New Study: A "vaccine" for misinformation

Can a new technique called prebunking reduce our susceptibility to online misinformation?

Hi there, techno sapiens! We’re back with another edition of Techno Research, where I break down the findings of a newly published study on psychology, tech, and/or parenting.

But first, a brief programming note. A few footnote-enthusiast sapiens1 have requested clickable footnotes, i.e., where you click the number in the main text to take you to the footnote, and then click the number in the footnote to take you back up to the main text. As it currently stands, this feature is only available when reading posts in the browser. I’ve reached out to the Substack powers-that-be to request this feature in email, but in the meantime, I suggest reading posts in your browser, where my beloved footnotes are all linked in-text. Thanks for reading, thanks for the feedback, and thank God for footnotes.

Summary for Busy Sapiens

New study2 aims to reduce our susceptibility to online misinformation

Researchers created five short videos to “inoculate” people against manipulation techniques commonly used in misinformation

Participants who watched the videos were better able to recognize manipulative social media posts and less willing to share them

Researchers tested the videos in experiments with 6,484 U.S. adults. Then, they showed the videos as YouTube ads, reaching 5.4 million users.

6 minute read

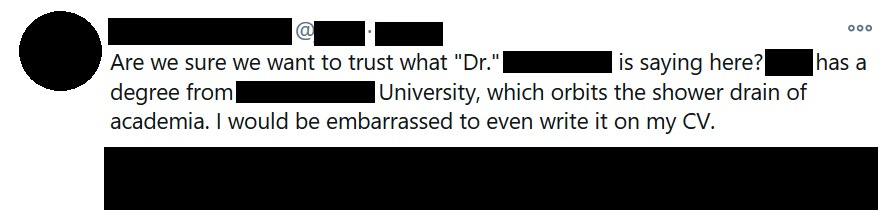

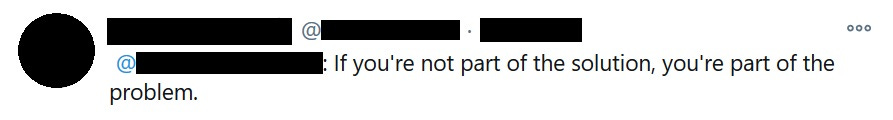

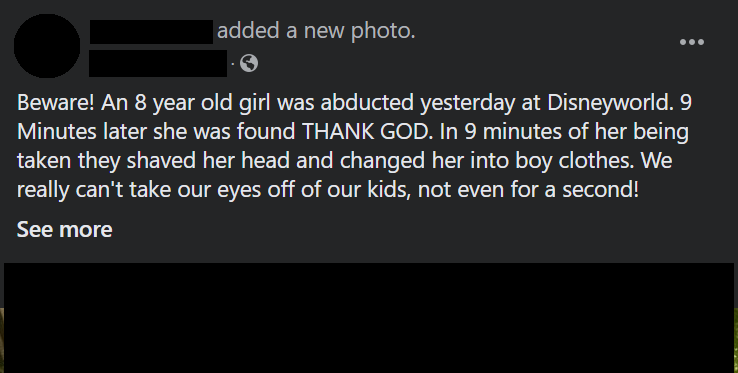

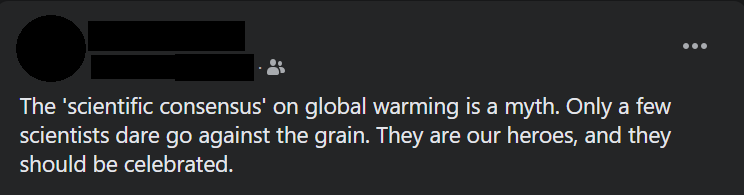

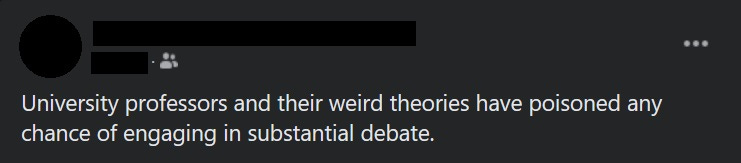

Take a look at the following social media posts. What do they have in common?

Yes, true, lots of unnecessary negativity toward “scientists” and “University professors.” Let’s just ignore that for now.

What else do they have in common?

All of these posts include manipulation techniques used to spread online misinformation. They’re designed to trick us—to make us believe things that aren’t true—by playing on our emotions or presenting faulty reasoning.

Misinformation, or incorrect information presented as fact, is common on social media, from TikToks claiming the earth is flat (it is not) to YouTube videos warning that birds aren’t real3 (they are). And it has a major impact on our lives—not just online, but offline, too—from vaccine hesitancy to political elections to parenting.

Scientists have tried lots of strategies for combating online misinformation. But strategies that aim to correct, retract, or “fact-check” information after it’s been shared can backfire. When evidence is presented that counteracts a person’s worldview, for example, it can actually strengthen previously held (mistaken) beliefs. And even when we retract misinformation, it often fails to correct people’s beliefs—something called the continued influence effect.

That’s where today’s study, led by Jon Roozenbeek at the University of Cambridge, comes in. The scientists test a new strategy: rather than debunking misinformation, they “prebunk” it. In the same way a vaccine inoculates us against disease, the researchers tested a new strategy for “inoculating” people against misinformation—and then tried it out on millions of people.

Let’s find out how they did it.

What do you mean “inoculating” people?

The researchers created 5 short “inoculation” videos, each explaining and refuting a different manipulation technique commonly used to spread misinformation. The idea was that, after watching these videos, people would be better prepared to spot misinformation, and subsequently less likely to spread it.

You can watch all of the videos here, but to get a quick flavor, here’s one describing a manipulation technique called Emotional Reasoning:

Now, let’s walk through all five manipulation techniques that the researchers address in the videos, with examples taken directly from the study. This will not only teach us about the study, but also help us inoculate ourselves against online misinformation. Killing two birds with one stone!4

1. Emotional Reasoning

The use of strong emotional words, usually negative ones that evoke fear or anger, that encourage us to pay attention to (and share) online content, regardless of whether it is accurate.

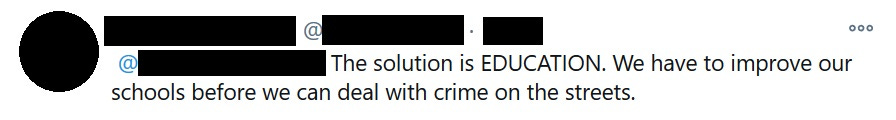

2. False Dichotomy

Also called the “either-or” fallacy, this is when two alternatives are presented as the only possible choices, when really, more options (or both options) are possible. Usually, one alternative is clearly a bad option and is presented in contrast to the alternative that the manipulator wants you to pick.

3. Incoherence

Two or more arguments, which cannot both be true at the same time, are both presented to make a point.

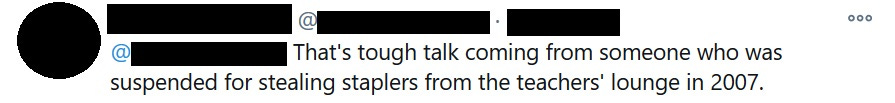

4. Ad Hominem Attack

The person making an argument is attacked, instead of the content of the argument itself. [Also known as: Twitter].

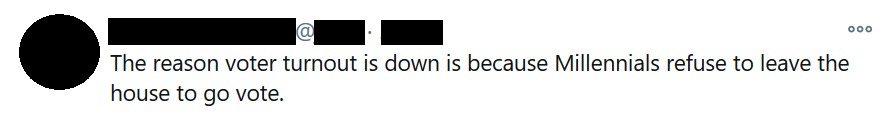

5. Scapegoating

A large or complex problem is blamed entirely on a single individual or group, who cannot reasonably be responsible for it.

Want to check your understanding? Scroll back up to the examples at the beginning of this post and try to spot the manipulation techniques. Answers in the footnotes.5

What did the researchers do with these videos?

They conducted seven (!) different studies.

For Studies 1-6:

They gathered a nationally-representative online sample of 6,484 U.S. adults total.

In each study, they randomly assigned some participants to watch one of the inoculation videos and others (the control group) to watch an unrelated video about freezer burn6.

Then, they showed both groups a series of fake social media posts, including those listed above. Some of these posts contained manipulation techniques, and some did not. (An example of a neutral post: “Education is an important component of our efforts to combat crime on the streets.”)

For each fake post, they asked the participants to identify the manipulation technique (if present) and how confident they were in their choice, rate how trustworthy they found the post, and indicate whether they would share the post on social media.

For Study 7:

They took their findings to the big leagues. They picked two promising inoculation videos (Emotional Reasoning and False Dichotomies) and ran them as YouTube ads—reaching 5.4 million users.

Within 24 hours of watching an inoculation video, a random sample of users (11,432 of them) were asked, again via YouTube, to identify the manipulation technique used in a fake social media post.

A control group of 11,200 people who hadn’t watched the inoculation videos were asked to do the same.

And what did they find?

The videos worked.

For studies 1-6, participants who watched the inoculation videos (compared to those who watched the neutral freezer burn video) were better able to discern between the fake social media posts containing manipulation techniques and those that did not. They were better able to recognize each manipulation technique, and in the cases of Emotional Language, False Dichotomies, and Scapegoating, reported being less likely to share the manipulative post.

The researchers also tested whether these effects held for all participants. They found that the inoculation videos were effective for participants no matter their age, education, political ideology, conspiracy beliefs, or (my personal favorite) “bullshit receptivity.”

For study 7, they found that users who watched the inoculation videos were better able to recognize manipulation techniques in the fake social media posts, compared to users who had not watched the videos. The improvement in detection accuracy was 5% on average. This might not seem like a lot, but if you consider the fact that YouTube has 2.6 billion monthly active users, even small improvements like this can quickly scale into big effects.

What does this all mean?

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: we can only learn so much from a single study. No study is perfect, and this one has its limitations.7 But it’s hard to argue with the fact that this study was rigorous. Tens of thousands of participants. Six controlled experiments and a field study. Pre-registered hypotheses8. High-quality stimuli, sound theoretical rationale, and, to top it all off, fun videos with Family Guy and Star Wars references. The whole package!

To me, the most exciting takeaway of this study is the potential implications. Online misinformation has real, problematic outcomes for adults and kids alike. I worry about the inaccurate information our kids are absorbing about current events, about mental and physical health, and about the world around them. Our previous efforts to combat misinformation have often backfired. So, the idea of inoculating people against it—in short, scalable videos like these—is powerful.

We can imagine a scenario where huge swaths of the population receive interventions like these through ads they were already watching. Where our kids learn to spot these manipulation techniques before they encounter them on TikTok. Where we all get a little bit better at spotting misinformation, and in doing so, slow down its spread.

As for me, this study’s already changed the way I think about my Instagram and Twitter feeds. It’s reminded me of how insidious misinformation can be. Going through the above examples, I knew they were designed to be manipulative. And yet, I still found myself falling prey to some of the fake social media posts.

It’s hard to evaluate this type of content rationally, especially when it conflicts with our worldviews. [What was that comment about University professors, again? What exactly did they mean by weird theories?]

Going forward, I hope I’ll be a little bit more aware.

A quick survey

What did you think of this week’s Techno Sapiens? Your feedback helps me make this better. Thanks!

The Best | Great | Good | Meh | The Worst

In case you missed it

Last point about footnotes (in a footnote, of course): I try to write the footnotes so that they stand on their own, with clear references to the main text in the footnotes themselves. This way—should this be your footnote-reading preference—you can simply read them all at the end, after you’ve finished the main text. I have also heard from some true footnote enthusiasts that they scroll to the bottom of the email to read the footnotes first. Choose your own adventure, techno sapiens!

All example social media posts were taken directly from the open source materials for this study, available here. Full citation: Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., Goldberg, B., Rathje, S., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media. Science advances.

For those unfamiliar, there is, in fact, a conspiracy theory known as the Birds Aren’t Real movement. It claims that our so-called avian friends are actually government-issues drones.

A friend once shared with me this list of animal-friendly idioms, written by PETA to replace phrases thought to promote violence toward animals. I can no longer use the phrase “killing two birds with one stone” without silently mouthing to myself “feeding two birds with one scone.” Some other favorites: “put all your berries in one bowl” instead of “put all your eggs in one basket”; “feed a fed horse” instead of “beat a dead horse”; and, of course, “bring home the bagels” instead of “bring home the bacon.”

Answers to example social media posts: #1 - Ad Hominem; #2 - False Dichotomy; #3 - Emotional Reasoning; #4 - Incoherence; #5 - Scapegoating

Incidentally, I recently returned from vacation to find that a number of items in my freezer were coated with a thin layer of ice flakes, so I was equally excited by the educational control video about freezer burn as I was by the inoculation videos. Learning to stop the spread of misinformation and freezer burn? This study was everything I didn’t know I needed this week.

Some limitations of the current study: the effect sizes were small and short-term, we don’t know whether the inoculation videos changed participants’ actual behavior, and the Incoherence and Scapegoating videos seemed less effective than the others. The latter may be because people were already pretty good at spotting these techniques before watching the videos, so there was less change in their ability to detect them.

In recent years, there’s been a movement toward “open science” in academia. The basic idea is that the quality of science will improve if we’re more transparent about our methods. One component of the open science movement is “pre-registering” hypotheses. Here’s how it works: scientists log into a central database like this one, describe the study they plan to conduct, and then state, in advance, what they expect to find. That way, when the study is over, they can’t take a look at their significant results and retroactively claim that they fit with their hypotheses. There is much debate about the merits of this process but, in general, studies that have been “pre-registered” are often considered more rigorous.

I find four of your five examples are incorrect. The examples you provide for Emotional Reasoning, False Dichotomy, Incoherence and Scapegoating are not examples by your own definitions provided. I also note that emotional reasoning is not the term the provided video uses to describe the phenomenon described, which is good, because emotional reasoning is something else entirely. I am copying my critiques from a comment on another blog discussing your points.

Emotional Reasoning: "Baby formula linked to horrific outbreak of new, terrifying disease among helpless infants. Parents despair." - Sure, that's a lot of scary language to cram into a headline, but no argument is being made. No facts are being replaced by emotion in a process of reasoning. Click baity, but not emotional reasoning (which is what the video suggests, to be fair; they don't call it emotional reasoning either.)

False Dichotomy: "The solution is EDUCATION. We have to improve our schools before we can deal with crime on the streets." So... where is the dichotomy here? There is no "Either you do X, or you do Y" choice, but rather a statement of steps and the order to take them in. You can argue that it is false that you have to fix the schools before dealing with crime, but the argument (or perhaps just the point) is that crime is solved by education. No dichotomy.

Incoherence: "You don't know what you're talking about. Even though science is yet to show a correlation, it's very clear that violent video games like ___ make people more likely to commit crimes." Those can both be true at the same point (although they are not arguments like she says, but statements of fact as perceived by the arguer). Science has yet to show that I have three kids, but I clearly do; I am still awaiting a response from the publisher on the study I submitted, but you know how peer review goes.

5: Scapegoating: "The reason voter turnout is down is because Millennials refuse to leave the house to go vote." She defines scapegoating as "A large or complex problem is blamed entirely on a single individual or group, who cannot reasonably be responsible for it." Is it unreasonable that voter turnout is down because a slice of eligible voters doesn't want to get out and vote? Really? Now, one would want to see some numbers on that, like voting % of each age bracketed generation over time, showing that other cohorts vote at pretty much the same rate as always but Millennials are really low and bring the overall average down, but it is a reasonable claim, and one that can be falsified. Whether or not it is because they refuse to leave the house to go vote, or refuse to leave the house in general, or are fine leaving the house but refuse to wait in line to vote, that's a different question, and might not be testable.