Welcome to Techno Sapiens! I’m Jacqueline Nesi, a psychologist and professor at Brown University, co-founder of Tech Without Stress (@techwithoutstress), and mom of two young kids.

Happy Monday, sapiens!

We’re trying something new today, and I’m very excited about it: our very first, state-of-the-art, all-in-one, everything-you-ever-needed-to-know, (lots-of-hyphenated-words) Techno Sapiens Ultimate Guide.

In this Ultimate Guide, I’m answering your most frequently asked questions about teens, phones, and social media. I’m pulling together all the writing I’ve done on this topic over the past 2+ years and summarizing it, along with new insights and commentary. My hope is that this guide can act as a one-stop-shop for understanding the science and getting practical advice on these issues, so you can easily access the answers you need, all in one place.

Note: this guide is, by design, on the longer side. If you don’t have time to read it at this moment (I get it!), it will be bookmarked on the Techno Sapiens website. Stop by anytime and peruse at your leisure.

Here’s what’s covered in this guide:

Did social media cause the teen mental health crisis?

What are the real risks (and benefits) of phones and social media?

What should we (as a society) do about this?

How will phones and social media impact my teen?

How much are teens actually using smartphones and social media?

Is social media “addicting?” What role does dopamine play?

I’ve heard the APA and Surgeon General make statements about social media—what should I make of those?

How about smartphones? What’s the right age for my kid to get one?

Are there alternatives to smartphones for kids?

How do I set boundaries around phone use for my child?

How closely should I monitor my child’s phone?

Other relevant information

1. Did social media cause the teen mental health crisis?

Let’s start here.

As a clinical psychologist and researcher, I’ve been studying the effects of smartphones and social media on teen mental health for 12+ years. Here’s the short answer, from this (very detailed, aptly named) post: Did social media cause the teen mental health crisis?:

I think there is a very good chance (my current number is probably around 75%) that social media has contributed to the teen mental health crisis. At the same time, I think large-scale mental health crises are complex phenomena, that there are likely multiple causes, and that we need to make sure we’re approaching the data with the scrutiny it deserves. It’s this nuance that, I think, has been missing from the conversation.

We have some empirical evidence that social media plays a role in the teen mental health epidemic. We also have common sense, which suggests that this is a reasonable hypothesis. However, we also have a fair amount of data that does not fit with this nice, clean narrative. For more, see the aforementioned post, this shorter summary of the issue (with

), and this analysis of the current state of the research.Ultimately, I worry that by embracing social media as the (single, definitive) cause of the mental health crisis, we’ll forget to address the many other factors crucial to supporting teens’ mental health. In short: we need to fix the social media problem, but we need to do other stuff, too. And we need a lot more research to figure out exactly how, when, and why social media is (or is not) involved.

2. What are the real risks (and benefits) of phones and social media?

There are many potential risks, but we can break them down into two major categories.

The first is overuse, or teens using these technologies so much that they interfere with other activities that are important for their well-being (e.g., sleep, physical activity, in-person time with friends).

The second is harmful experiences, or exposure to things they shouldn’t be seeing (e.g., problematic mental health content) or doing (e.g., obsessing over ‘likes’).

Potential benefits include: staying connected to friends, meeting like-minded peers, learning, and discovery. This may be especially true for teens who might feel marginalized in their “offline” lives, like LGBTQ+ teens (though, these teens are also more likely to encounter risks online).

Now, how should we think about weighing these risks and benefits? I wrote about that in this post on how to think about this research:

As it currently stands, social media platforms are not designed with the right balance of risks and benefits in mind. Yes, there’s plenty of good stuff. But if you were starting from scratch, designing a product that you were confident would do a great job of providing all those benefits (social connection, fun, learning) while minimizing the downsides, would you come up with TikTok? No.

And with social media apps designed as they currently are, is it, in general, a good thing for teens to be spending 3 hours everyday scrolling TikTok?

Also, probably no.

3. What should we (as a society) do about this?

Here’s where we venture into the realm of legislation. Many states have now introduced or passed laws targeting youth social media use, and there are a number of federal proposals aiming to do the same.

I’ve written before that, in many ways, the ongoing debate about social media as a cause of mental health issues has become a distraction. The science will likely never be 100% definitive on this, but that doesn’t mean we can’t do anything about it. When Big Tech CEO’s testified before congress and re-ignited the debate, I wrote:

The evidence on the relationship between social media use and mental health is complicated. We know this! If the question we’re asking is: “Is social media causing adolescent mental health problems?” the answer right now is: it depends. I firmly believe this is a critical question, and one we need to continue working to understand. But here’s the thing: we don’t need to answer that question to start fixing things. We can begin by answering a much simpler question: “Should tech companies make changes to their products to protect children’s safety and well-being?” The answer to that? A resounding yes.

A number of states (41, to be exact) have also joined together in a lawsuit against Meta for violating consumer protection laws and harming young users. As I wrote here:

Some of the claims made in the lawsuit are defensible from a research standpoint, and some are not. Ultimately, it’s clear that we need to do a better job of protecting young people online, but I think we can do this without overstating the available evidence.

I continue to believe that we need to do a better job protecting young people online, and although we do need more research to answer lots of different questions around this issue, we don’t need more research to tell us whether to act.

The question is: how?

Some proposals are aiming to ban social media use altogether among users below a certain age (e.g., 16).

Others are aiming to remove certain features of social media platforms (like endless scroll and auto-play) to make them safer.

I see merit in both ideas, here, and in many ways, I think the reasoning becomes circular. If we remove so many features of social media platforms for teens that they end up resembling simple messaging platforms, we’ve effectively banned “social media” as we currently conceive of it.

4. How will phones and social media impact my teen?

One of the key findings in studies that look at connections between social media use and teen mental health is that the effects really depend on (a) how teens use it and (b) who they are. We can likely conclude from our own online experiences that an hour spent texting our best friend will have different effects on our well-being than an hour spent comparing ourselves to a fitness influencer’s photos. My own research suggests that kids also respond to social media very differently. Two kids can have the same experience online and one may feel devastated, while another will shrug it off.

It’s really difficult to know how an individual kid will respond to using a smartphone or social media, but here are some things to think about, from an interview I did with Emily Oster:

Okay, so which kids are more likely to be negatively affected by social media? The short answer is that kids who are struggling offline are more likely to be the ones to struggle online. Let’s think about this in categories: social, behavioral, and emotional.

Socially, teens who are struggling — whether that’s getting bullied, being left out or excluded, getting sucked into social “drama” — tend to see more negative effects with social media. The vast majority of kids who are getting bullied on social media are also getting bullied in person. The problem is that, on social media, bullying can be constant, more difficult to escape, more public. So social media may exacerbate the problem for these kids.

Behaviorally, teens who are taking more risks offline, engaging in unsafe behaviors, getting into trouble: these are going to be kids who are more likely to find themselves in risky situations online, like posting photos of drinking alcohol, for example.

Teens who are having emotional difficulties are also more likely to struggle on social media. This includes teens who are particularly invested — even more so than the average teen — in what other kids think of them, or in what they look like in photos or how they “stack up” to their peers. Compared with boys, girls tend to be more highly invested in their social media use, and many studies do show more negative effects for girls. I’d also include in this category teens who are struggling with their mental health. One nationally representative survey, for example, finds that teens with depressive symptoms (vs. teens without) are more likely to say they often compare themselves negatively to others online.

5. How much are teens using smartphones and social media?

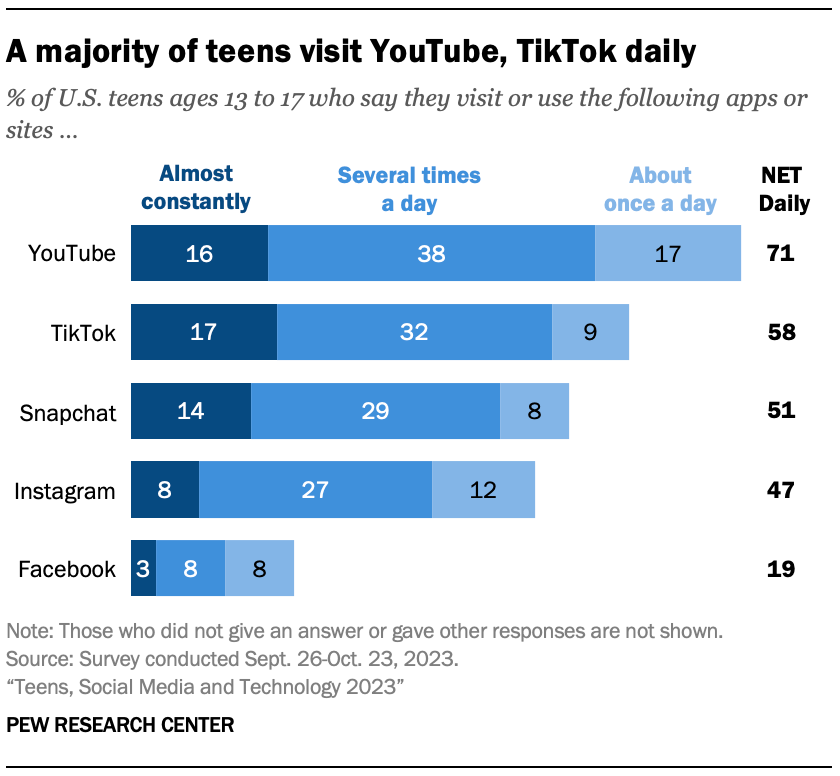

The most recent, comprehensive data we have on this in the U.S. comes from the Pew Research Center, and the short answer is: a lot! Here’s my full summary of the Pew data. But in short, as of late 2023:

95% of teens ages 13-17 have a smartphone. This is “nearly universal,” and does not differ significantly based on gender, age, race and ethnicity, or household income

Nearly all of teens (93%) use YouTube, with TikTok (63%), Snapchat (60%), and Instagram (59%) roughly tied for second place

One-third of teens are using one of the top five sites “almost constantly”

And here’s a summary of a large 2023 study I did with Common Sense Media, focused on girls ages 11-15. The results generally line up, and, interestingly, we find that more girls report these platforms have had a mostly positive (versus mostly negative) impact on people their age.

6. Is social media “addicting?” Should we blame it on dopamine?

We know that social media platforms were designed with elements—e.g., endless scroll, notifications, autoplay—that make kids more likely to use them excessively. Dopamine is likely involved here, but that doesn’t necessarily equate to “addiction.” As I wrote in this post (Kids, screens and dopamine):

Dopamine almost certainly plays a role in kids’ screen use, but so do many other chemicals and systems in the brain. These chemicals and systems (including dopamine) also play a role in lots of other activities, from getting hugs to eating snacks. Just because dopamine is involved does not mean screens are dangerous or toxic. Dopamine is not a cause for panic. It’s just…how the brain works.

At the same time, a small percentage of kids do use technology in ways that are problematic and highly interfering, and which might be classified as an “addiction,” and dopamine is involved here, too. Plus, some types of screen use (e.g., social media) are designed to be highly rewarding and hard to stop. Technologies targeted to kids should not be designed this way.

There are certainly some kids (and adults) who use social media in ways that are highly problematic, but there is considerable debate about whether this should be termed “addiction.” There is currently no official diagnosis of “social media addiction.” I lay out some of the challenges with labeling “social media addiction” in this post:

Studies of “social media addiction” have often adapted the criteria for other addictions [e.g., find it difficult to resist using it, feeling distressed when unable to access it] to apply to social media, instead.

This seems logical, of course. Why not take what we know from another problematic behavior and just apply it to social media? Well, the current study lays bare the limitations of that approach. It turns out, it’s easy to show that a behavior is “pathological” when we go in with assumptions about that behavior….

Does this mean that there is no such thing as problematic or even "addictive" social media use? In my mind, no…What it does mean is that we need to be careful in how we assess, talk about, and label issues of social media “addiction.”

7. I’ve heard the APA and Surgeon General make statements about social media—what should I make of those?

I contributed to the American Psychological Association’s Health Advisory on Social Media Use in Adolescence, which offers 10 recommendations for parents, tech companies, educators, policy-makers, and more. These include:

Social media should be age-appropriate

Social media should not interfere with kids’ sleep and physical activity

Social media use should be preceded by training in social media literacy.

These recommendations provide a good, basic overview of what we know kids need online. I summarized them here.

The Surgeon General also has an advisory on social media use and youth mental health. As I wrote:

I agree with much of what’s stated in the advisory, including that, at this time, it’s difficult to draw firm conclusions about the role of social media in youth mental health. As the advisory states, social media has both risks and benefits, its influence on mental health depends on how it’s used, it has different effects on different kids, and there are many remaining questions and gaps in the research evidence. Even so, it makes sense to be cautious—to take a “safety-first” approach. The toy comparison [i.e., we should approach regulating social media companies the way we do with children’s toys] is a good one. No matter what the overall evidence has to say about the well-being impacts of toys, it makes sense to take precautions due to potential risks of harm (as long as those precautions don’t do more harm than good).

8. How about smartphones? What’s the right age for my kid to get one?

You’ll be unsurprised to learn that there is no one, specific “right” age for a child to get a smartphone. As I said in an interview with Melinda Wenner Moyer (When Should Your Kid Get a Phone?):

I think the question of when a kid should get a phone is so tricky, because it's both really personal — it's dependent on the kid, and dependent on the family and their values and lifestyles. But it's also really tough to ignore some of the external pressures. Other kids their age are getting phones. Maybe the schools are starting to ask kids to do things that require that they have their own devices. This is actually a really tough issue. And like everything in parenting, there really isn't one single right answer.

That said, I do think that it makes sense to try to wait on a smartphone when possible. We have some evidence that smartphones interfere with social interactions. I wrote about this recent experiment (New study: A better way to kill time), for example, in which students assigned to spend time in a waiting room without phones reported more socialization and better mood than those who waited with their phones.

We also have some evidence that phones can cause distraction and interfere with academic performance—which is, in my opinion, somewhat common sense. Any evidence on a specific, correct age for smartphone introduction is, at best, correlational (see That new study about kids and smartphones). Note: we do have some evidence that social media can be more harmful for younger, versus older, adolescents (see New study on kids and social media).

So, when might your child be ready? One way to think about this is that our kids should understand “4 R’s” before they get a smartphone (as I discuss in-depth here):

Responsibility - Do they know what it means to be responsible with a phone?

Rules - Do they understand the rules around phone use?

Risks - Do they understand the potential risks of a phone and what to do if they encounter them?

Reasons - What are their reasons for wanting a phone?

9. Are there alternatives to smartphones for kids?

Yes! You’ve got options!

Option #1: A basic phone (e.g., flip phone)

Option #2: A “minimalist” or kid-friendly smartphone (e.g., Gabb, Pinwheel, or Bark phone)

Option #3: A smartwatch

Here’s a detailed list of phone alternatives, with pros and cons. And here are some smartwatch considerations.

10. How do I set boundaries around phone use for my child?

First: consider what rules and limits you’d like to have in place. Here’s a list to get you started (from this Q&A: Rules for smartphones):

No phone in the bedroom, especially at night. Sleep is essential. Most teens don’t get enough of it. Phones get in the way.

At least one other phone-free location or time of day. Family meals, car rides, while they’re sitting on the couch, whatever. (You’ll need to stick to this one, too).

Get permission before downloading new apps or making purchases. You can also set this up via parental controls. This helps you stay on top of the apps they’re using.

Use good judgment. This one’s a little squishy, and can be tailored to your family’s values, but in addition to “here’s what not to do” rules (like those listed above), you’ll also probably want a “here’s what to do” rule. This might cover things like: be kind to others online, focus on consuming positive content, and think before sending/posting things publicly.

Respond to you when you text or call them. This one’s about digital etiquette…and also about preventing you from losing your mind.

It also makes sense, especially for younger teens, to have some kind of parental controls in place. But as I wrote in this post (Quick guide to parental controls):

When it comes to parental controls, the bottom line is this: they are a gate, not a wall. They can be useful and important for slowing kids down, for putting a barrier where one should exist. But they are rarely foolproof. Kids can get around them. Just like with gates, they’re unfortunately not a set-it-and-forget-it solution.

With that in mind, this post describes available options for parental controls on: TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, iPhones/iPads, and Android devices. Note that available options and default settings are always changing (e.g., see recent Meta policy updates on mental health content for kids).

Finally, you’ll want any kind of rules or boundaries to fit within your larger system of “discipline”—by which I mean thinking about how we build positive relationships with our kids, create structure, and respond to their behavior. Here’s a detailed guide on discipline and how to think about consequences (e.g, should you take their phone away as a punishment?)

11. How closely should I monitor my child’s phone?

Everything you need to know is in this post (Should your read your kid’s texts?)

The summary:

There’s no data to suggest that reading your child’s text messages is something you need to do.

There’s also no data to suggest that doing so—when communicated in advance and paired with other, age-appropriate tech parenting strategies—is something you shouldn’t do.

Whether to monitor your child’s device will depend on your preferences, as well as your child’s age, history, and tech access

I’ve also got a handy script in there to give you some ideas on what to say to your child about this.

12. Other relevant information

The problem with depression memes.

The promise and pitfalls of self-diagnosis on social media

What is social media literacy? Does your child have it?

Research-backed tips for raising healthy, happy teens

The problem with mental health awareness

Tech Without Stress: My online parenting course (with Dr. Emily Weinstein) for parents of pre-teens and teens.

What did you think?

I’m always trying to make Techno Sapiens better, and I want your feedback! What did you think of this Ultimate Guide? Suggestions? Ideas? Thank you!

We have a 14 and an 8 year old. The 8 year old does not have a phone, or tablet, the 14 year does. We live in Greece, where the school system is very centralised and old fashioned. Schools aren't great, but I see it as a great advantage that they don't use modern technology, just books. Phone use at the older one's school has become an epidemic in the eyes of the school, and I can understand that. The reasons are complex and not necessarily related to phones, but I think it is good idea to ban them at school all together. If there is an emergency, you can always call the school.

On the whole, I agree with what is written here. Personally I am even a bit more on the cautious side - we don't need the ultimate evidence or crystal clear clinical definitions to see the addictive potential of phone use. And it doesn't really matter which chemicals are involved. But then, reality dictates what we can do anyway, and radical solutions won't work when they simply exclude our kids from the life out there.

Such great content. Our son's high school at the first parent event in the Fall said "Parents - please don't text your kids while they are at school. We have students who tell us they have to keep their phones one because their parents want to be able to reach them. Your kids are at school. Let them be here. Let them concentrate. If something urgent or important comes up, we'll reach out to you. We promise."