New study: A better way to kill time

Petition to replace our phones with Giant Jenga

Hi! I’m Jacqueline Nesi, a clinical psychologist, professor at Brown University, and mom of two young kids. Here at Techno Sapiens, I share the latest research on psychology, technology, and parenting, plus practical tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

6 min read

Think about the last time you were in a waiting area: the doctor’s office, the line at your local coffee shop, the hallway outside your child’s preschool classroom. How did you spend your time?

Did you stand, looking around, quietly glancing at the children’s handprint artwork or the educational poster about spotted lanternflies?1 Did you keep your eyes fixed on the floor tiles, trying desperately to avoid eye contact with that guy who always comments on your coffee order (why is he always here?)?2 Or did you, in a temporary fit of madness, actually strike up a conversation with the person next to you?

Chances are, the answer is none of the above. If you’re like most people—myself included—you spent the time staring at your phone.

Oh, yup, that sounds familiar

The vast majority of U.S. adults report using their phones when out in public—73% say they have done so just to give them “something to do” and 54% to “avoid interacting with others” near them. And nearly 90% say they’ve used their phone at their most recent social gathering.3

So, why do we do this? And what impact does it have on us?

Let’s find out.

Science! Hooray!

In a fascinating new study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,4 researchers at the University of British Columbia set out to test why, exactly, people turn to their smartphones during social interactions, and how doing so affects them.

Here’s what they did:

The researchers recruited 395 college students.

They created a fake “recreation room” that served as the setting for the experiment (complete with a Giant Jenga game!).56 Students spent 20 minutes waiting in the recreation room in groups of three or four.

Half of the groups were randomly assigned to wait without their phones, and half to wait with their phones.

The researchers went to great lengths to ensure students were unaware of the purpose of the experiment, telling them it was a study of “how biological markers, such as cortisol, change over time in everyday life.” They even collected saliva samples before and after the 20-minute waiting period (which they promptly threw away), to increase the plausibility of the cover story.7

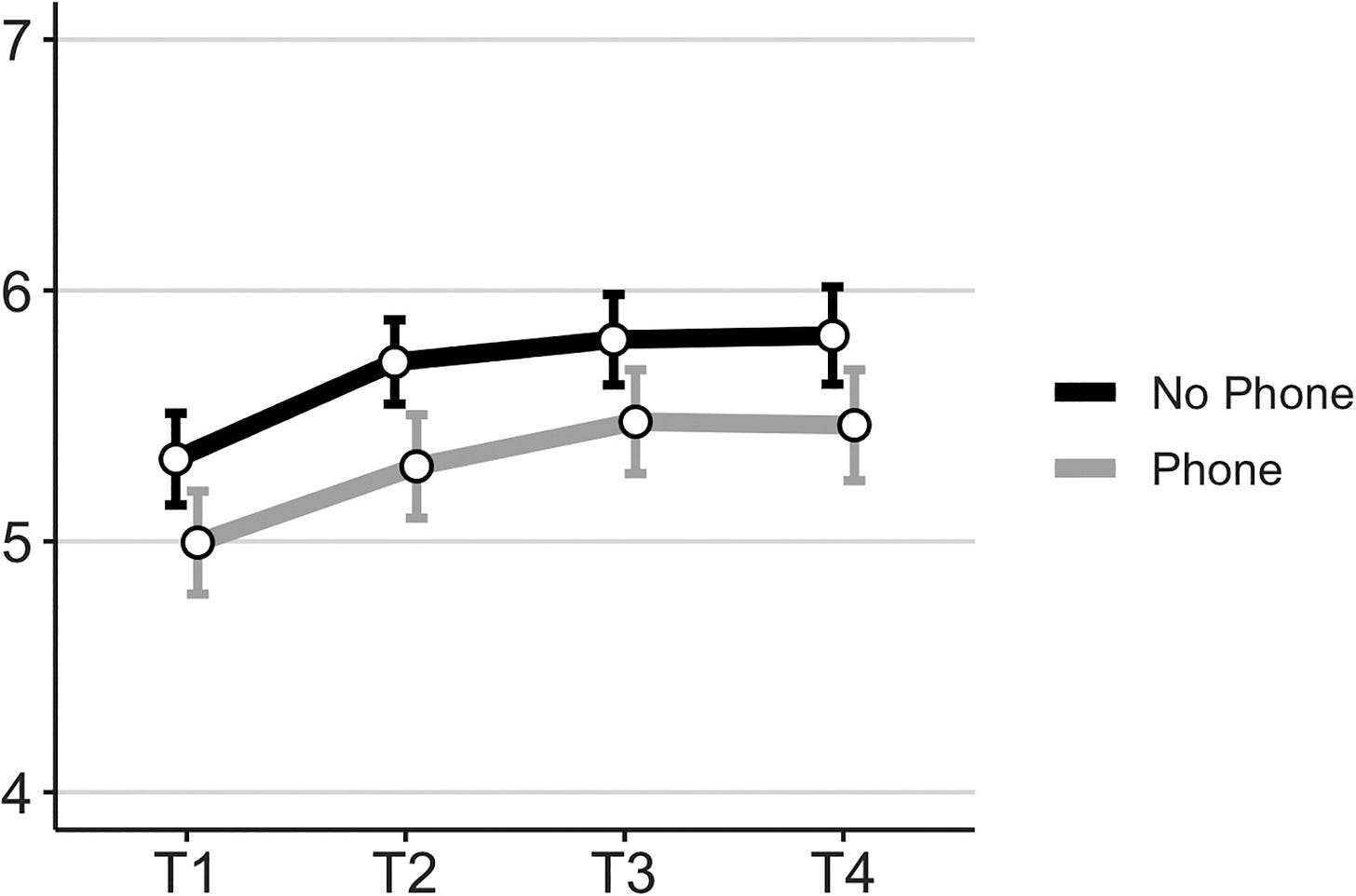

A video camera recorded students’ behavior while in the waiting room. Students also filled out questionnaires after the waiting period. These questionnaires assessed how much they had enjoyed the first 5 minutes of the waiting period, as well as minutes 6-10, 11-15, and 16-20.

What did the researchers expect to find?

The researchers went into this study with an assumption that many of us likely share—that using our phones during a social interaction provides us with some small benefit. Maybe it eases the awkwardness of those first few minutes with strangers, and makes us feel more comfortable, less bored, and—at least temporarily—a bit happier.

Because of this, they expected that participants in the “with phone” condition would report temporary increases in enjoyment during the first 5 minutes of the waiting period. Over time, they thought these increases would go away, and students in the “without phone” condition would be the happier ones during minutes 6-20.

And is that what they found?

Yes and no.

In sum: As expected, participants without phones enjoyed the waiting period more than those with phones. But contrary to what the researchers expected, there was no temporary benefit of phone use during the first five minutes—the group who had access to their phones just felt worse the whole time.

In detail: Compared to participants in the “with phone” group, those who didn’t have their phones reported that they socialized more with others in the waiting room. When the researchers watched the video recordings, this was confirmed—in the phone group, 27% of participants didn’t socialize at all, but this number was only 6% in the no phone group.

Plus, the effect of phone use on enjoyment was mediated by time spent socializing, which is just a fancy, statistical way of saying that socializing less was probably the main reason why the phone-users felt worse.8

So, should we trade our phones for Giant Jenga?

Here’s why this study matters:

When we think about the effects of phone use, we often consider the alternative. That is, if the alternative to using our phones is just sitting there, awkwardly waiting in a room with some strangers, are we really missing out on anything by using our phones?

But what if we’re bad at predicting what will actually make us feel better? This study suggests that, maybe, we’ve been assuming wrong all along. Even the researchers assumed that a little phone use would make people feel better in the short-term. Instead, those who left their phones behind fared better from beginning to end. They talked to the strangers around them. They felt more connected. And ultimately, they were happier.

So, how can we apply this finding in our day-to-day lives?

Everyone: Consider putting your phone away during “waiting” times, especially when there are other phone-free people around you. It might feel awkward or boring at first, but chances are, phone use won’t actually make us feel much better in the moment.

Parents: Try implementing “phone free” times (e.g., dinner, before school) or locations (e.g., the car, the living room) to spark more conversation.

Schools: There are many factors that influence schools’ decisions around student phone use during the school day, but this study is one point in favor of “phone-free” environments (even during more unstructured times, like in the hallway or lunchroom).

Everyone: Consider setting “phone-free” times with family or groups of friends, especially when meeting new or less familiar people.

Postscript: Science in action

I wrote this post in a coffee shop, surrounded by strangers. At one point, I was so engrossed in my computer screen that I barely noticed a man approaching my table, until he bent down to make eye contact and said something like, Hey, do you have a second?

My first thought, of course, was Oh God, no.

But what if I was assuming all wrong? What if looking away from my devices and engaging with this stranger would actually make me happier in the long run?

Sure, I said.

You were looking so serious, working so hard at your laptop, he said, and then, holding up a post-it note, you seem like someone who would be interested in this.

Things got weirder from there. He told me he’d been listening to the audio version of a book called The Game of Life and How to Play It and that he’d been struck by a quote, which he’d written on the post-it and wanted to share with me: Your thoughts are like magnets, they attract experiences and people that are in alignment with them. Somehow, this conversation also spanned the fact that he was a chiropractor, a former Catholic, married (so, not to worry, he wasn’t hitting on me), and that he keeps a list of inspirational quotes (his own quotes, that is) in the Notes section of his phone. Oh, also a brief mention of the song Let it Be.

Twenty minutes later, I returned to my computer screen. That wasn’t so bad, I thought. Then I got to work writing about it, smiling a little bit to myself as I did.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

Does anyone else live in an area of the U.S. with full-blown Spotted Lanternfly panic? This invasive species can now be found in 14 states, and one method to control the spread, apparently, is to have regular citizens simply kill them when they encounter them. More specifically, the posters dotting my town state that, should you see a spotted lanternfly, you should “eliminate” it, which kind of makes me feel like a villain in a Marvel movie?

Is a large iced coffee with chocolate syrup and milk really that strange of an order?

Teens may be so convinced that using their phones is better than standing idly that one study finds nearly half (45%) of teens have pretended to text while in public. And if you’re an adult who’s never pretended to text...I don’t believe you.

Full citation: Dwyer, Zhuo, & Dunn (2023). Why do people turn to smartphones during social interactions? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Alright, let’s talk about the Giant Jenga thing. Here’s the justification the researchers provided: “In order to make the laboratory feel more like a rec room, and to provide an activity for groups to do, the tower-building game Giant Jenga was provided in the corner of the room.” I immediately became obsessed with this detail of the study. Surprisingly, the researchers report “participants in the phone and phoneless groups did not report significantly different amounts of time playing Jenga,” so lack of phones did not, in the end, increase Jenga-playing time. A detail that is missing from the study, though, is the actual amount of time each group spent playing Jenga. Was it a few minutes? The full 20 minutes? Zero minutes? I must know.

Okay, I know this wasn’t the point of the study, but I cannot stop thinking about that Giant Jenga game. Imagine you’re just a regular, old college student studying psychology, and you show up to fulfill your course credits. Then you have to sit in a room for 20 minutes with some strangers, and they’re like “Hey! We know you don’t really want to be here, but how about this GIANT JENGA to make it better? Play it if you want! By the way, we’re filming you.” Makes my palms sweat just thinking about it.

I must say, collecting fake saliva samples is an astonishing level of commitment to the cover story here. This involved having participants suck on a cotton swab and then place it in a plastic bag, both at the beginning and end of the waiting period, only to throw them all away immediately afterward. Talk about dedication to the science!

Some interesting, additional findings of the study: People who were more introverted were more likely to use their phones during the waiting period. Also, among all people who used their phones during the study, 59% began doing so during the first minute, and the behavior seemed to be contagious, such that when one person began using their phone, others did, too. According to the researchers: “…if anyone feels uncomfortable in a social situation, they may turn to their phones, leading others around them to mimic their behavior in a way that perpetuates negative outcomes for the group.”

We always know that we're going to a waiting room. What we don't know is whether we're going to be waiting very long in that room. I always bring something to a waiting room to do whether it's emails to answer on my phone or notes and cards to write to catch up with people, knitting, crocheting, a book that I'd like to finish. Sometimes I bring knitting or crocheting and the book and do both. Why is this not an obvious choice? I'm fully aware that I'm not always going to be " the first one" in the line!! I'm always happier when I have accomplished something

Thanks for this awesome article! This study is so interesting.

About the lantern flies...we've had them for years here in PA. 😕 thankfully this season they've been sparse at least where we are. Embrace the villain role - they are invasive and need. To. Go.

One time I saw a woman in the park scraping HANDFULS of lantern flies off a tree into a bag so she could get rid of them. Doing her civic duty 🫡

I recommend coming at them quietly from the front so when they jump they land right into the trajectory of your stomping foot 🦶

Happy stomping!