Welcome to Techno Sapiens! Subscribe to join thousands of other readers and get research-backed tips for living and parenting in the digital age.

5 min read

When I was in fourth grade, I walked into the stuffy, carpeted classroom one day to find piles of brown paper grocery bags, scissors, and Sharpies lined up on the desks.

We were making lungs.

The instructions were simple: use a stencil to trace the shape of a lung on the brown paper. Cut it out. Then, with a Sharpie, start writing on the lung. The prompt? The Dangers of Smoking Cigarettes1.

As we diligently scrawled words like “CANCER” and “SHORTNESS OF BREATH” in dark black ink, I remember thinking: Is this really necessary? At the time, I was aware of exactly zero people who smoked. The idea that kids my age might be offering me cigarettes was laughable. It was as if adults in my life were obsessed with the dangers of, say, hitchhiking—I recognized that this had once been a very relevant problem for them, but for me, it hadn’t really come up.

Was the lung activity a bit heavy-handed? I’d say so. But it also speaks to a common scenario: as adults, the fears we have for our children are so often projections of our own experiences.

Our perfectly healthy, not-at-all-problematic relationship with Instagram

Fast-forward 25 years. It’s Summer 2022, and Instagram has overhauled its user interface. Full-screen video. More recommended content. Algorithms that prioritize reels over static posts. A general TikTokification2 of the platform.

As adults of a certain age, we lose our collective minds.

Make Instagram Instagram again! We, and our celebrity spokespeople3, cry. Bring back our filtered photos! Bring back our curated content! Bring back our friends’ and closest influencer buddies’ highlight reels! Let us scroll mindlessly for hours through our old feeds!

As we cling to the social media we know and love and have spent the past decade proclaiming is ruining our mental health, our desperation grows. There’s a hunger in our thought pieces and (static) photo captions. Give it back to us!

We plead with our Big Tech overlords that they may grant us our old, familiar photos of friends on expensive vacations and cousins’ unhinged political rants.

And yet, simultaneously, we take up a familiar cause. Think of the children! Our fears for our children reach a fever pitch. Those filtered photos, curated content, highlight reels, mindless scrolling, unhinged political rants…imagine the effect those things have on a person!

Get the kids off social media! we cry. They can’t handle it like we do.

A generation of digital parents

The majority of Millennials (ages 26-41) and Gen-Xers (ages 42-57) use social media, with over 70% of us on Facebook and nearly half of us on Instagram4. Roughly 90% of us have a smartphone.

Facebook opened up to the public in 2006. The first iPhone was released in 2007. This means some of us have been curating profile photos since we were in high school. Many of us have spent the entirety of our parenting years—from the moment our (digital) pregnancy tests showed a positive result—with a social media-wielding smartphone in our pockets.

So, how’s that working out for us?

It’s hard to say.

Many of us benefit from the sense of connection social media provides. We go online for advice, help, and guidance. Social media makes us laugh, entertains us, allows us to share important moments with family and friends.

And yet.

More than half of us (56%) say we spend too much time on our phones, and 68% say we feel distracted by our phones when spending time with our kids.

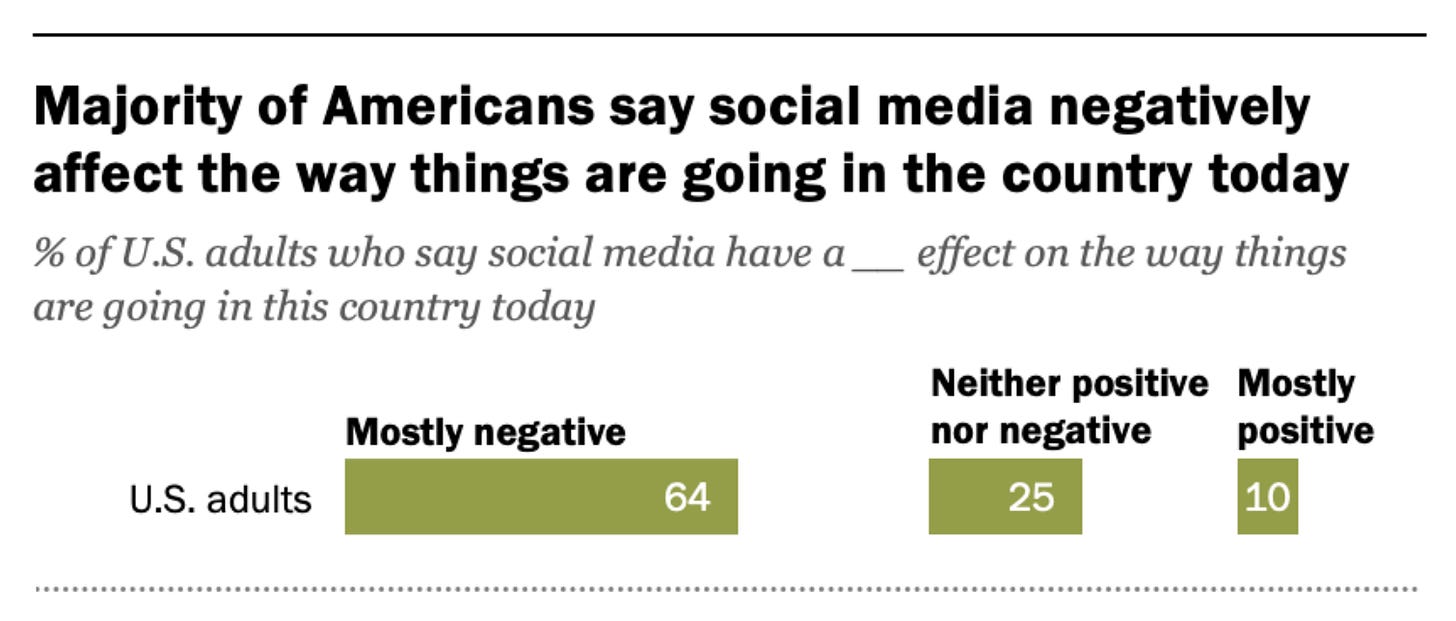

The majority of us (64%) believe that social media has a mostly negative effect on the way things are going in the country.

Nearly half of us (41%) have personally experienced online harassment, ranging from name-calling to physical threats.

Many of us report frequently or sometimes seeing content that makes us feel depressed (49%), or lonely (31%).

It’s no wonder we are fearful for our kids.

As our thumbs slide up over the tips and tricks and sponsored purchasing decisions of parenting influencers—who, it turns out, are just other parents—we worry our children will be influenced by their peers. As we struggle to resist the siren song of notifications and pull-to-refreshes, we worry our children will become distracted. As our eyes gloss over photos of smiling family vacations and newly renovated homes and perfect bodies in perfect outfits that somehow are not covered in the remnants of children’s breakfasts, we worry our children will feel they don’t measure up.

The dangers of screen time

A few weeks ago, I sat at my computer doing what I often do. Reading articles about the potential harms of social media for teens’ mental health. Running analyses examining associations between teens’ social media use and depression. Writing about the effects of social media on teens’ social relationships, emotions, attention spans.

Except five minutes in, I felt a familiar itch in my fingers. With one practiced, fluid motion, I was on Instagram. Distracted. A woman’s face was suddenly staring at mine—perfect lighting, styled hair, tailored athleisure wear signaling “authenticity,” as Instagram has now decreed. A rolling caption appeared over her latest parenting advice video: The Dangers of Screen Time.

Our children have faced, and will continue to face, real problems when it comes to social media. But will those problems mimic ours? Or will filtered photo comparisons and constant distraction go the way of smoking in a 1998 suburban elementary school? Dangerous, of course, but lagging in relevance behind newer, more pressing concerns that our parents never could have predicted.

So often, our fears for our children reflect our own challenges. And when it comes to social media, challenges abound. Perhaps we need a moment to look up from our screens, away from our children, and back toward ourselves.

Perhaps, if we want to help our children develop healthy relationships to social media, we first need to figure out our own.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

In case you missed it

As with any person who attended elementary or middle school in the U.S. in the 80s/90s, I have a number of other memories of anti-drug education. I assume these involved some version of DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education), one of the most widely-used substance abuse prevention programs at the time. One of these memories involves a police officer coming to the classroom with a police dog, and teaching us that it was illegal to grow marijuana. Another involves a contest among fourth and fifth graders to create anti-drug posters, resulting in dozens of homemade “Just Say No!” variations adorning the hallways of the school. One such poster, I remember, involved a handmade drawing of the Spice Girls? Based on these memories, you’ll be surprised to learn that DARE, it turns out, was entirely ineffective.

Instagram, it seems, has reason to be concerned about TikTok. Apparently, Instagram users are spending only (ha) 17.6 million hours a day watching Reels, whereas TikTok users are spending 197.8 million hours watching TikTok videos. The average TikTok user spends 29 hours per month (!!!) on the platform, compared to just 8 hours per month for Instagram.

By “celebrity spokespeople,” I, of course, mean the the Kardashian Jenner family. This summer, after Instagram began rolling out new features in an effort to compete with TikTok, Kylie Jenner posted the following story: “Make Instagram Instagram again. (stop trying to be tiktok i just want to see cute photos of my friends.) Sincerely, everyone.” [see above photo.] Kim Kardashian posted a similar follow-up. I can only imagine the panic that ensued at Instagram.

A note on the percentages in this section, because academia has instilled in me a fear of numbers not reported to the hundredths place. I did my best to present stats for the 26- to 57-year-old age range (Milennials and Gen X). In some cases, this involved downloading Pew’s available data and running my own analyses. In others, it involved estimating based on Pew’s reported age breakdowns (18-29, 30-49, and 50-64). Sometimes, the only numbers available from Pew were for “U.S. adults” or “U.S. parents of a child ages 17 and under”). If, for some reason, you are planning to base any major life decisions on these percentages, please refer to Pew’s original reports and available data for a more detailed breakdown.