedure, ratings of pain and/or distress are taken. For older kids and teens, this might look like a simple Verbal Numerical Scale, i.e., asking them to rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. For slightly younger kids (roughly ages 3-7) you might use a visual pain scale like this:

For kids below age 3, you need a different strategy. If someone were to ask my son to rate his pain on a scale of 0 to 5, for example, he’d likely simply answer with one of his favorite phrases: “no like it” or “bean soup.”4 For these young kids (and sometimes older kids, too) observer ratings are needed. Nurses and parents are asked to rate the child’s distress. In addition, the child’s behaviors might be observationally coded.5

For example, in this 2006 high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) of video distraction during vaccinations in 136 very young children (ages 1-21 months), all procedures were video-taped and a team of undergraduate coders later watched them, using a standard scale to rate the children’s distress (i.e., crying, screaming, flailing) every 5 seconds.6 Children randomly assigned to the “video distraction” condition (i.e., watching Sesame Street or Teletubbies via portable DVD player—this was 2006, remember) showed lower distress than those in the typical care condition before and after the vaccination.

Across studies, the size of these effects are small, but meaningful: the use of digital distraction reduces children’s pain and distress by about 10% to 20% on commonly used scales.

To me, this seems like enough to give it a try.

The Bottom Line

Across studies, distraction is a particularly effective coping strategy for children during painful medical procedures. It’s not clear from the research whether the use of digital distractions is better than, say, distraction with a toy or a parent’s singing voice, but as the authors of that 2020 meta-analysis argue, screen-based distractions offer some “unique advantages.” They require no training to implement, for example, they limit infection control issues, and they’re easily accessible via the smartphones in nearly every parent’s pocket.

So why don’t we use them more during our children’s medical procedures? Doctors’ and nurses’ limited time, maybe? A simple lack of knowledge, or belief that it’s “just a shot”? Or, I worry, our own fear of judgment for bringing “screen time” to the doctor’s office?

On the day of my son’s blood draw, we came prepared with Songs for Littles downloaded on my husband’s phone and the volume turned up. It could not have gone more smoothly. Ms. Rachel’s voice rang out across the phlebotomy room (Tha-at was so-o FU-UN!!!), and my son’s eyes stayed glued to the screen, even as he cried briefly during the needle insertion. A child life specialist sat nearby with some kind of lackluster spinning, light-up toy, in which my son had no interest. It had nothing on that phone screen.

By the time the nurse placed a bandaid on his forearm, he was calmly watching a cartoon rendition of Old McDonald, a tiny smile forming on his face.

Ms. Rachel, if you’re out there, thank you.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

In case you missed it

True or false: Annie’s Organic Cheddar Bunnies are actually just Goldfish rebranded for millennial parents?

This meta-analysis covers the full range of technologies that might be used as distractors: watching movies or TV, virtual reality, playing video games, playing games on a tablet, and even, in the case of 4 studies, a “humanoid robot.” I don’t know about you, but “humanoid robot” is not the first thing that comes to mind for me when I think about reducing fear.

Obviously, we’ve only talked here about the use of technology-based distractions during children’s medical procedures. There are other evidence-based strategies for reducing pain and distress, too, like making a coping plan, applying numbing cream in advance, and having the doctor or nurse administer the most painful vaccine last. Highly recommend this post by Melinda Wenner Moyer and this one from the American Academy of Pediatrics for more info. Also, if your child has a severe needle phobia, you might consider exposure therapy—tips on finding a therapist here.

Kid loves bean soup. Like, a scary amount. If Ms. Rachel ever makes a video about bean soup, we are in deep, deep trouble.

It’s worth noting that many of these studies do not meet strict quality standards for RCTs for a few reasons. First, it’s very hard, if not impossible, to mask the condition to which subjects have been assigned. In other words, people (obviously) know whether a kid is watching a video or not. This could bias ratings of pain and/or distress. If I’m a parent and I believe having my child watch Ms. Rachel will lessen his distress, I might be more likely to rate his distress as lower when assigned to the video-watching condition. Second, these trials often take place in “real world” settings (e.g., in an actual pediatrician’s office), which makes it hard to control all possible confounding variables. Third, pain ratings are notoriously challenging. On the one hand, pain is subjective, so self reports are valuable. On the other, kids are not great at self-reporting nebulous concepts like “pain.” Observational coding is challenging, too. Kids display pain in different ways—some very obviously (screaming, crying), some less so. It removes the bias of self-reporting, but can introduce other biases instead.

A quick note to congratulate the authors of the infant DVD-watching study: their team of undergraduate coders reached 98% agreement. These people were coding the behavior of an infant every 5 seconds over the course of a video clip that likely lasted 5 to 7 minutes, and they agreed with each other on what they saw 98% of the time! Do you know how crazy that is? I can’t think of a single person in my life with whom I agree on anything 98% of the time. Also, the authors specify that each coder watched 35 videos. That’s roughly 200 hours of video of screaming babies getting shots. This is my nightmare.

False. Cheddar Bunnies are rebranded Cheez-Its for millennials 🫠

What about devices like the shot blocker?