Should I post or should I scroll?

So come on and let me know.

If you haven’t already, please consider subscribing to Techno Sapiens. You’ll get posts delivered straight to your inbox and join a growing community of amazing humans.

4 min read

We’re back with another round of Techno Research, where I try to summarize a recently published scientific study in the least boring way possible. This week: a study led by Patti Valkenburg at the University of Amsterdam.1

Take a second to think about everything you do on social media: scrolling, commenting, liking, posting, re-sharing, reading messages, sending messages, etc.

Now, when you want to do research on which social media activities might be better or worse for a person’s well-being, you need to figure out how to categorize these activities. You can’t conduct a study in which you ask about every single activity a person might do (e.g., How often do you post something complaining about Delta airlines? How often do you watch videos of cats re-enacting the Lion King scene where Scar kills Mufasa? How often do you “like” photos of Half Baked Harvest’s 5-Minute Chocolate Chunk Banana Bread Mug Cake?) It’s impractical, non-comprehensive, and useless for drawing general conclusions.

So, if you had to put all these activities into just two categories, how would you do it? You could separate them into public (e.g., posting a video) versus private (e.g., messaging a friend). Or maybe photo-based (e.g., looking at photos) versus text-based (e.g., reading a Tweet). Or social (e.g., messaging a friend) versus non-social (e.g., checking a recipe).

Most commonly, researchers have categorized social media activities as active versus passive. Active social media use includes activities like posting and sending messaging. Passive use involves simply scrolling, browsing, or watching. Most of us devote a majority of our social media time to passive use.

In the past, scientists generally argued that passive use was harmful to our well-being, whereas active use was fine, or even good. This makes intuitive sense. If we’re just sitting there, staring blankly ahead as TikTok pours a garbage pile of content directly into our eyeballs, this might be bad for us. But if we’re sitting, editing a photo, thinking of a clever caption, reflecting on the meaning of, say, the man in suit levitating emoji2, this might involve some solid brain power. It also might lead to us getting some positive feedback and support, which could make us feel good.

But this week’s study3 refutes that claim. The researchers found that, in fact, the majority of studies do not cleanly support this “passive is bad, active is good” hypothesis.

Let’s dig into the details.

What the researchers did

They searched for every study that was published on active and passive social media use between 2017 and 20214 (other reviews had already been done on studies published before that). This turned out to be 45 studies, 40 of which were “survey-based” (i.e., they measured social media use by asking survey questions about it, rather than by doing an experiment).

They combed through each of those studies to identify, among other things: (1) how the study defined active and passive social media use, and (2) whether active and/or passive social media use was associated with well-being (happiness, life satisfaction, positive emotions) and/or ill-being (depression and negative emotions).

What they found

Across the studies, there were 29 (!) different versions of scales to measure active and passive social media use. In other words, this is really hard to define and measure.

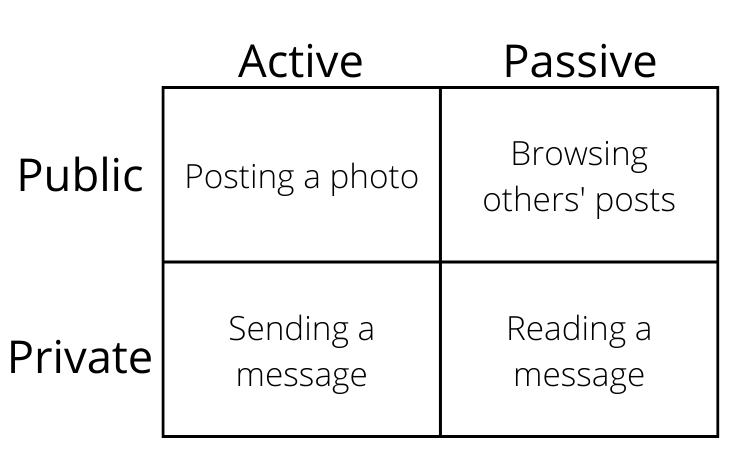

One of the key complicating factors across these studies was the idea of “private” versus “public” social media use. Here’s a 2x2 chart showing an example of each type of use.

When they were measuring the effects of active versus passive social media use, a pretty large number (28%) of the studies treated public use as it were the same as private use. This is a problem because other studies show that the effects of active versus passive use depend on whether they were done publicly.

In the end, few studies actually supported the idea that active use is good and passive use is bad. In fact, over 70% of studies refuted this idea.

Why this matters

We really want to be able to say that one type of social media use is good, and one type is bad—if it were that simple, we could just stop, say, browsing other people’s photos, and we’d all be happy as tech-savvy clams. Unfortunately, it’s not that easy.

This study reminds us that the ways we use social media are complex. It’s actually really hard to distinguish different “types” of social media use. Think back to the time you spend on social media. Maybe you open up Instagram, you post something on your story, then you scroll for a few minutes, liking and commenting on a couple posts along the way. Then you pop over to your messages and send a quick few, then you scan through a few other people’s stories, you check in on your own story’s views, and so on. Was this active? Passive? Public? Private? As in all cases, it was likely some combination.

Instead of relying on this rudimentary distinction, then, the authors argue for taking other factors into account, including:

The types of content people view, post, send, or receive

The people (i.e., you and your friends/followers) who are doing that viewing, posting, sending, and receiving

So, what does this mean for me?

It may matter less whether you’re using social media actively or passively, and more whether you’re doing each of those activities in a way that works for you, personally. Here’s how to take these factors into account in your own, or your children’s, social media use.

The What. Consider what kinds of content you are viewing, posting, sending, and receiving. Are they positive, funny, uplifting, entertaining? Are they negative, outrage-inducing, offensive anxiety-provoking? It doesn’t all have to be sunshine and rainbow memes, but the quality of the content you produce and engage with is likely to have an impact on the way you feel. Try asking your teen:

What are some of the best/funniest/most entertaining TikToks you’ve seen recently?

What have you posted recently that you’re proud of? Why?

What are you chatting with Sarah about? How is she doing?

The Who. Now consider who you’re interacting with. Are the people you’re messaging making you feel better or worse? Do your followers seem excited about the things you post—or does the comment section leave you feeling deflated? Are you eager to scroll—or more eager to roll your eyes—when you notice that someone you follow has posted new content? Try asking your teen:

What are some of your favorite accounts to follow to Instagram? Why?

Who usually likes or comments on your TikToks, and who doesn’t? Are you ever surprised by that? What kinds of things do people say?

Who are you talking to on Snapchat these days? Who makes you laugh? Who’s a good listener?

The How. Finally, consider whether there are changes you can make to maximize the benefits of the what and the who of your social media use. What balance of public versus private, and active versus passive, works for you? Maybe you want to do more messaging and less posting. Maybe you want to do less scrolling and more commenting. How can you cultivate an online social circle that makes you feel good? Try asking your teen:

When do you think social media makes you feel better, and when do you think it has no effect, or makes you feel worse? When you feel that way, what kinds of things are you doing, or who are you talking to?

Are there any changes you could make to your social media use that would make it work better for you? What have you tried in the past that has worked?

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

Full citation: Valkenburg, P. M., van Driel, I. I., & Beyens, I. (2021). The associations of active and passive social media use with well-being: A critical scoping review. New Media & Society. https://psyarxiv.com/j6xqz/

It’s worth noting that Patti Valkenburg is not just any scientist. She’s a celebrity in the world of media effects. She’s published over 150 journal articles and 8 (!) books, and even has her own Wikipedia page. Plus, according to her Twitter bio, she’s both a wine connoisseur and 5K runner. Stars—they’re just like us.

According to Emojipedia: 🕴️“This character was originally introduced into the Webdings font as an ‘exclamation mark in the style of the rude boy logo found on records by The Specials.’ This levitating man was known as Walt Jabsco.” I still have literally no idea what this means. Has anyone ever used this emoji? What was the context? I must know.

My favorite aspect of this study—besides the rigorous scientific methodology and meaningful results, of course— is the use of the word “hodgepodge” in the abstract (i.e., “We found 40 survey-based studies, which used a hodgepodge of 36 operationalizations…”). Not a word you see everyday in research studies, but the perfect choice here. Score: 1 for hodgepodge, 0 for the active vs. passive social media use distinction.

This study was what’s called a “scoping review.” The idea here is to identify all the the studies published on a certain topic, in order to “scope” a body of literature—that is, to see what’s out there, what’s missing, and how a topic has been conceptualized. If you’re looking for more info, and a little bit of academic inception, here’s a scoping review of scoping reviews.