Parents' ultimate guide to video games

Part 1: The basics, how frequently kids are gaming, and how much is too much

Know someone who might be interested in Techno Sapiens? Support the newsletter by sharing this with them!

Summary for busy sapiens

79% of families report having a video game console at home.

8- to 18-year-old boys spend 2 hours, 20 minutes gaming per day on average; girls spend 54 minutes.

There’s little evidence of harm associated with gaming, and some evidence of social and cognitive benefits.

But for ~1 to 9% of teens, video gaming can become problematic and interfere with daily functioning.

11 min read

I have a few distinct memories of playing video games growing up, and most of them involve Mario1.

I’m sitting next to my older brother on the carpeted floor in our basement, our faces mere inches from the TV. In our hands, we’re clutching rounded, gray Super Nintendo controllers. We’re carefully timing our presses of the purple “A” button to ensure Mario jumps on top of the nearest green pipe.

A few years later, I’m squeezed between two brothers—one older, one younger—in the middle seat of the family car. We’re peering at the pixelated screen of a Game Boy, its familiar beeping refrains echoing as Mario jumps on a mushroom.

Years after that, I’m sitting on another carpet, in a new house, in another part of the country. Now, I’m surrounded by my two brothers and a younger sister2, each of us screaming at our on-screen Mario Kart character to go faster. Our thumbs are turning white with pressure against the tiny joysticks on our Nintendo Cube controllers. I groan as Toad races straight off the side of Rainbow Road.

A few weeks ago, Universal released the much-anticipated trailer for the forthcoming Super Mario Bros Movie. Chris Pratt voices Mario, and in the months leading up to its release, seems to have gone full Daniel Day-Lewis3 on the role. In interviews, he noted that he’d been working closely with the directors to flesh out the voice, had “landed on something that [he’s] really proud of,” and that “[the voice] is updated and unlike anything you've heard in the Mario world before.” Now the trailer is out, and it kind of just sounds like Chris Pratt, except maybe vaguely from Brooklyn? Needless to say, the Internet has lost its mind4.

Long gone, it seems, are the days when we’d sit on our carpets, eyeballs glowing with TV static, listening to shouts of Mamma mia! And Its a-me, Mario!

Video games have gotten a little bit more complicated.

So, techno sapiens, we’ve got a two-parter on video games. Today, we’ll cover the basics, how frequently kids are gaming, and the research on how much is too much. Next week, we’ll be back to talk about the content of games, including a deep dive on violent video games.

[Mario voice] Let’s-a go!

What are video games?

As you might have guessed based on my previous references to gaming consoles that have been out of use for nearly two decades, I am not currently a person who plays video games. However, many people, including at least 43% of U.S. adults, are.

If that 43% includes you, you may want to skip this section. For the rest of us, we’re going to start with the basics.

There are three primary ways to play video games: on a computer, on a smartphone (or tablet), or on a TV.

On a computer (Mac or PC), you typically buy the game, download it, and play it using a service like Steam.

On a smartphone or tablet, you would download gaming apps through the App Store or Google Play.

On a TV, you would connect a console, i.e., the machine that you plug into the TV (or, what comes to mind when my fellow noobs5 and I think of “video games.”) The most popular consoles are Sony Playstation, Microsoft XBox, and Nintendo Switch. Different games are available for each, and all have options for online multiplayer gaming—often involving voice and/or text chat between players who are in different locations (e.g., your son and his friends at their respective houses).

There are a number of different types of video games, and hundreds of thousands of games6, currently available. Here are some that may sound familiar to you:

Sandbox games. These games tend to be nonlinear, open-ended, and creative. Minecraft, the current most popular game7 in the world, is an example.

Shooter games. These can be “first-person shooter” (FPS) or “third-person shooter” (TPS) depending on the point of view of the player. Many games allow players to toggle between first and third person. Example: Call of Duty.

Battle Royale games. The goal of these games is typically to be the “last man standing,” by finding equipment and weapons, and eliminating opponents. Examples: PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), Fortnite Battle Royale.

Sport games. Some of these involve players and teams from professional leagues (FIFA, Madden NFL, NBA 2K). Others involve slightly less realistic play, i.e., Mario Kart.

Role-playing games. In these games, the player takes on the role of a character who develops and gains new abilities through the course of the game. Subgenre: Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMPORG), where hundreds of players are interacting online simultaneously. Example: World of Warcraft, The Witcher 3

Puzzle games. Typically involve logic, pattern recognition, or word completion. Examples: Tetris (still one of the most popular games available!), Candy Crush Saga.

Many games involve elements of multiple genres. Best-selling Grand Theft Auto, for example, is a sandbox game with shooter game elements.

For an extremely detailed list of video game genres and subgenres, this Wikipedia page is your best bet.

Video games by the numbers

Let’s start with the statistics. We’ll be drawing on a few different nationally-representative samples to present data on younger kids (ages 11 and under), tweens (ages 8-12) and teens (ages 13-17).

How many kids play video games?

Most of them.

79% of families with kids ages 8-18 report having a video game console at home

Younger kids: 51% of parents of younger kids report that their child uses a gaming console or portable game device.

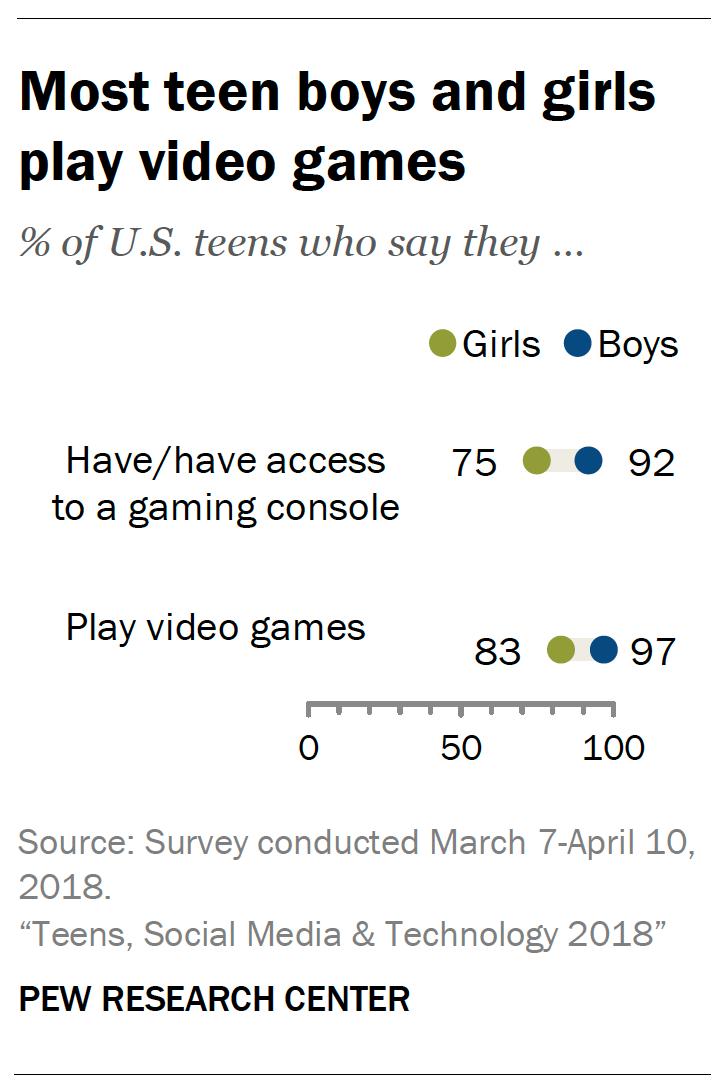

Teens: Video games are nearly universal. 97% of teen boys, and 83% of teen girls report playing video games of some kind (computer, console, or mobile)

How much do they play?

A lot.

Tweens: 43% play video games on a mobile device everyday; 23% play on a console or computer everyday. The average daily time spent gaming is 1 hour, 27 minutes.

Teens: 40% play video games on a mobile device everyday; 26% play on a console or computer everyday. The average daily time spent gaming is 1 hour, 46 minutes.

Tweens and teens: Boys spend more time gaming than girls. Boys ages 8-18 spend an average of 2 hours, 20 minutes per day gaming across devices (!), compared to 54 minutes for girls.

How do parents feel about it?

They have mixed feelings.

Younger kids (11 and under): 51% of parents of younger gamers report that their child spends too much time playing.

Teens: 86% of parents of teens report that teens spend too much time playing video games; but 71% also believe that video games can be good for teens

How do kids feel about it?

They have mixed feelings, too.

Tweens: 47% of tweens report they enjoy playing video games “a lot.”

Teens: 39% of teens also report they enjoy playing video games “a lot.” At the same time, 41% of teen boys (and 11% of teen girls) say they spend too much time playing video games.

How much is too much?

For those in the throes of parenting tween or teen boys, these numbers may not be surprising. For those of us still blessedly ignorant of Creepers and ItemStacks, they may come as a bit of a shock.

So, how much time playing video games is too much? When should we be worried?

In order to answer these questions, we first need to understand whether there is anything inherently harmful about playing video games. Let’s put aside the content of games (i.e., violent versus not) for now—we’ll come back to that next week. The question for today is this: in general, does playing video games negatively impact kids’ mental health?

The answer, across hundreds of studies and more than two decades of research, seems to be no.

A highly-cited 2015 meta-analysis of 101 studies finds that in general, kids who play more video games show slightly higher levels of ADHD symptoms, depressive symptoms, and aggressive behavior. However, after controlling for other variables (like gender, prior levels of aggression, and family environment), these effects essentially disappear. In other words, seeming negative effects of video games probably just reflect differences between the types of kids who play more video games versus less.

Even more interesting, recent evidence, like this large-scale fMRI study published last week—and, perhaps more consequentially, tweeted by famous psychologist Adam Grant—suggests that playing video games may have cognitive benefits for kids, including improved working memory and response inhibition.

As with all studies, this one has limitations–we can’t determine directionality (i.e., are kids with better working memory simply choosing to play more video games?), and there are, in my mind, questions of generalizability (fMRI tasks are often video game-like, so perhaps it’s no surprise that gamers perform better at them). However, prior work, including this rigorous 2018 meta-analysis, also supports the potential benefits of certain video games for improving cognitive skills like perception (i.e., detecting objects), spatial cognition (i.e., imaging objects in 3-dimensional space), and attention.

Video games may also provide an important social outlet for tweens and teens, especially boys. During the pandemic, 70% of 8- to 18-year-olds reported playing video games online with friends, with a full one-third (32%) of boys playing online games with friends everyday. And prior to the pandemic, video games were already a key factor in boys’ social lives—in a 2015 national survey, 91% of boys reported playing video games with friends in-person, and 92% reported ever playing online with friends, with 68% doing so weekly or more.

So, in general, time playing video games does not appear to have significant negative effects, and it may actually have some benefits. But this doesn’t tell the whole story.

When it comes to time spent playing video games, there are two other factors we need to consider.

1. What are video games replacing?

Although video gaming itself is not problematic, there should be some consideration of what activities it is replacing. When the choice is between gaming online with friends versus watching TV alone, gaming might be the better option. When the choice is between gaming and sleep, that’s a little different.

A 2015 meta-analysis including studies of over 85,000 adolescent participants found small associations between video game use and later bedtimes—the suggestion, of course, being that video games can get in the way of sleep. Similarly, a 2019 meta-analysis published in JAMA Pediatrics finds associations between more time spent gaming and lower academic performance. Though many of the studies highlighted suffer from the same limitations noted above, they provide some evidence that video games can displace time spent on sleep and homework.

This is fairly logical: 3 hours spent gaming is 3 hours spent not doing other things. This is not necessarily a problem—video games can be a perfectly fine (and potentially beneficial) downtime activity. But it does suggest that we should be considering the full picture of how our children are spending their time, and whether there’s enough time left in the day after gaming to accomplish things we know are important for health, like sleep, academics, physical activity, and in-person socializing.

2. When does gaming become an “addiction”?

To this point, we’ve been discussing typical video game play, which, for many kids and teens, can still add up to a significant amount of time. But it’s important to note that there is such a thing as truly problematic or pathological gaming (i.e., Gaming Disorder), often colloquially called video game “addiction.”8

Researchers have debated what it means to have an “addiction” to video games, but there is general consensus that certain patterns of use indicate a problem, particularly when they cause significant distress or impairment in daily life.

Here’s what to look out for:

Impaired control over gaming, meaning the person is unable to control how often they play or when they stop.

Increasing priority given to gaming over other interests and activities. In other words, the person may begin to feel that gaming is more important than anything else, and may stop engaging in other activities like seeing friends, participating in extracurriculars, or even going to school.

Continuing (or escalating) gaming despite negative consequences.

How many people meet this description is not clear, but rigorous studies of adults (like this one and this one) suggest the prevalence is somewhere between 0.3 and 3% of the population. Among teens, prevalence estimates range from roughly 1 to 9%.

If you are concerned about your child’s gaming behavior, it’s important to reach out to your pediatrician or a mental health professional. Treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can help.

Summing Up

Video games have come a long way since the days of Super Nintendo, and as the technology has grown more complex, so too have questions around whether, when, and how much to allow our kids to play them.

Playing video games—even for as much as an hour or two per day—may be commonplace among children and teens, and the research suggests that there’s no inherent harm in this. Playing video games, in general, does not seem to be associated with negative mental health, and, in fact, it may some social and cognitive benefits. At the same time, it’s important to pay attention to what video games are replacing. If they’re getting in the way of other valued activities, like sleep or homework, it may be time to cut down. Finally, for a very small share of adolescents, video game use can become problematic and highly impairing—in those cases, it’s important to get professional help.

And that’s all we have for Part 1! We’ll be back next week for Part 2, where we’ll talk about the content of games, including how to think about violent video games.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

My other video game memories mostly involve Oregon Trail, and specifically, the agony of losing all your belongings after a momentary hubris inspires you to “ford the river.”

You’ll notice progressively more siblings appearing in each of these video game memories; I am the second-oldest in a family of 6 kids.

Apparently, when method actor extraordinaire Daniel Day-Lewis was playing Abraham Lincoln in the movie Lincoln, he forced the cast, crew, and director Steven Spielberg to call him “Mr. President” for the entire length of production.

I cannot stop laughing at the Internet’s reaction to Chris Pratt’s highly anticipated Mario voice. A few headlines: We were promised a voice ‘unlike anything you’ve heard in the Mario world before’. In The Super Mario Bros film, we got Pratt doing Paulie Walnuts instead [The Guardian]; Chris Pratt’s Mario Voice Baffles Fans After First Listen: ‘Holy S— It’s Literally Just Chris Pratt’s Voice’ [Variety]; and my personal favorite, Chris Pratt’s Mario voice has a vaguely Italian thing going on in the first trailer [Polygon].

For those wondering: yes, noob is a word. Merriam-Webster defines a noob as “a person who has recently started a particular activity.” Apparently, since it comes from the word “newbies,” an alternate spelling is “newb” (fancy!). According to wiktionary, derived terms include: noob cannon (a weapon used by beginners in shooter games), nooblet (seems to just mean the same thing as noob?), and noob tube (an overpowered firearm in shooter games).

Note that I am not necessarily recommending the games listed here, only naming them because they are currently popular. For recommendations for kids, check out Common Sense Media’s Game Reviews. They note that Grand Theft Auto, for example, “brims with gang violence, nudity, extremely coarse language, and drug and alcohol abuse,” and that “Few games are more clearly targeted to an adult audience.” And of Mario Kart 8 Deluxe, on the other hand, “There's some violence with fireballs, shells, and other animated weapons, but it's cartoonish in nature and there's nothing graphic shown.”

Minecraft is currently the most popular game based on copies sold. Across all platform, it’s sold 238 million copies. The most popular game based on registered users is PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds (PUBG), with 1.2 billion players worldwide.

For those who really want to get in the weeds, here’s a brief rundown of the diagnostic status of video game “addiction.” As of 2019, a mental illness called Gaming Disorder, characterized by problematic gaming that interferes with daily functioning, is included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the global diagnostic tool maintained by the World Health Organization. In a bit of a metric system versus imperial system situation, the U.S. uses a different diagnostic tool than the rest of the world. It is called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM), and in it, “Internet Gaming Disorder” is not formally included, except as a “condition for future research.” Among other arguments, the Gaming Disorder detractors say that symptoms of video game addiction are more likely to be a result of an existing disorder–like depression or ADHD–rather than their own disorder. It remains to be seen whether Gaming Disorder will be officially included in the next version of the DSM.

Thank you. Can’t wait to read part 2. We must be a similar age because I have similar video game memories as you.. curse the Oregon trail !

My kids don’t play video games as much as they watch other people play video games. There is a whole genre of you tube dedicated to “play throughs” and my kids love them. Do you know of any research about harm/benefit of this past time. Also, separate question. How does virtual reality gaming play onto this or is it still too soon in the game to know?