When does screen time become a problem?

Plus: new research on social media and teen mental health

Welcome back, sapiens!

Here in the Northeastern U.S., yesterday was both the end of Daylight Saving Time and, according to research conducted in my own home, the longest parenting day of the calendar year. As the sun began setting at 4:30pm, my husband and I looked at each other in a panic, stuffed animals flying in the air behind us and the wreckage of play-dough spread out on the table before us. Please, sapiens, send along your best ideas for entertaining toddlers when it’s dark outside. It’s going to be a long four months.

On a lighter (!) note, it’s time for a brand new, hot-off-the-presses research roundup!

Last time, we discussed the latest research on how TikTok may increase boredom, whether tablets make kids angry, and why parents think life is harder for teens today.

Today we’ve got new studies on:

Social media and teen mental health

Problematic screen use in young kids

What videos kids are seeing on YouTube

Reminder: to support Techno Sapiens and get full access to monthly research roundups like this one, please consider a paid subscription (20% off right now!)

1. Are we doing research on social media and youth mental health all wrong?

The debate about social media and teen mental health has taken many twists and turns in recent weeks. (See, for example: this live debate between Jonathan Haidt and Candice Odgers, this article about the controversy over a recent meta-analysis, and this Wall Street Journal article, in which I make a brief appearance).1

This study offers something a bit different. Here’s what the researchers did:

They start with a common theory: “social media use is the primary cause of the decline in youth mental health, especially for girls.”

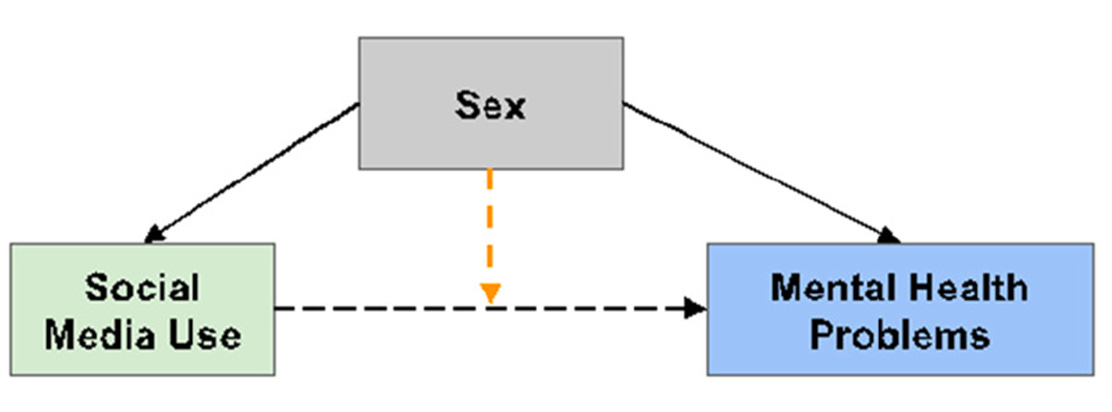

They turn that theory into an actual statistical model. It looks like this:

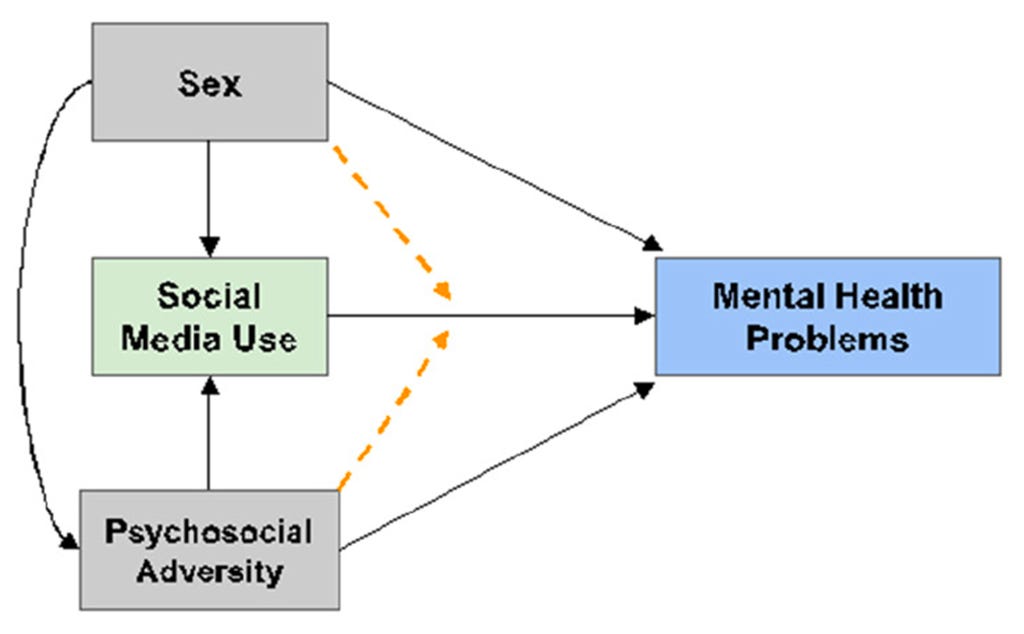

Now, they create another model, where other potential causes of mental health problems are also included. They lump these all together into a category called “psychosocial adversity,” but this could include everything from trauma to discrimination to low self-esteem. It looks like this:

Now the fun part. They ask: What would happen if the actual effect of social media use on mental health problems was zero, but the effect of all the other bad stuff was more than zero? If we failed to include psychosocial adversity in our models, or if we only partially accounted for it, what would happen?

To answer this, they “simulate” (i.e., make up) data, where the effect of social media use is, in fact, zero, and the effect of psychosocial adversity is more than zero. They run some tests.

And the kicker: when psychosocial adversity is not properly accounted for, the results make it look like the effect of social media is significant, even when it is actually (by design) zero.

In sum, if we fail to adequately account for the many factors that can influence, and be influenced by, social media use and mental health, we may mistakenly see relationships between them that are nothing more than statistical artifacts.

My take: Phew! To be honest, I saw this study a while ago, but it took me some time to make sure I could convey it as simply and accurately as possible. This speaks to a larger problem in this debate. It’s a lot easier to understand “social media causes depression in teen girls” than it is to understand, as this paper states, “the implicit data-generating process (i.e. the theoretical framework and set of mechanisms through which observed data are produced) assumed…neglects the confounding role of chronic or acute psychosocial adversity.” These issues are complicated, and we have to be willing to sort through that complexity if we want to get it right. J of Psych and Clin Sci. [Alternatively, check out this tweet thread by first author Craig Sewall, from which the paper originated].

For more on this, check out: Techno Sapiens Ultimate Guide to Teens, Phones, and Mental Health and Making Sense of The Anxious Generation.

2. When do screens become a problem for little kids?

We often hear discussion of screen “addiction,” but because researchers disagree about how excessive screen use should be classified, they prefer a different term: Problematic Media Use. A few years ago, researchers developed a parent-reported measure of Problematic Media Use for kids ages 4-11. More recently, researchers found that this measure could be used with parents of even younger kids.

Now, a new study assesses Problematic Media Use (PMU) among 269 children, following them from ages 2.5 to 5.5.